This 12-year-old is designing a new way to detect tornados

When Anirudh Rao was 4 years old and living in Nashville, his friend’s house was destroyed by a tornado. A year later—yes, as a kindergartner—Rao started sketching a potential solution for better tornado warnings. Now 12 years old and living in Colorado, Rao is pursuing a more advanced version of his concept: a network of drones that could theoretically sense infrasound, a wave phenomenon emitted before and during tornadoes with frequencies below the threshold of human hearing. “On the outskirts of the city, there’ll be a base station and a network of autonomous drones that fly in all directions,” says Rao. He envisions sensors detecting infrasound along with temperature, pressure, and altitude, and sending data back to the base station; if a tornado is detected, that information could go to local authorities to trigger an official tornado warning and push notifications on phones. [Photo: courtesy Anirudh Rao/Young Planet Leaders] Currently tornadoes are detected as they have been for decades: through radar and by storm chasers visually spotting them on the ground. But radar doesn’t work perfectly. As storms have started to move east out of the traditional “Tornado Alley” in the center of the country (a trend that may be happening because of climate change), they’re also moving into hillier topography, where radar is even less reliable. As tornadoes are shifting eastward, they’re also reaching more populated areas, increasing the risk. [Photo: courtesy Anirudh Rao/Young Planet Leaders] Rao’s instinct to use infrasound is in line with the latest science. The idea isn’t new, though until tornado patterns changed, radar had been considered good enough. “As tornadoes move into hillier areas and it limits the effectiveness of radar [science is] refocusing on the potential use of infrasound,” says Brian Elbing, a mechanical and aerospace engineering professor at Oklahoma State University. Though it still isn’t fully understood how tornadoes produce infrasound, “you can pick up the signal before the tornado touches the ground, and it lasts the life of the tornado,” Elbing says. “And it carries information about the strength of the tornado.” [Photo: courtesy Anirudh Rao/Young Planet Leaders] Rao’s theory is that rather than building large stationary sensors for infrasound, drones could cover more ground. “My bigger idea was to use the fact that infrasound produced by tornadoes travels hundreds of miles,” he says. “Instead of waiting for it to come closer and then detect it using Doppler [radar], drones can fly outwards in all directions to offer an opportunity to reach out to a potential tornado, thus reducing the detection time and increasing the warning time.” (He calls his concept Revere, named after Paul Revere’s warning during the Revolutionary War.) There are challenges, including the fact that the noise from wind interferes with the sensors that detect infrasound. Rao argues that it’s possible to physically shield the sensor and then filter the signal. Altitude is another challenge, since the pressure would change as the drone flies, but Rao thinks that’s also surmountable. Ebling believes that a stationary network of sensors measuring infrasound is more likely. It would be cheaper to use than radar, and more accurate, so people could feel more confident that a warning wasn’t a false alarm. As the science advances, he says it could be feasible to build commercial networks of sensors as soon as a decade from now. Rao, meanwhile, is continuing to pursue his idea, while also working on an array of other inventions, from a sensor that could measure moisture in wounds to help avoid infection to a biomimetic surface for roads that could help ice melt faster. “I’m really interested in science, and I believe science can solve a lot of problems,” says Rao, who is a National STEM champion and was recently honored by a platform called Young Planet Leaders.

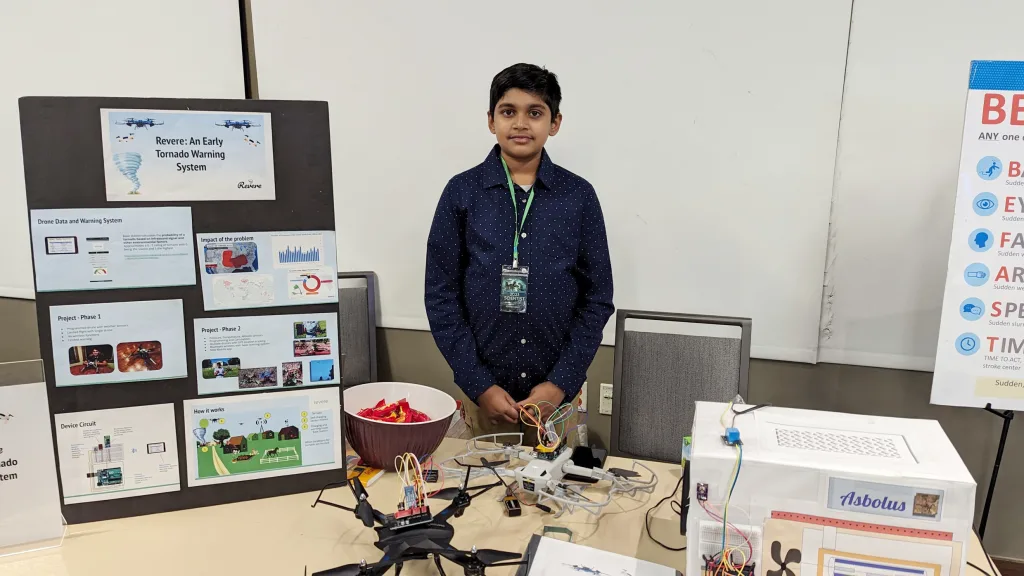

When Anirudh Rao was 4 years old and living in Nashville, his friend’s house was destroyed by a tornado. A year later—yes, as a kindergartner—Rao started sketching a potential solution for better tornado warnings.

Now 12 years old and living in Colorado, Rao is pursuing a more advanced version of his concept: a network of drones that could theoretically sense infrasound, a wave phenomenon emitted before and during tornadoes with frequencies below the threshold of human hearing.

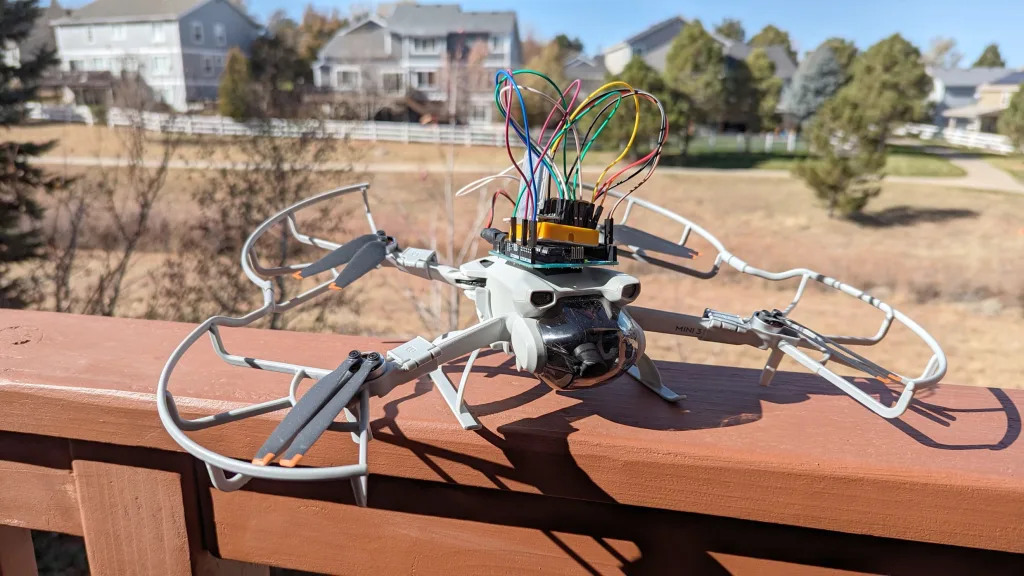

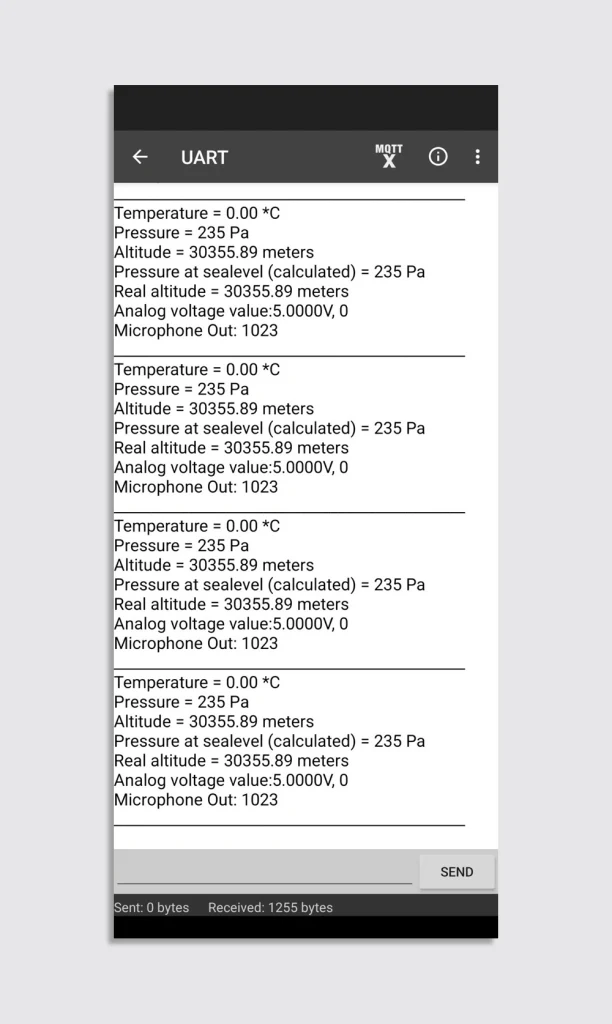

“On the outskirts of the city, there’ll be a base station and a network of autonomous drones that fly in all directions,” says Rao. He envisions sensors detecting infrasound along with temperature, pressure, and altitude, and sending data back to the base station; if a tornado is detected, that information could go to local authorities to trigger an official tornado warning and push notifications on phones.

Currently tornadoes are detected as they have been for decades: through radar and by storm chasers visually spotting them on the ground. But radar doesn’t work perfectly. As storms have started to move east out of the traditional “Tornado Alley” in the center of the country (a trend that may be happening because of climate change), they’re also moving into hillier topography, where radar is even less reliable. As tornadoes are shifting eastward, they’re also reaching more populated areas, increasing the risk.

Rao’s instinct to use infrasound is in line with the latest science. The idea isn’t new, though until tornado patterns changed, radar had been considered good enough. “As tornadoes move into hillier areas and it limits the effectiveness of radar [science is] refocusing on the potential use of infrasound,” says Brian Elbing, a mechanical and aerospace engineering professor at Oklahoma State University.

Though it still isn’t fully understood how tornadoes produce infrasound, “you can pick up the signal before the tornado touches the ground, and it lasts the life of the tornado,” Elbing says. “And it carries information about the strength of the tornado.”

Rao’s theory is that rather than building large stationary sensors for infrasound, drones could cover more ground. “My bigger idea was to use the fact that infrasound produced by tornadoes travels hundreds of miles,” he says. “Instead of waiting for it to come closer and then detect it using Doppler [radar], drones can fly outwards in all directions to offer an opportunity to reach out to a potential tornado, thus reducing the detection time and increasing the warning time.” (He calls his concept Revere, named after Paul Revere’s warning during the Revolutionary War.)

There are challenges, including the fact that the noise from wind interferes with the sensors that detect infrasound. Rao argues that it’s possible to physically shield the sensor and then filter the signal. Altitude is another challenge, since the pressure would change as the drone flies, but Rao thinks that’s also surmountable.

Ebling believes that a stationary network of sensors measuring infrasound is more likely. It would be cheaper to use than radar, and more accurate, so people could feel more confident that a warning wasn’t a false alarm. As the science advances, he says it could be feasible to build commercial networks of sensors as soon as a decade from now.

Rao, meanwhile, is continuing to pursue his idea, while also working on an array of other inventions, from a sensor that could measure moisture in wounds to help avoid infection to a biomimetic surface for roads that could help ice melt faster. “I’m really interested in science, and I believe science can solve a lot of problems,” says Rao, who is a National STEM champion and was recently honored by a platform called Young Planet Leaders.

![How to Find Low-Competition Keywords with Semrush [Super Easy]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/73/62/7362f16fb9e460b6d58ccc09b4a048b6/how-to-find-low-competition-keywords-sm.png)