How video games became peak IP

The Minecraft movie is crass, dumb, and barely coherent. It also just made almost $163 million at the domestic box office over its opening weekend. Video game adaptations have been on a hot streak in recent years. In 2023, The Super Mario Bros. Movie crossed the billion-dollar mark, nearly unseating Barbie as the year’s top-grossing film. Amazon’s Fallout shattered records with 2.5 billion viewing minutes in its debut week. And now, A Minecraft Movie stands as the highest-grossing film since Deadpool & Wolverine. Hollywood’s obsession with intellectual property—from comic book heroes to kids’ toys—is nothing new. But for decades, video games were the outliers: critically panned, commercial duds. That’s no longer the case. Today, they’re becoming studios’ most reliable path to profit. The long history of video game movie flops While a few video game films trickled out in the late 1990s, the first major wave of studio-backed adaptations hit in the early 2000s. Many of these were helmed by German director Uwe Boll, who became notorious for a steady stream of critical and commercial failures. BloodRayne barely scraped together $3 million at the box office; Alone in the Dark grossed just over $12 million on a $20 million budget. In the Name of the King, starring Jason Statham, bizarrely carried a $60 million price tag but pulled in only $12 million. (Boll himself admitted that Alone in the Dark—with Christian Slater and Tara Reid—was “not good.”) By the early 2010s, studios leaned into flashy visual effects to boost video game adaptations. These films made modest profits but often alienated audiences. Max Payne, starring Mark Wahlberg, scored just 16% on Rotten Tomatoes and earned Wahlberg a Golden Raspberry Award (better known as a Razzie). Disney’s Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, fronted by Jake Gyllenhaal, was pitched as the next Pirates of the Caribbean-style franchise. That dream died quickly after the CGI-heavy film was trounced at the box office by Sex and the City 2 and Shrek Forever After. Around the same time, game developers began chasing global markets, especially in Asia—and most notably, China. That expansion opened new international audiences for video game films. The strategy peaked in 2016, when Universal released Warcraft. Though critics panned it and American audiences mostly shrugged, the film soared in China, earning more than $100 million there despite failing to reach $50 million in the U.S. Even as box office numbers climbed, video game movies still carried the stigma of cheap storytelling and poor production. The late 2010s and early 2020s saw a mix of live-action flops like Mortal Kombat and animated crowd-pleasers like Sonic the Hedgehog and Detective Pikachu. They all turned a profit—but they’re often better remembered for their internet backlash than cinematic impact. When gaming adaptations started soaring Then, almost unexpectedly, these cash-grab adaptations started getting . . . better. Or at least good enough to justify their existence beyond box office potential. The Super Mario Bros. Movie didn’t just rake in $1.3 billion—it also delivered a viral hit with Jack Black’s “Peaches.” Critics may have panned Five Nights at Freddy’s, but audiences embraced it, giving it an 86% audience score on Rotten Tomatoes and contributing to nearly $300 million in global revenue. Video games have also made major inroads into prestige television. HBO gave The Last of Us the coveted Sunday night slot, and the show went on to earn five Primetime Emmy nominations, including Outstanding Drama Series. Amazon’s Fallout became the platform’s biggest premiere ever—even surpassing YouTube juggernaut MrBeast’s game show in viewership—and it, too, snagged a nomination for Outstanding Drama Series. Now comes A Minecraft Movie. Is it good? Not really. But it’s a box office magnet—just ask the legions of middle schoolers screaming “Chicken jockey!” and causing public disruptions in theaters. It’s the clearest sign yet of the genre’s evolution. Video game adaptations are no longer synonymous with bad CGI and low returns. They’ve officially entered the IP big leagues.

The Minecraft movie is crass, dumb, and barely coherent. It also just made almost $163 million at the domestic box office over its opening weekend.

Video game adaptations have been on a hot streak in recent years. In 2023, The Super Mario Bros. Movie crossed the billion-dollar mark, nearly unseating Barbie as the year’s top-grossing film. Amazon’s Fallout shattered records with 2.5 billion viewing minutes in its debut week. And now, A Minecraft Movie stands as the highest-grossing film since Deadpool & Wolverine.

Hollywood’s obsession with intellectual property—from comic book heroes to kids’ toys—is nothing new. But for decades, video games were the outliers: critically panned, commercial duds. That’s no longer the case. Today, they’re becoming studios’ most reliable path to profit.

The long history of video game movie flops

While a few video game films trickled out in the late 1990s, the first major wave of studio-backed adaptations hit in the early 2000s. Many of these were helmed by German director Uwe Boll, who became notorious for a steady stream of critical and commercial failures. BloodRayne barely scraped together $3 million at the box office; Alone in the Dark grossed just over $12 million on a $20 million budget. In the Name of the King, starring Jason Statham, bizarrely carried a $60 million price tag but pulled in only $12 million. (Boll himself admitted that Alone in the Dark—with Christian Slater and Tara Reid—was “not good.”)

By the early 2010s, studios leaned into flashy visual effects to boost video game adaptations. These films made modest profits but often alienated audiences. Max Payne, starring Mark Wahlberg, scored just 16% on Rotten Tomatoes and earned Wahlberg a Golden Raspberry Award (better known as a Razzie). Disney’s Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, fronted by Jake Gyllenhaal, was pitched as the next Pirates of the Caribbean-style franchise. That dream died quickly after the CGI-heavy film was trounced at the box office by Sex and the City 2 and Shrek Forever After.

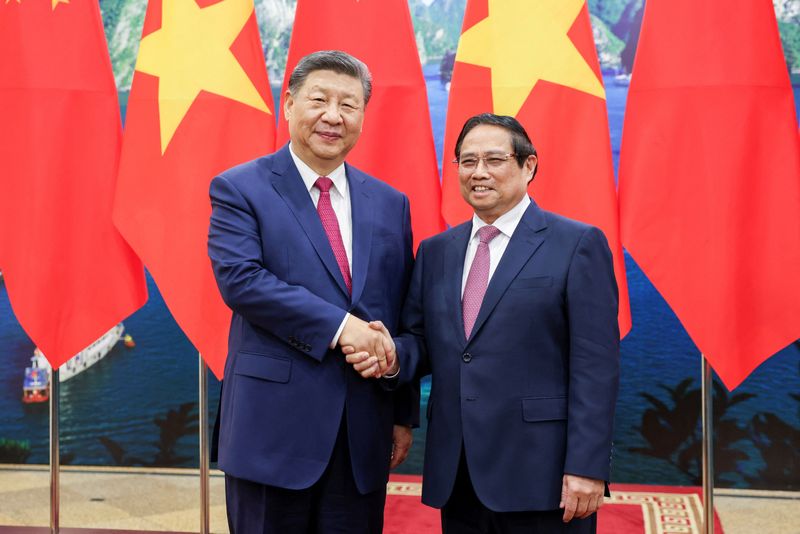

Around the same time, game developers began chasing global markets, especially in Asia—and most notably, China. That expansion opened new international audiences for video game films. The strategy peaked in 2016, when Universal released Warcraft. Though critics panned it and American audiences mostly shrugged, the film soared in China, earning more than $100 million there despite failing to reach $50 million in the U.S.

Even as box office numbers climbed, video game movies still carried the stigma of cheap storytelling and poor production. The late 2010s and early 2020s saw a mix of live-action flops like Mortal Kombat and animated crowd-pleasers like Sonic the Hedgehog and Detective Pikachu. They all turned a profit—but they’re often better remembered for their internet backlash than cinematic impact.

When gaming adaptations started soaring

Then, almost unexpectedly, these cash-grab adaptations started getting . . . better. Or at least good enough to justify their existence beyond box office potential. The Super Mario Bros. Movie didn’t just rake in $1.3 billion—it also delivered a viral hit with Jack Black’s “Peaches.” Critics may have panned Five Nights at Freddy’s, but audiences embraced it, giving it an 86% audience score on Rotten Tomatoes and contributing to nearly $300 million in global revenue.

Video games have also made major inroads into prestige television. HBO gave The Last of Us the coveted Sunday night slot, and the show went on to earn five Primetime Emmy nominations, including Outstanding Drama Series. Amazon’s Fallout became the platform’s biggest premiere ever—even surpassing YouTube juggernaut MrBeast’s game show in viewership—and it, too, snagged a nomination for Outstanding Drama Series.

Now comes A Minecraft Movie. Is it good? Not really. But it’s a box office magnet—just ask the legions of middle schoolers screaming “Chicken jockey!” and causing public disruptions in theaters. It’s the clearest sign yet of the genre’s evolution. Video game adaptations are no longer synonymous with bad CGI and low returns. They’ve officially entered the IP big leagues.

![How to Find Low-Competition Keywords with Semrush [Super Easy]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/73/62/7362f16fb9e460b6d58ccc09b4a048b6/how-to-find-low-competition-keywords-sm.png)