Bot farms invade social media to hijack popular sentiment

Welcome to the world of social media mind control. By amplifying free speech with fake speech, you can numb the brain into believing just about anything. Surrender your blissful ignorance and swallow the red pill. You’re about to discover how your thinking is being engineered by modern masters of deception. The means by which information gets drilled into our psyches has become automated. Lies are yesterday’s problem. Today’s problem is the use of bot farms to trick social media algorithms into making people believe those lies are true. A lie repeated often enough becomes truth. “We know that China, Iran, Russia, Turkey, and North Korea are using bot networks to amplify narratives all over the world,” says Ran Farhi, CEO of Xpoz, a threat detection platform that uncovers coordinated attempts to spread lies and manipulate public opinion in politics and beyond. Bot farm amplification is being used to make ideas on social media seem more popular than they really are. A bot farm consists of hundreds and thousands of smartphones controlled by one computer. In data-center-like facilities, racks of phones use fake social media accounts and mobile apps to share and engage. The bot farm broadcasts coordinated likes, comments, and shares to make it seem as if a lot of people are excited or upset about something like a volatile stock, a global travesty, or celebrity gossip—even though they’re not. Meta calls it “coordinated inauthentic behavior.” It fools the social network’s algorithm into showing the post to more people because the system thinks it’s trending. Since the fake accounts pass the Turing test, they escape detection. Unlike conventional bots that rely on software and API access, bot farm amplification uses real mobile phones. Racks and racks of smartphones connected to USB hubs are set up with SIM cards, mobile proxies, IP geolocation spoofing, and device fingerprinting. That makes them far more difficult to detect than the bots of yore. “It’s very difficult to distinguish between authentic activity and inauthentic activity,” says Adam Sohn, CEO of Narravance, a social media threat intelligence firm with major social networks as clients. “It’s hard for us, and we’re one of the best at it in the world.” Disinformation, Depression-era-style Distorting public perception is hardly a new phenomenon. But in the old days, it was a highly manual process. Just months before the 1929 stock market crash, Joseph P. Kennedy, JFK’s father, got richer by manipulating the capital markets. He was part of a secret trading pool of wealthy investors who used coordinated buying and media hype to artificially pump the price of Radio Corp. of America shares to astronomical levels. After that, Kennedy and his rich friends dumped their RCA shares at a huge profit, the stock collapsed, and everyone else lost their asses. After the market crashed, President Franklin D. Roosevelt made Kennedy the first chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, putting the fox in charge of the henhouse. Today, stock market manipulators use bot farms to amplify fake posts about “hot” stocks on Reddit, Discord, and X. Bot networks target messages laced with ticker symbols and codified slang phrases like “c’mon fam,” “buy the dip,” “load up now” and “keep pushing.” The self-proclaimed finfluencers behind the schemes are making millions in profit by coordinating armies of avatars, sock puppets, and bots to hype thinly traded stocks so they can scalp a vig after the price increases. “We find so many instances where there’s no news story,” says Adam Wasserman, CFO of Narravance. “There’s no technical indicator. There are just bots posting things like ‘this stock’s going to the moon’ and ‘greatest stock, pulling out of my 401k.’ But they aren’t real people. It’s all fake.” In a world where all information is now suspect and decisions are based on sentiment, bot farm amplification has democratized market manipulation. But stock trading is only one application. Anyone can use bot farms to influence how we invest, make purchasing decisions, or vote. These are the same strategies behind propaganda efforts pioneered by Russia and the Islamic State to broadcast beheadings and sway elections. But they’ve been honed to sell stocks, incite riots, and, allegedly, even tarnish celebrity reputations. It’s the same song, just different lyrics. “People under the age of 30 don’t go to Google anymore,” says Jacki Alexander, CEO at pro-Israel media watchdog HonestReporting. “They go to TikTok and Instagram and search for the question they want to answer. It requires zero critical thinking skills but somehow feels more authentic. You feel like you’re making your own decisions by deciding which videos to watch, but you’re actually being fed propaganda that’s been created to skew your point of view.” It’s not an easy problem to solve. And social media companies appear to be buckling to inauthenticity. After Elon Musk took over Twitter (now X), the company fired much

Welcome to the world of social media mind control. By amplifying free speech with fake speech, you can numb the brain into believing just about anything. Surrender your blissful ignorance and swallow the red pill. You’re about to discover how your thinking is being engineered by modern masters of deception.

The means by which information gets drilled into our psyches has become automated. Lies are yesterday’s problem. Today’s problem is the use of bot farms to trick social media algorithms into making people believe those lies are true. A lie repeated often enough becomes truth.

“We know that China, Iran, Russia, Turkey, and North Korea are using bot networks to amplify narratives all over the world,” says Ran Farhi, CEO of Xpoz, a threat detection platform that uncovers coordinated attempts to spread lies and manipulate public opinion in politics and beyond.

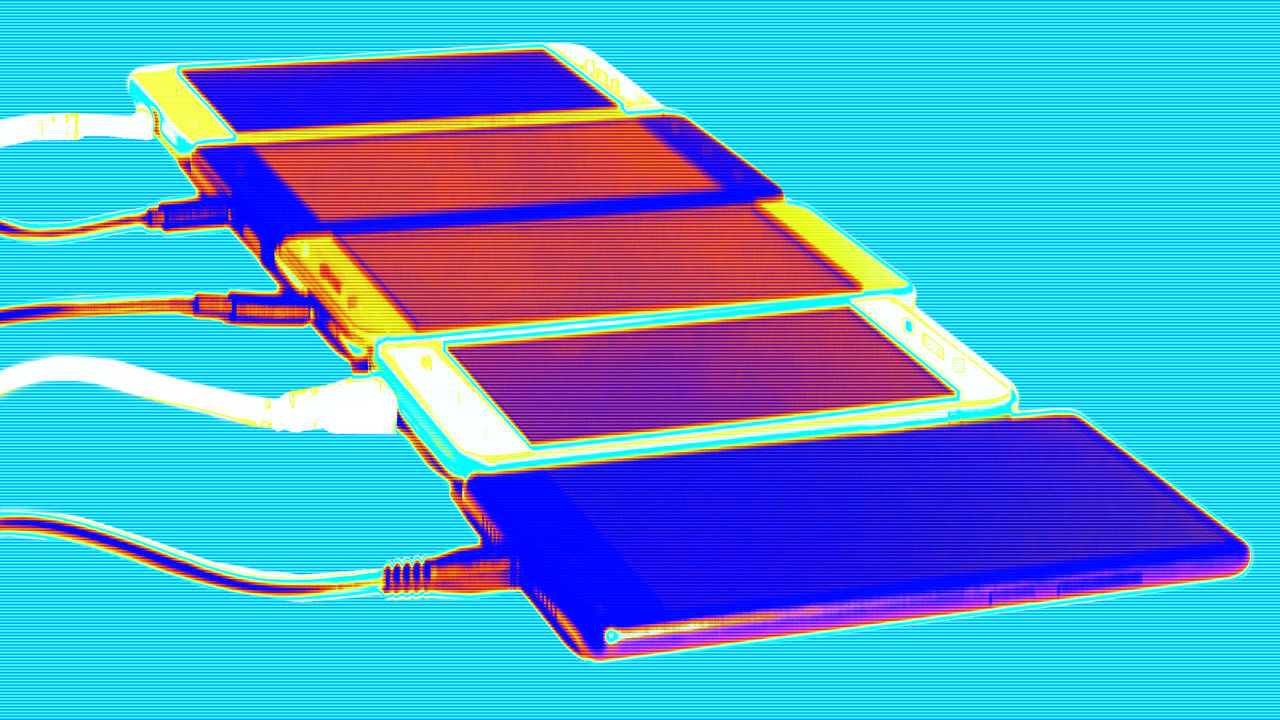

Bot farm amplification is being used to make ideas on social media seem more popular than they really are. A bot farm consists of hundreds and thousands of smartphones controlled by one computer. In data-center-like facilities, racks of phones use fake social media accounts and mobile apps to share and engage. The bot farm broadcasts coordinated likes, comments, and shares to make it seem as if a lot of people are excited or upset about something like a volatile stock, a global travesty, or celebrity gossip—even though they’re not.

Meta calls it “coordinated inauthentic behavior.” It fools the social network’s algorithm into showing the post to more people because the system thinks it’s trending. Since the fake accounts pass the Turing test, they escape detection.

Unlike conventional bots that rely on software and API access, bot farm amplification uses real mobile phones. Racks and racks of smartphones connected to USB hubs are set up with SIM cards, mobile proxies, IP geolocation spoofing, and device fingerprinting. That makes them far more difficult to detect than the bots of yore.

“It’s very difficult to distinguish between authentic activity and inauthentic activity,” says Adam Sohn, CEO of Narravance, a social media threat intelligence firm with major social networks as clients. “It’s hard for us, and we’re one of the best at it in the world.”

Disinformation, Depression-era-style

Distorting public perception is hardly a new phenomenon. But in the old days, it was a highly manual process. Just months before the 1929 stock market crash, Joseph P. Kennedy, JFK’s father, got richer by manipulating the capital markets. He was part of a secret trading pool of wealthy investors who used coordinated buying and media hype to artificially pump the price of Radio Corp. of America shares to astronomical levels.

After that, Kennedy and his rich friends dumped their RCA shares at a huge profit, the stock collapsed, and everyone else lost their asses. After the market crashed, President Franklin D. Roosevelt made Kennedy the first chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, putting the fox in charge of the henhouse.

Today, stock market manipulators use bot farms to amplify fake posts about “hot” stocks on Reddit, Discord, and X. Bot networks target messages laced with ticker symbols and codified slang phrases like “c’mon fam,” “buy the dip,” “load up now” and “keep pushing.” The self-proclaimed finfluencers behind the schemes are making millions in profit by coordinating armies of avatars, sock puppets, and bots to hype thinly traded stocks so they can scalp a vig after the price increases.

“We find so many instances where there’s no news story,” says Adam Wasserman, CFO of Narravance. “There’s no technical indicator. There are just bots posting things like ‘this stock’s going to the moon’ and ‘greatest stock, pulling out of my 401k.’ But they aren’t real people. It’s all fake.”

In a world where all information is now suspect and decisions are based on sentiment, bot farm amplification has democratized market manipulation. But stock trading is only one application. Anyone can use bot farms to influence how we invest, make purchasing decisions, or vote.

These are the same strategies behind propaganda efforts pioneered by Russia and the Islamic State to broadcast beheadings and sway elections. But they’ve been honed to sell stocks, incite riots, and, allegedly, even tarnish celebrity reputations. It’s the same song, just different lyrics.

“People under the age of 30 don’t go to Google anymore,” says Jacki Alexander, CEO at pro-Israel media watchdog HonestReporting. “They go to TikTok and Instagram and search for the question they want to answer. It requires zero critical thinking skills but somehow feels more authentic. You feel like you’re making your own decisions by deciding which videos to watch, but you’re actually being fed propaganda that’s been created to skew your point of view.”

It’s not an easy problem to solve. And social media companies appear to be buckling to inauthenticity. After Elon Musk took over Twitter (now X), the company fired much of its anti-misinformation team and reduced the transparency of platform manipulation. Meta is phasing out third-party fact-checking. And YouTube rolled back features meant to combat misinformation.

“On TikTok, you used to be able to see how many times a specific hashtag was shared or commented on,” says Alexander. “But they took those numbers down after news articles came out showing the exact same pro-Chinese propaganda videos got pushed up way more on TikTok than Instagram.” Algorithmically boosting specific content is a practice known as “heating.”

If there’s no trustworthy information, what we think will likely become less important than how we feel. That’s why we’re regressing from the Age of Science—when critical thinking and evidence-based reasoning were central—back to something resembling the Edwardian era, which was driven more by emotional reasoning and deference to authority.

When Twitter introduced microblogging, it was liberating. We all thought it was a knowledge amplifier. We watched it fuel a pro-democracy movement that swept across the Middle East and North Africa called the Arab Spring and stoke national outrage over racial injustice in Ferguson, Missouri, planting the seeds for Black Lives Matter.

While Twitter founders Evan Williams and Jack Dorsey thought they were building a platform for political and social activism, their trust and safety team was getting overwhelmed with abuse. “It’s like they never really read Lord of the Flies. People who don’t study literature or history, they don’t have any idea of what could happen,” said tech journalist Kara Swisher in Breaking the Bird, a CNN documentary about Twitter.

Your outrage has been cultivated

Whatever gets the most likes, comments, and shares gets amplified. Emotionally charged posts that lure the most engagement get pushed up to the top of the news feed. Enrage to engage is a strategy. “Social media manipulation has become very sophisticated,” says Wendy Sachs, director-producer of October 8, a documentary about the campus protests that erupted the day after the October 7th Hamas attack on Israel. “It’s paid for and funded by foreign governments looking to divide the American people.”

Malicious actors engineer virality by establishing bots that leach inside communities for months, sometimes years, before they get activated. The bots are given profile pics and bios. Other tricks include staggering bot activity to occur in local time zones, using U.S. device fingerprinting techniques like setting the smartphone’s internal clock to the time zone to where an imaginary “user” supposedly lives, and setting the phone’s language to English.

Using AI-driven personas with interests like cryptocurrency or dogs, bots are set to follow real Americans and cross-engage with other bots to build up perceived credibility. It’s a concept known as social graph engineering, which involves infiltrating broad interest communities that align with certain biases, such as left- or right-leaning politics.

For example, the K-pop network BTS Army has been mobilized by liberals, while Formula 1 networks might lend themselves to similar manipulation from conservatives. The bots leach inside these communities and earn trust through participation before agitating from within.

“Bot accounts lay dormant, and at a certain point, they wake up and start to post synchronously, which is what we’ve observed they actually do,” says Valentin Châtelet, research associate at the Digital Forensic Research Lab of the Atlantic Council. “They like the same post to increase its engagement artificially.”

To set up and manage thousands of fake social media accounts, some analysts believe that bot farms are deployed with the help of cyber criminal syndicates and state sponsorship, giving them access to means that are not ordinary.

Bot handlers build workflows with enough randomness to make them seem organic. They set them to randomly reshare or comment on trending posts with certain keywords or hashtags, which the algorithm then uses to personalize the bot’s home feed with similar posts. The bot can then comment on home feed posts, stay on topic, and dwell deeper inside the community.

This workflow is repetitive, but the constant updates on the social media platform make the bot activity look organic. Since social media platforms update frequently, programmed bots appear spontaneous and natural.

Software bots posted spam, also known as copypasta, which is a block of text that gets repeatedly copied and pasted. But the bot farmers use AI to author unique, personalized posts and comments. Integrating platforms like ChatGPT, Gemini, and Claude into a visual flow-building platform like Make.com, bots can be programmed with advanced logic and conditional paths and use deep integrations leveraging large language models to sound like a 35-year-old libertarian schoolteacher from the Northwest, or a MAGA auto mechanic from the Dakotas.

The speed at which AI image creation is developing dramatically outpaces the speed at which social networking algorithms are advancing. “Social media algorithms are not evolving quick enough to outperform bots and AI,” says Pratik Ratadiya, a researcher with two advanced degrees in computer science who’s worked at JPL and Apple, and who currently leads machine learning at Narravance. “So you have a bunch of accounts, influencers, and state actors who easily know how to game the system. In the game of cat and mouse, the mice are winning.”

Commercial bot farms charge around a penny per action to like posts, follow accounts, leave comments, watch videos, and visit websites. Sometimes positioned as “growth marketing services” or “social media marketing panels,” commercial bot farms ply their trades on gig marketplaces like Fiverr and Upwork, as well as direct to consumer through their own websites.

Bot farms thrive in countries where phone numbers, electricity, and labor are cheap, and government oversight is minimal. A new book about Vietnamese bot farms by photographer Jack Latham called Beggar’s Honey offers a rare look into Hanoi’s attention sweatshops.

Sentiment breeding

Before free speech colluded with fake speech online, traders used fundamental analysis and technical analysis to decide what and when to buy. Today, fund managers and quants also use sentiment analysis to gauge the market’s mood and anticipate volatility. Sentiment scores are even fed into trading algorithms to automatically adjust exposure and trigger trades.

Courts recently dismissed a securities fraud claim against a group of online influencers called the Goblin Gang, who made millions buying up shares of thinly traded, low-float stocks, which they promoted aggressively on Twitter, Discord, and their podcast. Once followers bought into the stock—which, in turn, pumped up the share price—the defendants dumped their shares at inflated prices without disclosing it to their flock.

The court dismissed the indictment because the government failed to prove a scheme to defraud. Expressing enthusiasm, even if it is exaggerated, didn’t meet the legal threshold for securities fraud. On March 21, 2025, Bloomberg columnist Matt Levine wrote an opinion piece titled “Pump and Dumps Are Legal Now.”

Chatterflow, a service from Narravance, alerts subscribers to roughly 10 stocks a day, with 2 to 4 seeing sharp, short-term moves from social media chatter. The sentiment monitoring platform cross-references unusual social media chatter against EDGAR filings, analyst reports, newswires, and other material disclosures to identify unusual spikes in chatter originating on social media. The service also weights participants driving social media conversations for engagement and authenticity.

“When we dig into the online chatter behind the alerts, at least half of them are bots,” says Wasserman. “We keep records. But most of the time, after the stock price jumps, the social media accounts that instigated the frenzy get instantly deleted.” On X, residue from the deleted posts often lingers, preserved through retweets by genuine users.

Due to potential legal risks from investors who profited off trades and companies whose stock prices surged, Narravance agreed to share evidence of numerous publicly traded stocks that saw big daily increases on the condition that their ticker symbols not be published.

To distinguish correlation from causation, in the case of Silicon Valley Bank’s 2023 collapse, social media chatter also played a role, but that chatter was organic. Bloomberg reported that Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund was advising its portfolio companies to withdraw funds due to concerns about the bank’s solvency. Bloomberg reported that those warnings, which were made through direct communications, triggered private discussions among venture capitalists and startup founders on WhatsApp, email chains, and text grists, which spilled over onto Twitter and LinkedIn, amplifying panic and sparking the digital bank run that led to its collapse.

Similarly, the GameStop rally of early 2021 is a compelling example of how retail investors, galvanized by social media channels like Reddit’s r/WallStreetBets, pumped up a stock price targeted by institutional short sellers. Their collective action led to a dramatic short squeeze, causing GameStop’s stock price to surge by approximately 1,500% over two weeks.

Spawning deceptive mass influence

On October 7, 2023, as Hamas launched its deadly terror attack into Israel, a coordinated disinformation campaign—powered by Russian and Iranian bot networks—flooded social media with false claims suggesting the attack was an inside job. Social media posts in Hebrew on X with messages like “There are traitors in the army” and “Don’t trust your commanders” were overwhelmed with retweets, comments, and likes from bot accounts.

Russian and Iranian bot farms promote pro-Palestinian misinformation to inflame divisions in the West. Their objective is to pit liberals against conservatives. They amplify Hamas’s framing of the conflict as a civil rights issue, rather than the terrorist organization’s real agenda—which is the destruction of the state of Israel and the expansion of Shariah law and Islamic fundamentalism. The social media posts selected for coordinated amplification by Russian and Iranian actors tend to frame Palestinians exclusively as victims, promoting simplistic victim-victimizer or colonizer-Indigenous narratives—false binaries amplified not to inform but to inflame and divide democratic societies from within.

Bot farm amplification can’t be undone. The same deceptive forces used bot farms to boost posts about a New York Times report that falsely blamed Israel for a bomb that hit a hospital in Gaza that reportedly killed 500 Palestinians. It was later revealed that the blast was actually caused by a rocket misfire from jihadists. The New York Times updated its headline twice. But you can’t put deceptive mass influence back in the bottle.

In the case of the war in Gaza, bot farms may not be solely to blame. “The Twitter algorithm is pretty nefarious,” says Ahmed Fouad Alkhatib, Gaza writer and analyst and senior fellow at the Atlantic Council. “I really think it optimizes for hate and division to drive engagement and revenue.” Perhaps Twitter is just more bot-farm-friendly?

Xpoz collected evidence of a global bot farm amplification campaign by Russia-, Iran-, and China-backed bot farms to frame what Hamas admits in Arabic is a religious crusade to expand the Islamic state as a civil rights battle for freedom and justice against Israeli oppressors in English. In another example, Xpoz found that the same bot network amplifying antisemitic hate speech in Arabic was also being used to amplify tweets critical of Ukraine in German.

In the case of the pro-Palestinian campus protests, they erupted before the Israeli death toll from the Hamas attack had even been established. How could it happen so quickly? Radical Islamic terrorists were still on the loose inside Israel. The film October 8 explores how college campuses turned against Israel less than 24 hours after the biggest massacre of Jews since the Holocaust.

“We think most of what we see online is real. But most of what we see is deceptive,” said Ori Shaashua, who is chairman of Xpoz and an AI entrepreneur behind a host of other tech ventures. Shaashua’s team analyzed the ratio between bots, avatars, and humans. “It doesn’t make sense when 418 social media accounts generate 3 million views in two hours,” says Shaashua.

Before the release of October 8, Sachs’s IMDb page was flooded with hundreds of 1-star ratings. “They’re obviously just haters because they haven’t even seen the film,” the producer-director said. In response, she encouraged audiences at screenings to leave reviews to counter the abuse. She got 6,300 10-star ratings, pushing her film’s unweighted average to 9.1 by the end of last month. On April 1, bots had added more than 1,000 new 1-star reviews. Three weeks later, it had 4,700 1-stars and 10,000 10-stars, dragging its IMDb rating down to just 4.3 stars.

In a bot-driven world, engagement metrics are no longer a reflection of authenticity. As the automated jiggering of reviews grows more pervasive, we’ve entered an era where star ratings have little value—especially on topics where passions run high, but increasingly even where they don’t.

Cloning celebrity gossip

Bot farms manufacture familiarity until it feels like truth—not just in politics or capital markets, but in lifestyle and entertainment, too. On December 20, 2024, actress Blake Lively filed a lawsuit against actor-director Justin Baldoni and others, alleging harassment, intimidation, and retaliation after the A-lister reported concerns about inappropriate behavior on the set of It Ends With Us.

Lively’s claim alleges that Baldoni and Wayfarer Studios (which Baldoni cofounded) retained a crisis PR firm, the Agency Group, to execute a strategy involving astroturfing and digital manipulation—orchestrated, deceptive online engagement made to look grassroots. The claim says it included using bots, coordinated Reddit and TikTok threads, and fake fan engagement to manipulate public sentiment against Lively.

“I can’t connect it to Baldoni, but I can say there is evidence of synthetic activity that is not human,” said Ori Lehavi, an independent threat consultant who analyzed the Lively-Baldoni incident on Xpoz. The analysis showed that bot farm amplification activity had been coordinated against Lively. The preemptive surge in coordinated, inauthentic bot-like activity that Lehavi found came on December 20, 2024, a day before The New York Times broke the story about Lively’s allegations.

On that day, bot-like activity spiked to 19,411 engagements, amplifying the reach of posts about Lively to a potential audience of 202,540,776 viewers. Bot farm amplification appears to have sparked organic activity as well. There were 2,913 human-like posts on the day of the bot surge, rising to 3,772 the following day and 4,734 the day after that—even though the bot-like activity subsided.

One week later, Baldoni filed a libel lawsuit against The New York Times seeking $250 million for running a story based on “cherry-picked evidence” with “false allegations of a smear campaign.”

As is common in bot farm amplification, the most active X accounts used to bash Lively have since been removed. In this case, two of the most outspoken profiles were a suspended account with the username @schuld_eth, and a deleted account called @leapordprint_princess.

The legal battles around these allegations continue to unfold.

It’s not just the bots that are gaming the algorithms through mass amplification. It’s also the algorithms that are gaming us. We’re being subtly manipulated by social media. We know it. But we keep on scrolling.

![How to Find Low-Competition Keywords with Semrush [Super Easy]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/73/62/7362f16fb9e460b6d58ccc09b4a048b6/how-to-find-low-competition-keywords-sm.png)