The U.S. needs critical minerals. Can we get them without sacrificing our oceans?

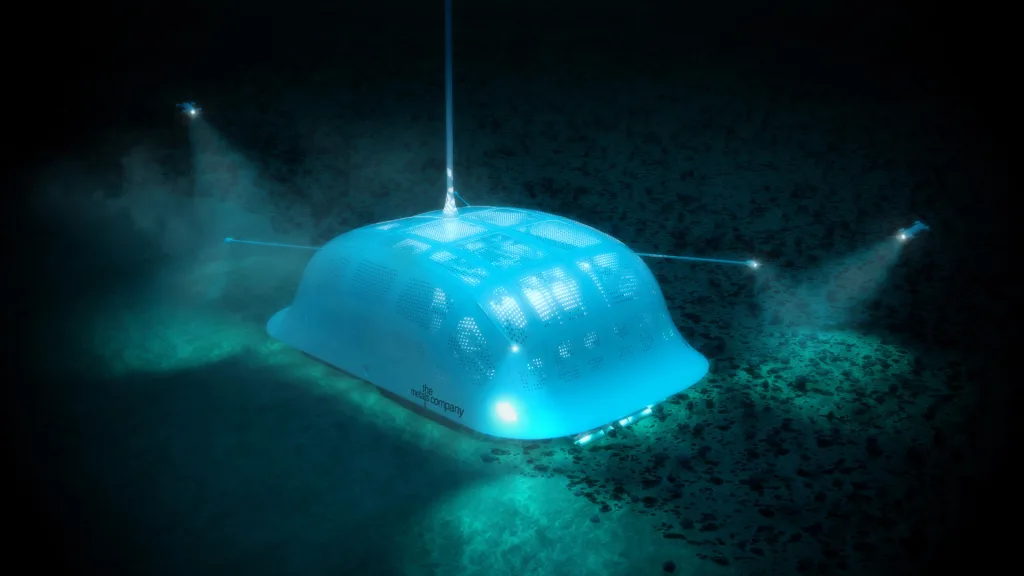

Oceans cover about 70% of the Earth’s surface, yet the ocean floor remains largely untouched by humans. But perhaps not for long. A Canadian-based firm called the Metals Co. (TMC) recently announced plans to ask the Trump administration to allow it to mine the deep seabed for valuable critical metals in the Pacific Ocean. President Donald Trump is reportedly considering an executive order that would speed up permitting for deep-sea mining, which has prompted outrage from other countries. While some small and exploratory deep-sea mining operations already exist, the practice has yet to happen on a large commercial scale, partly due to fears that it could cause catastrophic damage to the pristine seafloor environment and the wealth of life harbored there. But the worsening climate crisis and the urgent need to transition away from fossil fuels has put deep-sea mining in the spotlight. Clean energy technologies like solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries contain critical minerals like nickel, lithium, cobalt, copper, and manganese, and concerns are growing over whether we’ll have enough of these materials to meet near-term net-zero goals. Some companies have pitched deep-sea mining as a solution. But would the risks be worth the potential rewards? Into the deep TMC’s mining process would involve collecting potato-size balls of rock, known as polymetallic nodules, that rest gently on top of the seafloor sediment and contain various critical minerals. These nodules have formed over millions of years, and they carpet vast swathes of the seabed. A large rover-like machine would be lowered from a ship down to the seafloor where it would gather the nodules and send them back up to the ship. (To give you a sense of depth, the area in the Pacific where TMC wants to mine, called the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), is a deep-sea abyssal plain some 2.5 miles down and is estimated to hold 21 billion tons of nodules.) The water and sediment that comes up with the nodules would then be pumped back into the ocean. A 2021 concept rendering of a Metals Co. mining device [Image: Bjarke Ingels Group/The Metals Co.] The company says it would pay “careful attention not to harm the integrity of the deep-ocean ecosystem” during this process and plans to use a real-time monitoring program that will enable it to “adapt, pause, and change . . . operations to stay within expected ecological thresholds.” But the nodules themselves are an essential part of that ecosystem, and removing them would have consequences. Nodules are among the only hard surfaces in a vast plain of sludgy sediment, and serve as a habitat for many slow-growing and unique creatures, including sea sponges, corals, and octopuses. And the CCZ likely contains many thousands of species that have yet to be identified. Research suggests that removing the nodules “would lead to a loss of food-web integrity and a significant depreciation of faunal biodiversity.” Disturbing the ocean food web could have cascading effects, putting many fish populations at risk and threatening the livelihoods and food security of millions of people. (The Trump administration did not respond to request for comment by the time of publication.) There are other concerns. The mere presence of the rover itself in an environment that has remained untouched for millennia would likely disturb its living organisms, most of which exist in the top 2 inches of sediment, explains Oliver Ashford, a marine biologist with the World Resources Institute’s Ocean Program. “The organisms there aren’t really adapted to rapidly changing currents and being thrown around and disrupted,” he says. “They’re quite delicate organisms normally. So the physical interaction with that machine might cause death.” A recent study published in the journal Nature found that life at a small deep-sea mining test site in the CCZ is still recovering four decades after the tests were conducted. The creatures that aren’t physically disturbed by the rover could be harmed by changes in temperature, light, and sound. The activity could stir up large plumes of sediment that get picked up by ocean currents and spread across hundreds of miles, smothering and starving sponges and coral and disrupting fishing activities. There’s even some concern that mining could interfere with the ocean’s natural ability to sequester carbon and produce oxygen, further harming the Earth’s climate. TMC doesn’t deny that deep-sea mining comes with environmental risks, but says “the clean energy transition will require trade-offs.” Who’s in charge around here? The U.N.’s International Seabed Authority is responsible for setting environmental and financial regulations for the nascent deep-sea mining industry, but has yet to do so even after years of deliberations. “They’re developing regulations from scratch for an industry that could potentially have a large environmental impact,” Ashford says of the ISA. “I feel like it’s a

Oceans cover about 70% of the Earth’s surface, yet the ocean floor remains largely untouched by humans. But perhaps not for long.

A Canadian-based firm called the Metals Co. (TMC) recently announced plans to ask the Trump administration to allow it to mine the deep seabed for valuable critical metals in the Pacific Ocean. President Donald Trump is reportedly considering an executive order that would speed up permitting for deep-sea mining, which has prompted outrage from other countries. While some small and exploratory deep-sea mining operations already exist, the practice has yet to happen on a large commercial scale, partly due to fears that it could cause catastrophic damage to the pristine seafloor environment and the wealth of life harbored there.

But the worsening climate crisis and the urgent need to transition away from fossil fuels has put deep-sea mining in the spotlight. Clean energy technologies like solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries contain critical minerals like nickel, lithium, cobalt, copper, and manganese, and concerns are growing over whether we’ll have enough of these materials to meet near-term net-zero goals. Some companies have pitched deep-sea mining as a solution. But would the risks be worth the potential rewards?

Into the deep

TMC’s mining process would involve collecting potato-size balls of rock, known as polymetallic nodules, that rest gently on top of the seafloor sediment and contain various critical minerals. These nodules have formed over millions of years, and they carpet vast swathes of the seabed. A large rover-like machine would be lowered from a ship down to the seafloor where it would gather the nodules and send them back up to the ship. (To give you a sense of depth, the area in the Pacific where TMC wants to mine, called the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), is a deep-sea abyssal plain some 2.5 miles down and is estimated to hold 21 billion tons of nodules.) The water and sediment that comes up with the nodules would then be pumped back into the ocean.

The company says it would pay “careful attention not to harm the integrity of the deep-ocean ecosystem” during this process and plans to use a real-time monitoring program that will enable it to “adapt, pause, and change . . . operations to stay within expected ecological thresholds.”

But the nodules themselves are an essential part of that ecosystem, and removing them would have consequences. Nodules are among the only hard surfaces in a vast plain of sludgy sediment, and serve as a habitat for many slow-growing and unique creatures, including sea sponges, corals, and octopuses. And the CCZ likely contains many thousands of species that have yet to be identified.

Research suggests that removing the nodules “would lead to a loss of food-web integrity and a significant depreciation of faunal biodiversity.” Disturbing the ocean food web could have cascading effects, putting many fish populations at risk and threatening the livelihoods and food security of millions of people. (The Trump administration did not respond to request for comment by the time of publication.)

There are other concerns. The mere presence of the rover itself in an environment that has remained untouched for millennia would likely disturb its living organisms, most of which exist in the top 2 inches of sediment, explains Oliver Ashford, a marine biologist with the World Resources Institute’s Ocean Program. “The organisms there aren’t really adapted to rapidly changing currents and being thrown around and disrupted,” he says. “They’re quite delicate organisms normally. So the physical interaction with that machine might cause death.” A recent study published in the journal Nature found that life at a small deep-sea mining test site in the CCZ is still recovering four decades after the tests were conducted.

The creatures that aren’t physically disturbed by the rover could be harmed by changes in temperature, light, and sound. The activity could stir up large plumes of sediment that get picked up by ocean currents and spread across hundreds of miles, smothering and starving sponges and coral and disrupting fishing activities. There’s even some concern that mining could interfere with the ocean’s natural ability to sequester carbon and produce oxygen, further harming the Earth’s climate. TMC doesn’t deny that deep-sea mining comes with environmental risks, but says “the clean energy transition will require trade-offs.”

Who’s in charge around here?

The U.N.’s International Seabed Authority is responsible for setting environmental and financial regulations for the nascent deep-sea mining industry, but has yet to do so even after years of deliberations. “They’re developing regulations from scratch for an industry that could potentially have a large environmental impact,” Ashford says of the ISA. “I feel like it’s a process that shouldn’t be rushed.” But the sluggish pace of this rulemaking has frustrated some mining firms, including TMC, that are tired of waiting.

Technically the United States doesn’t have to wait for the ISA to give mining the go-ahead because it never ratified the UN Law of the Sea, the 1994 treaty that put the ISA in charge of seabed mining. This is why TMC has come knocking on Trump’s door. The company promises “a massive and rapid injection of metals” into the U.S. if it’s allowed to mine the seabed. This is important because demand for critical minerals is expected to more than double by 2030 and triple by 2040 as clean energy technology advances.

While mineral reserves are abundant on land, production tends to be concentrated in a handful of countries—in China especially—which makes the supply chain unreliable. In the U.S., for example, more than 80% of critical minerals are imported. And heightened trade tensions will further tighten supply: China recently restricted exports of seven rare earth elements in response to Trump’s tariffs on Chinese goods. Lack of investment has also made it difficult to rapidly scale up mineral production. Deep-sea mining, therefore, is “a path to making real progress toward solving our supply chain problem,” TMC says in a promotional video.

TMC also argues that deep-sea mining would be less harmful for the environment than terrestrial mining activities. It’s true that land mining contributes to pollution, resource depletion, and damage to biodiversity. “Mining, by its nature, is not a zero-harm activity. It poses significant risks to the environment and local communities,” writes Melissa Barbanell at the World Resources Institute. But it’s not clear that deep-sea mining would be more sustainable than land mining, and TMC admits that seabed mining is unlikely to replace land mining anytime soon.

Peering into the future

Some groups predict that rapid technological advances, improved recycling methods, and robust circular economies would be enough to help us use the minerals we have more efficiently, eliminating the need for deep-sea mining altogether. “Future mineral demand can be met without deep seabed mining,” declared the World Wildlife Fund in a report finding that innovations could curb demand for critical minerals by 20% to 58% by 2050.

As with so many new technologies, figuring out whether deep-sea mining is a good idea or a bad one isn’t straightforward. A paper published in the journal Ocean Sustainability a few years ago tried to look at the question through an economic lens. The researchers wanted to know: Of all the key stakeholders—from mining companies to governments to humanity at large—who really benefits from deep-sea mining, and by how much? “Our conclusion was that only the commercial mining companies are likely to get some profit, and it’s not much,” says Ussif Rashid Sumaila, a professor of ocean and fisheries economics at the University of British Columbia, and lead author on the paper.

The analysis found that revenues would likely be huge for deep-sea mining companies in the first few years while demand for minerals is high, but would drop off as the market is flooded and prices come down. Combine this with high operational costs and the threat of numerous expensive lawsuits, and the long-term viability of deep-sea mining looks tenuous. Some companies, like the Norwegian firm Loke Marine Minerals, have already gone bust due to funding troubles.

As for another key stakeholder—nature—Sumaila’s paper concluded that the costs of managing environmental damage caused by deep-sea mining will likely be astronomical. “Look,” he says, “sometimes you just have to leave things alone.”

![How to Find Low-Competition Keywords with Semrush [Super Easy]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/73/62/7362f16fb9e460b6d58ccc09b4a048b6/how-to-find-low-competition-keywords-sm.png)