China’s rare earth minerals power the modern world. Banning their export could destroy it

“China has already won the materials war.” Andrew Barron, one of the top materials experts on the planet, didn’t mince words when I interviewed him for a documentary on the dangers of our civilization’s dependency on China’s quasi-monopoly of rare earth minerals. If the world does not stop depending on China’s supply of rare earths, he warned two years ago, we could face an economic collapse in just a few decades. It sounds like a dystopian sci-fi movie, but this potentially catastrophic scenario began this week for the United States, when Xi Jinping’s government issued an immediate suspension of rare earth mineral and magnet exports, retaliating against President Trump’s trade policies. This isn’t just a supply chain hiccup—it’s a geopolitical detonation with direct consequences to the economy and all of our lives. China controls 69% of global rare earth mining and a staggering 85–90% of refining and processing, the complex alchemy that transforms raw ore into the materials that make absolutely everything that is crucial to our everyday lives, from your electric toothbrush to phone to computer to your electric car to the servers that make everything run. If it beeps, it depends on these minerals. And without China’s processing dominance, even minerals mined elsewhere are functionally useless. Now export licenses have been frozen on samarium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, lutetium, scandium, and yttrium, which are used to make the powerful magnets in many of the electric motors that are crucial in electric vehicles, robots, satellites, missiles, and drones. Beijing has also banned the export of the magnets themselves (they produce 90% of the rare earth magnets globally). And this is just a warning shot with very serious effects for big industries, especially the defense sector. If China wanted, it could also ban lithium exports (it controls approximately 67% of the world’s refining capacity) and batteries, of which it controls (80% of the world’s production). Right now, you can bet that many executives in industries from Detroit to Dresden are staring into the abyss thinking about the possibility of further escalation. How did we get here? This chokehold isn’t accidental. For decades, China has weaponized state subsidies, environmental deregulation, and strategic overseas investments to corner the market. As the U.S. shuttered Nevada’s Mountain Pass in 2002, its last major rare earth mine (later revived in 2017 by MP Materials, the U.S.’s only rare earth materials producer), China secured major rare earth mineral mines all around the world, from Chile and Bolivia’s lithium to cobalt in the Democratic Republic of Congo. “They’ve essentially monopolized the entire [rare earth minerals] supply chain,” Barron says. China decides who gets what—and when. Even partnerships with allies will falter if Jinping decided to escalate the crisis. Australia mines lithium, but lacks refining capacity; South Korea’s LG Chem produces batteries but depends on Chinese graphite. And there will be a huge problem with magnets, too: Neodymium magnets are in almost every machine around us. Without it, everything from cars to wind turbines stop working. Beijing controls 80% of this metal. The rare earth domino effect So, yes, this export freeze will disrupt the U.S. economy. But further escalation would practically halt everything. in a big way. Here’s how: 1. Automotive Japanese firms like Toyota and Honda stockpile rare earth magnets, but most global automakers lack reserves. A six-month magnet shortage could halt 80% of global EV production, an estimated 5.6 million vehicles lost, costing automakers about $150 billion in lost revenue. Hybrid vehicles, dependent on lanthanum in nickel-metal hydride batteries, face similar delays. These setbacks risk prolonging fossil fuel reliance and derailing climate goals. As for batteries, here in the U.S., Tesla, Ford, and GM rely on Chinese-refined lithium or Chinese-made batteries, while 80% of the world’s cobalt—critical for high-performance batteries—is controlled by Chinese companies. As Ho-Yin Mak, associate professor in Operations & Information Management at Georgetown University, notes: “You can’t build an EV ecosystem overnight when China owns the blueprint.” 2. Tech & semiconductors Apple’s iPhone depends on batteries for power and neodymium for haptic feedback and speakers, just like many gadgets you have in your home. Western Digital and Seagate require rare earths for hard drive read/write heads—critical for data storage. And let’s not forget chips: semiconductor manufacturing, reliant on europium and terbium for etching. 3. Renewable energy To give you an idea on how dependent we are on Chinese rare earths for energy, a typical 3-megawatt GE wind turbine requires 2 tons of rare earths. The U.S. aims to deploy 30 GW of offshore wind by 2030, but a magnet shortage could delay 50% of planned capacity. Existing turbines will fac

“China has already won the materials war.”

Andrew Barron, one of the top materials experts on the planet, didn’t mince words when I interviewed him for a documentary on the dangers of our civilization’s dependency on China’s quasi-monopoly of rare earth minerals. If the world does not stop depending on China’s supply of rare earths, he warned two years ago, we could face an economic collapse in just a few decades.

It sounds like a dystopian sci-fi movie, but this potentially catastrophic scenario began this week for the United States, when Xi Jinping’s government issued an immediate suspension of rare earth mineral and magnet exports, retaliating against President Trump’s trade policies.

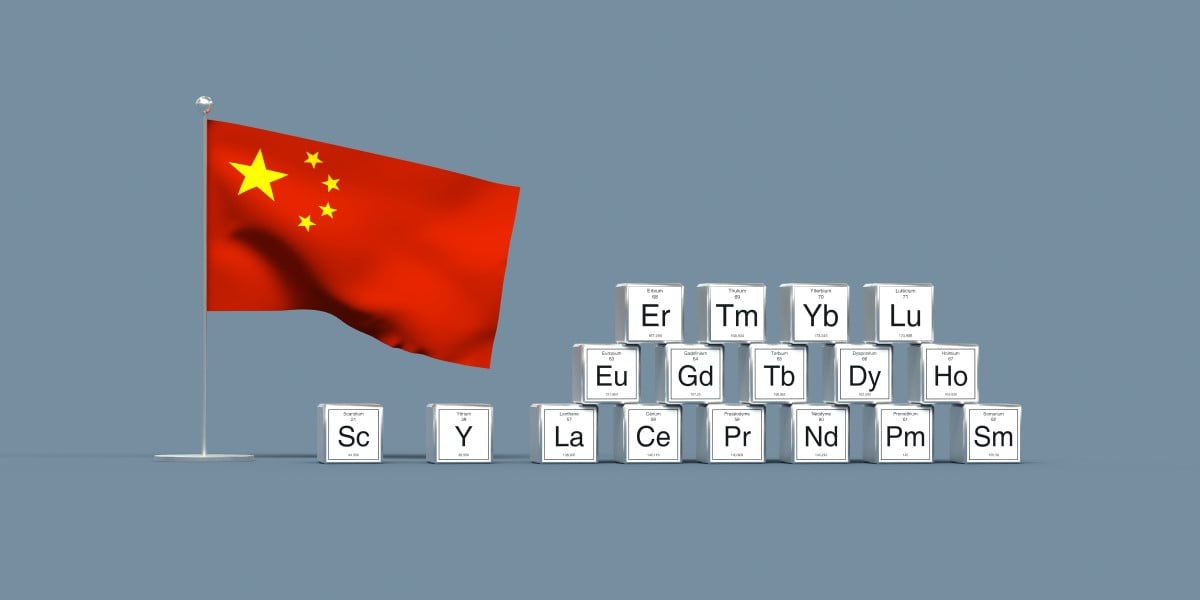

This isn’t just a supply chain hiccup—it’s a geopolitical detonation with direct consequences to the economy and all of our lives. China controls 69% of global rare earth mining and a staggering 85–90% of refining and processing, the complex alchemy that transforms raw ore into the materials that make absolutely everything that is crucial to our everyday lives, from your electric toothbrush to phone to computer to your electric car to the servers that make everything run. If it beeps, it depends on these minerals. And without China’s processing dominance, even minerals mined elsewhere are functionally useless.

Now export licenses have been frozen on samarium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, lutetium, scandium, and yttrium, which are used to make the powerful magnets in many of the electric motors that are crucial in electric vehicles, robots, satellites, missiles, and drones. Beijing has also banned the export of the magnets themselves (they produce 90% of the rare earth magnets globally).

And this is just a warning shot with very serious effects for big industries, especially the defense sector. If China wanted, it could also ban lithium exports (it controls approximately 67% of the world’s refining capacity) and batteries, of which it controls (80% of the world’s production). Right now, you can bet that many executives in industries from Detroit to Dresden are staring into the abyss thinking about the possibility of further escalation.

How did we get here?

This chokehold isn’t accidental. For decades, China has weaponized state subsidies, environmental deregulation, and strategic overseas investments to corner the market. As the U.S. shuttered Nevada’s Mountain Pass in 2002, its last major rare earth mine (later revived in 2017 by MP Materials, the U.S.’s only rare earth materials producer), China secured major rare earth mineral mines all around the world, from Chile and Bolivia’s lithium to cobalt in the Democratic Republic of Congo. “They’ve essentially monopolized the entire [rare earth minerals] supply chain,” Barron says.

China decides who gets what—and when. Even partnerships with allies will falter if Jinping decided to escalate the crisis. Australia mines lithium, but lacks refining capacity; South Korea’s LG Chem produces batteries but depends on Chinese graphite. And there will be a huge problem with magnets, too: Neodymium magnets are in almost every machine around us. Without it, everything from cars to wind turbines stop working. Beijing controls 80% of this metal.

The rare earth domino effect

So, yes, this export freeze will disrupt the U.S. economy. But further escalation would practically halt everything. in a big way. Here’s how:

1. Automotive

Japanese firms like Toyota and Honda stockpile rare earth magnets, but most global automakers lack reserves. A six-month magnet shortage could halt 80% of global EV production, an estimated 5.6 million vehicles lost, costing automakers about $150 billion in lost revenue. Hybrid vehicles, dependent on lanthanum in nickel-metal hydride batteries, face similar delays. These setbacks risk prolonging fossil fuel reliance and derailing climate goals.

As for batteries, here in the U.S., Tesla, Ford, and GM rely on Chinese-refined lithium or Chinese-made batteries, while 80% of the world’s cobalt—critical for high-performance batteries—is controlled by Chinese companies. As Ho-Yin Mak, associate professor in Operations & Information Management at Georgetown University, notes: “You can’t build an EV ecosystem overnight when China owns the blueprint.”

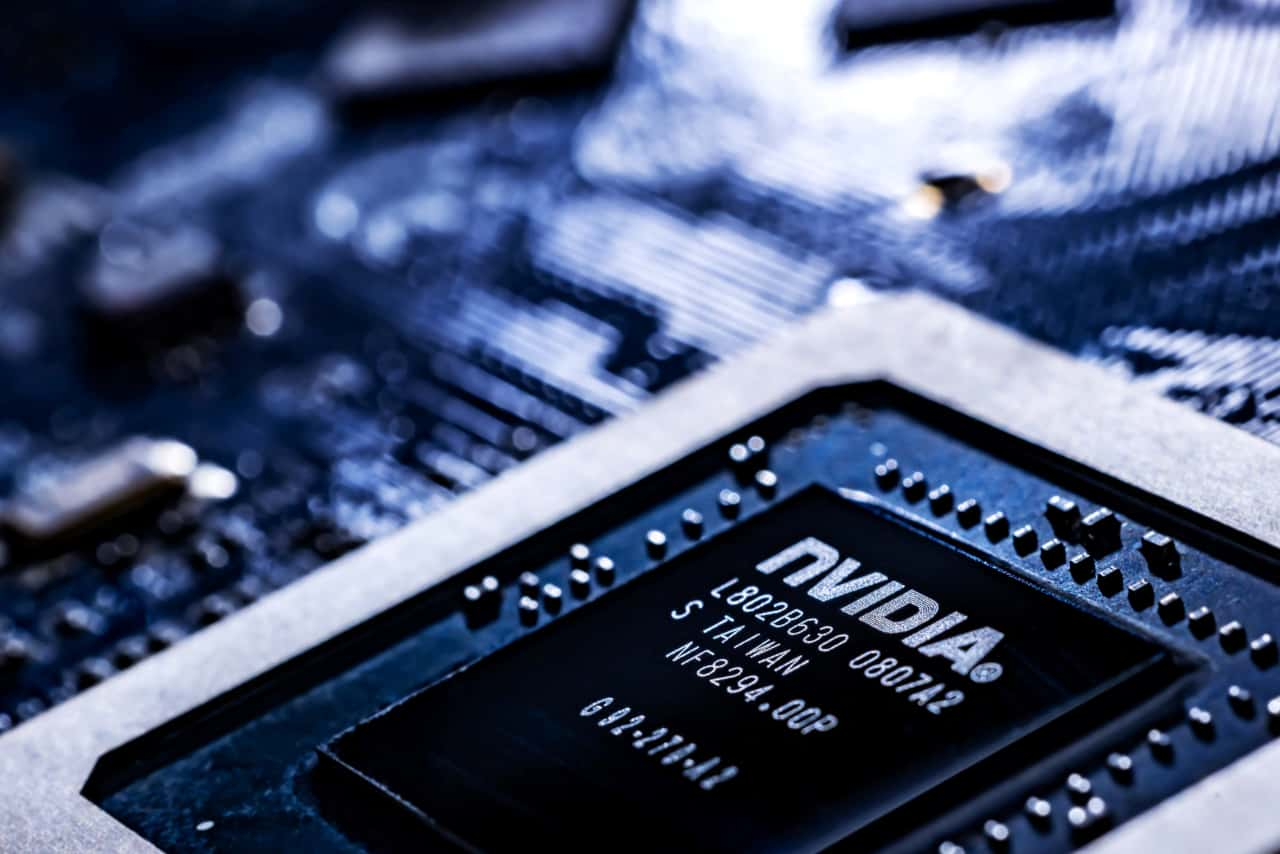

2. Tech & semiconductors

Apple’s iPhone depends on batteries for power and neodymium for haptic feedback and speakers, just like many gadgets you have in your home. Western Digital and Seagate require rare earths for hard drive read/write heads—critical for data storage. And let’s not forget chips: semiconductor manufacturing, reliant on europium and terbium for etching.

3. Renewable energy

To give you an idea on how dependent we are on Chinese rare earths for energy, a typical 3-megawatt GE wind turbine requires 2 tons of rare earths. The U.S. aims to deploy 30 GW of offshore wind by 2030, but a magnet shortage could delay 50% of planned capacity. Existing turbines will face maintenance crises. Replacement parts for aging installations, like those in Texas’s onshore farms, could take years to source. Solar panel production, dependent on terbium and europium for photovoltaic cells, faces similar bottlenecks.

4. Defense

This is where the current ban really impacts the U.S. The Pentagon will definitely not like the halt. It has warned that delays in sourcing these materials could compromise national security. Almost every airplane and complex weapons systems out there depend on rare earth minerals. As Gracelin Baskaran and Meredith Schwartz write for the Center for Strategic and International Studies, the rare earth elements banned by China “are crucial for a range of defense technologies, including F-35 fighter jets, Virginia- and Columbia-class submarines, Tomahawk missiles, radar systems, Predator unmanned aerial vehicles, and the Joint Direct Attack Munition series of smart bombs.” They note that one F-35 fighter jet alone “uses over 900 pounds of these materials, the Arleigh Burke-class DDG-51 destroyer requires approximately 5,200 pounds, and a Virginia-class submarine uses around 9,200 pounds.” These three weapons are cornerstones of the U.S. superiority.

5. Healthcare

Siemens Healthineers’ MRI machines rely on samarium-cobalt magnets for imaging. Shortages will delay new machines and compromise the supply of replacement parts for maintenance. This will in return spike costs all across the healthcare system, delay diagnostics, and strain healthcare systems.

6. Consumer goods

From headphones like your Apple AirPods or Bose’s noise-canceling headphones to Philips Sonicare toothbrushes, gadets all use rare earth-dependent motors. Even low-cost electronics, like Walmart earbuds, are at risk.

7. Heavy industry

ABB’s industrial robots and Fanuc’s CNC machines require rare earths for precision. A shortage could disrupt global manufacturing, triggering layoffs and inflation.

No escape

The worst news is that the U.S. has no quick fixes for any of this. MP Materials’ stock skyrocketed yesterday because it’s the only company that has some capacity to process these rare earth materials in the U.S. It launched a magnet production facility this year in Texas, but that’s a Band-Aid compared to the needs the industry faces. As Baskaran and Schwartz note, “MP Materials will only be producing 1,000 tons of neodymium-boron-iron (NdFeB) magnets by the end of 2025. That is less than 1 percent of the 138,000 tons of NdFeB magnets China produced in 2018.”

Still, the fact remains that the entire U.S. defense industry depends on this company right now. In 2022, the Pentagon awarded MP Materials a $35M contract to build new rare earth minerals processing facilities, but now it will most likely pour a lot more than that into it to accelerate its growth. It’s the only hope to provide the Pentagon’s military complex and the EV car industry with enough material any time soon. According to analysts, the company is “up to the challenge.”

If China decided to further tighten the screws on the U.S., it is in an even worse position. The Trump administration could expedite partnerships with Korean battery makers like LG Chem, but scaling production takes years. And again, South Korea depends on China, too, like everyone else. You may think that the lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) batteries that Tesla uses will help because they avoid cobalt. But lithium is also controlled by China, and just guess where Tesla’s batteries are made? Shanghai! So close, but no cigar, folks. China’s CATL produces 75% of global LFP batteries.

Now, the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 allocated $3.16 billion for battery supply chains, but as we already know, the U.S. lacks refining infrastructure. And domestic mining of these minerals faces hurdles in the U.S. Nevada lithium deposits faced local opposition and only got approved in October 2024. Meanwhile, Minnesota cobalt remains untapped. Trump may accelerate all this, but it will take years to make it happen. Even if he steals all the rare earth minerals from Ukraine, those deposits are also largely unexploited. And, again, refining is controlled by China. Even if the U.S. could secure all the raw minerals it needs, building refineries here to reach the level will take years.

And forget about recycling. Current systems recover less than 5% of lithium. As Solomon Asfaw, a battery expert at Finland’s LUT University, told me in a video interview: “Efficiency needs to hit 95% to offset demand. Otherwise, we’re just delaying collapse.”

In other words: There’s no short- or medium-term way around this, which makes it even more surprising that Trump’s administration didn’t see this coming. As Baskaran and Schwartz point out, everyone knew China showed no qualms in weaponizing rare earths. It started in 2010, when it banned exports to Japan over a fishing dispute. Between 2023 and 2025, it already imposed export restrictions on strategic materials like gallium, germanium, antimony, graphite, and tungsten to the U.S. It was only logical to assume that, in a trade war, Beijing was going to do exactly what is has done.

The U.S. can invest billions in mines, refineries, and labs, but, for a few years, our economy will remain a hostage to China. Barron was right. The materials war is over before it even started. China won. Now comes the reckoning.

![How to Find Low-Competition Keywords with Semrush [Super Easy]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/73/62/7362f16fb9e460b6d58ccc09b4a048b6/how-to-find-low-competition-keywords-sm.png)