Can the Trump-Musk bromance survive the tariff trade wars?

When Donald Trump announced that Elon Musk would be joining the government as an adviser and head of the quasi-governmental Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), there was skepticism about how long the relationship between the two would last. Experts predicted that the SpaceX founder wouldn’t like playing second fiddle to the former Apprentice star. As Trump himself put it in his 1987 business-advice book The Art of the Deal, “One of the problems when you become successful is that jealousy and envy inevitably follow.” But it’s not success that appears to have driven the most serious wedge between the two businessmen. It’s failure, and the catastrophic fallout from Trump’s implementation of tariffs that has triggered a global trade war—a decision that Trump has hit pause on, temporarily forestalling for 90 days reciprocal tariffs on all countries except China. It’s a trade war that Musk never wanted. The Washington Post reports that Musk lobbied Trump directly, though unsuccessfully, to not levy tariffs. And as those tariffs decimated U.S. stock markets, in a series of gobsmacking posts on X this week Musk has dubbed White House trade tsar Peter Navarro “Peter Retarrdo,” a “moron,” and “dumber than a sack of bricks.” While the name-calling has been limited to Navarro, the criticism is fundamentally pointed at Trump’s most signature policy to date. Musk’s brother, Kimbal, has quote tweeted Trump while adding negative comments about his tariff decisions. “Mmm.. Celebrating causing China’s stock market to go down, by causing our own stock market to go down? Maybe this is why Trump brought back the R word.” It’s not clear whether he is referring to the risk of a recession, or echoing his brother’s comments about Navarro. Karoline Leavitt, Trump’s press secretary, said on April 8 about the Navarro-Musk spat: “These are obviously two individuals who have very different views on trade and tariffs. Boys will be boys and we will let their public sparring continue.” A clash of titanic egos Not everyone is convinced that’s all there is to it. It could be the first major public blowup between two titanic egos who were always going to struggle to coexist. That Musk and Trump would clash on the issue isn’t surprising. China was a healthy market for Musk’s electric vehicle company, Tesla, and Trump’s 125% tariffs on goods from China will likely harm that business relationship. “Musk has a big financial relationship with China, which is not happy with tariffs,” says Steven Hassan, author of The Cult of Trump. Navarro’s expertise is more rooted in academia and therefore takes a different approach to Musk’s, explains Steven Buckley, a lecturer in digital media sociology at City, University of London, who specializes in U.S. politics. “Fundamentally I don’t believe anyone in Trump’s Cabinet actually has a good understanding of the impact of tariffs and how the wider global economy works. However, Musk actually experiences the direct impact of them on his businesses, and so regardless of whatever good trade policy would be, he knows that this isn’t it—for him at least.” Trump, for his part, is not exactly jumping to tariff architect Navarro’s defense. “Despite Trump’s press secretary saying this spat is just boys being boys, it’s clear that Trump is fine to let these spats occur out in the open as they serve as a convenient distraction from any disagreement those in the administration may have with [him],” Buckley adds. It’s notable that Musk has held his tongue publicly about Trump, instead attacking individuals linked to the plan lower down the White House pecking order, while outliers like his brother criticize the president’s tariffs. Attacks on Navarro can also be excused away by Trump as not targeting him or his decision-making—important, given the president can be stuck in his ways and refuses to back down on his decisions, even when presented with evidence that he’s wrong, as shown by a vignette in Bob Woodward’s recent book about first-term economic adviser Gary Cohn telling Trump Americans don’t want to do manual labor. “Navarro acts as a useful scapegoat so that when the damage these tariffs cause starts being felt by consumers Trump can blame him for his advice,” Buckley says. In the end, the tempestuous tweets were to be expected. Both Trump and Musk (who, in attacking Navarro, has attacked Trump and his policy by proxy) have built their reputations being abrasive and shooting from the hip on social media. The White House has sought to downplay the spat, releasing a statement about the brouhaha, saying: “Whatever. We are the most transparent administration in history, expressing our disagreements in public.” Says Buckley: “It’s clear that Trump and those in his administration are immune to embarrassment, and so these ugly public arguments only serve as a media story about political personalities at war with one another.”

When Donald Trump announced that Elon Musk would be joining the government as an adviser and head of the quasi-governmental Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), there was skepticism about how long the relationship between the two would last. Experts predicted that the SpaceX founder wouldn’t like playing second fiddle to the former Apprentice star.

As Trump himself put it in his 1987 business-advice book The Art of the Deal, “One of the problems when you become successful is that jealousy and envy inevitably follow.”

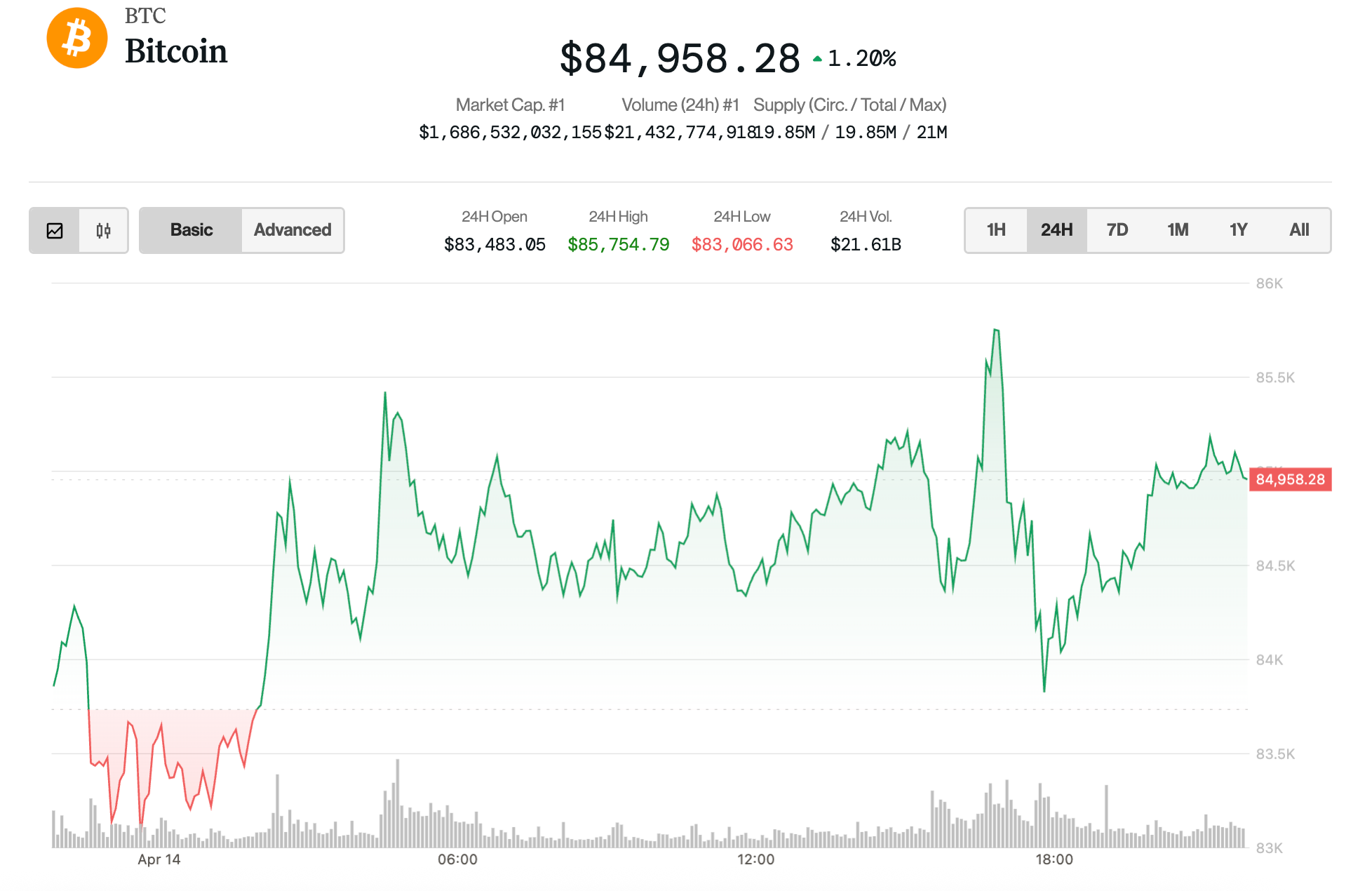

But it’s not success that appears to have driven the most serious wedge between the two businessmen. It’s failure, and the catastrophic fallout from Trump’s implementation of tariffs that has triggered a global trade war—a decision that Trump has hit pause on, temporarily forestalling for 90 days reciprocal tariffs on all countries except China.

It’s a trade war that Musk never wanted. The Washington Post reports that Musk lobbied Trump directly, though unsuccessfully, to not levy tariffs. And as those tariffs decimated U.S. stock markets, in a series of gobsmacking posts on X this week Musk has dubbed White House trade tsar Peter Navarro “Peter Retarrdo,” a “moron,” and “dumber than a sack of bricks.” While the name-calling has been limited to Navarro, the criticism is fundamentally pointed at Trump’s most signature policy to date.

Musk’s brother, Kimbal, has quote tweeted Trump while adding negative comments about his tariff decisions. “Mmm.. Celebrating causing China’s stock market to go down, by causing our own stock market to go down? Maybe this is why Trump brought back the R word.” It’s not clear whether he is referring to the risk of a recession, or echoing his brother’s comments about Navarro.

Karoline Leavitt, Trump’s press secretary, said on April 8 about the Navarro-Musk spat: “These are obviously two individuals who have very different views on trade and tariffs. Boys will be boys and we will let their public sparring continue.”

A clash of titanic egos

Not everyone is convinced that’s all there is to it. It could be the first major public blowup between two titanic egos who were always going to struggle to coexist.

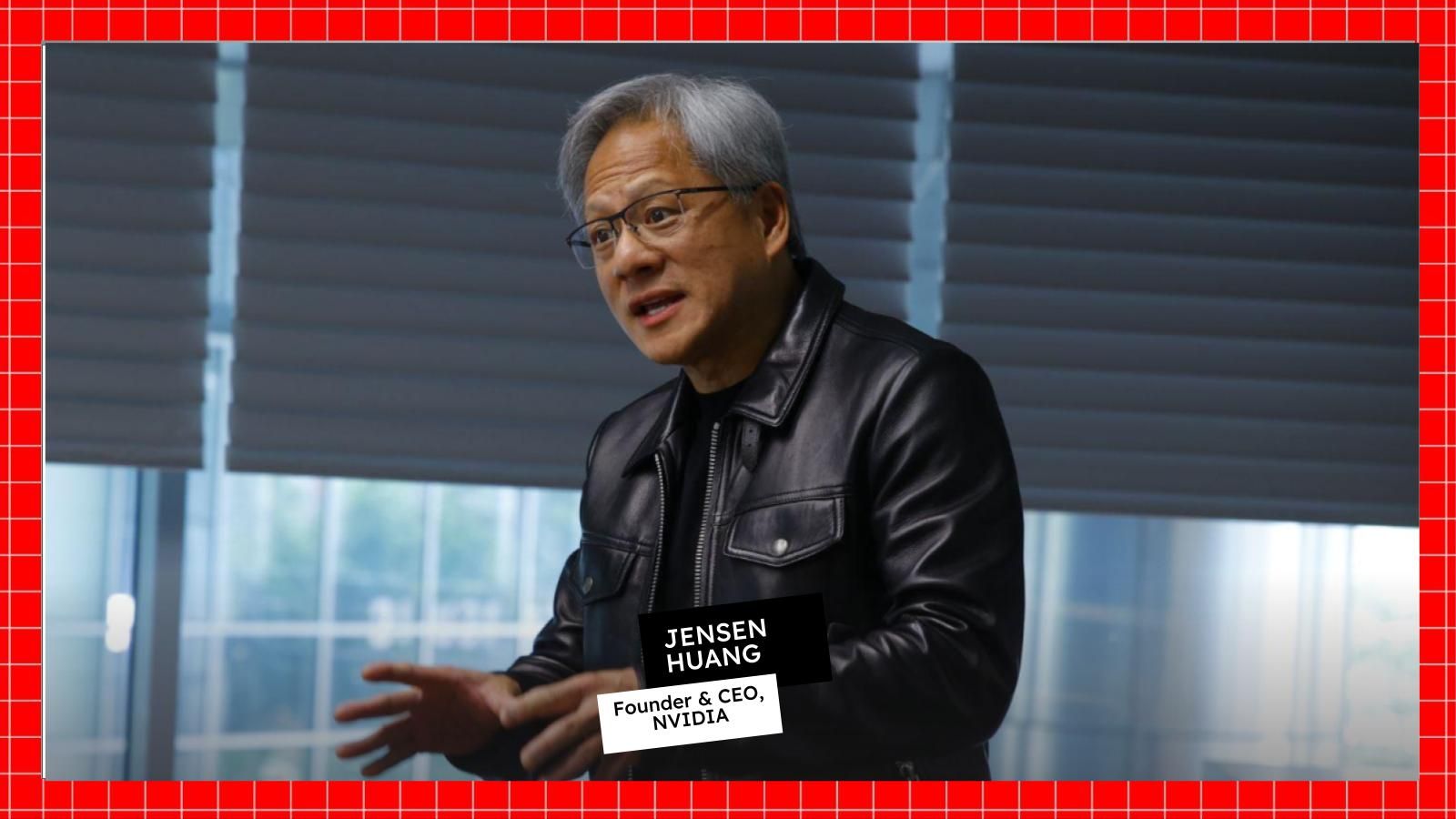

That Musk and Trump would clash on the issue isn’t surprising. China was a healthy market for Musk’s electric vehicle company, Tesla, and Trump’s 125% tariffs on goods from China will likely harm that business relationship. “Musk has a big financial relationship with China, which is not happy with tariffs,” says Steven Hassan, author of The Cult of Trump.

Navarro’s expertise is more rooted in academia and therefore takes a different approach to Musk’s, explains Steven Buckley, a lecturer in digital media sociology at City, University of London, who specializes in U.S. politics. “Fundamentally I don’t believe anyone in Trump’s Cabinet actually has a good understanding of the impact of tariffs and how the wider global economy works. However, Musk actually experiences the direct impact of them on his businesses, and so regardless of whatever good trade policy would be, he knows that this isn’t it—for him at least.”

Trump, for his part, is not exactly jumping to tariff architect Navarro’s defense. “Despite Trump’s press secretary saying this spat is just boys being boys, it’s clear that Trump is fine to let these spats occur out in the open as they serve as a convenient distraction from any disagreement those in the administration may have with [him],” Buckley adds. It’s notable that Musk has held his tongue publicly about Trump, instead attacking individuals linked to the plan lower down the White House pecking order, while outliers like his brother criticize the president’s tariffs.

Attacks on Navarro can also be excused away by Trump as not targeting him or his decision-making—important, given the president can be stuck in his ways and refuses to back down on his decisions, even when presented with evidence that he’s wrong, as shown by a vignette in Bob Woodward’s recent book about first-term economic adviser Gary Cohn telling Trump Americans don’t want to do manual labor. “Navarro acts as a useful scapegoat so that when the damage these tariffs cause starts being felt by consumers Trump can blame him for his advice,” Buckley says.

In the end, the tempestuous tweets were to be expected. Both Trump and Musk (who, in attacking Navarro, has attacked Trump and his policy by proxy) have built their reputations being abrasive and shooting from the hip on social media. The White House has sought to downplay the spat, releasing a statement about the brouhaha, saying: “Whatever. We are the most transparent administration in history, expressing our disagreements in public.”

Says Buckley: “It’s clear that Trump and those in his administration are immune to embarrassment, and so these ugly public arguments only serve as a media story about political personalities at war with one another.”

![How to Find Low-Competition Keywords with Semrush [Super Easy]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/73/62/7362f16fb9e460b6d58ccc09b4a048b6/how-to-find-low-competition-keywords-sm.png)