California’s location data privacy bill aims to reshape digital consent

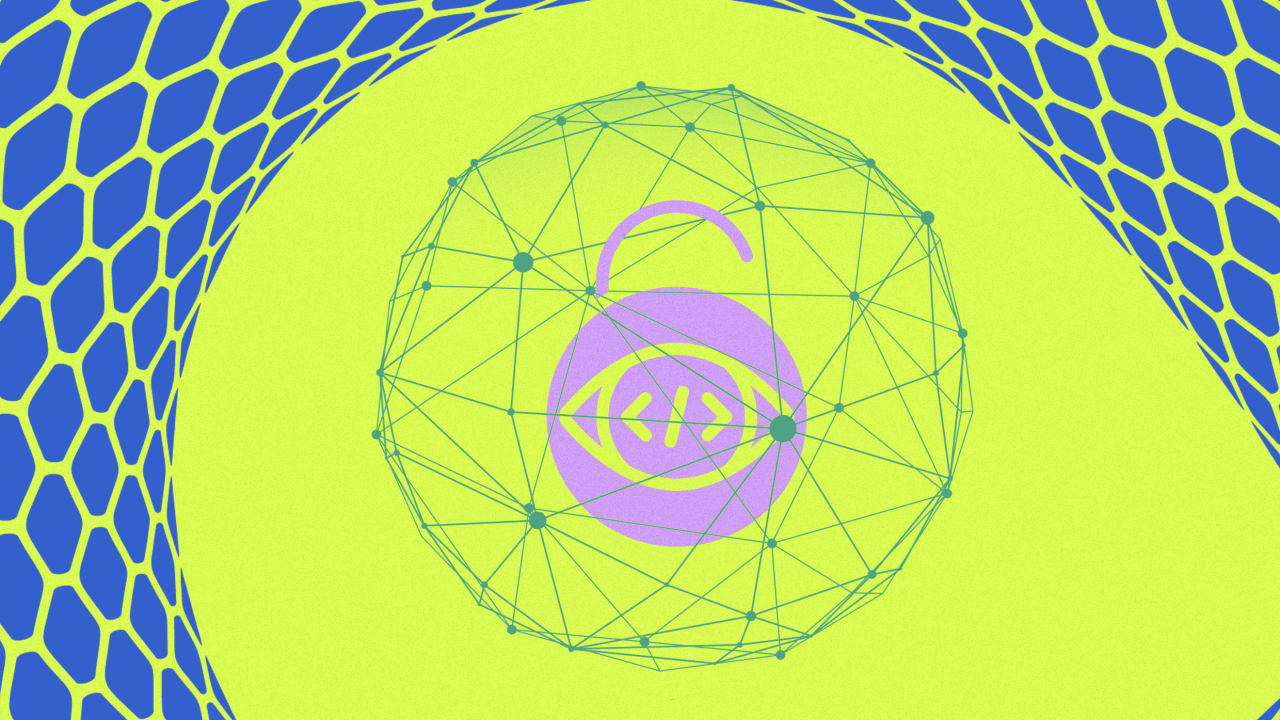

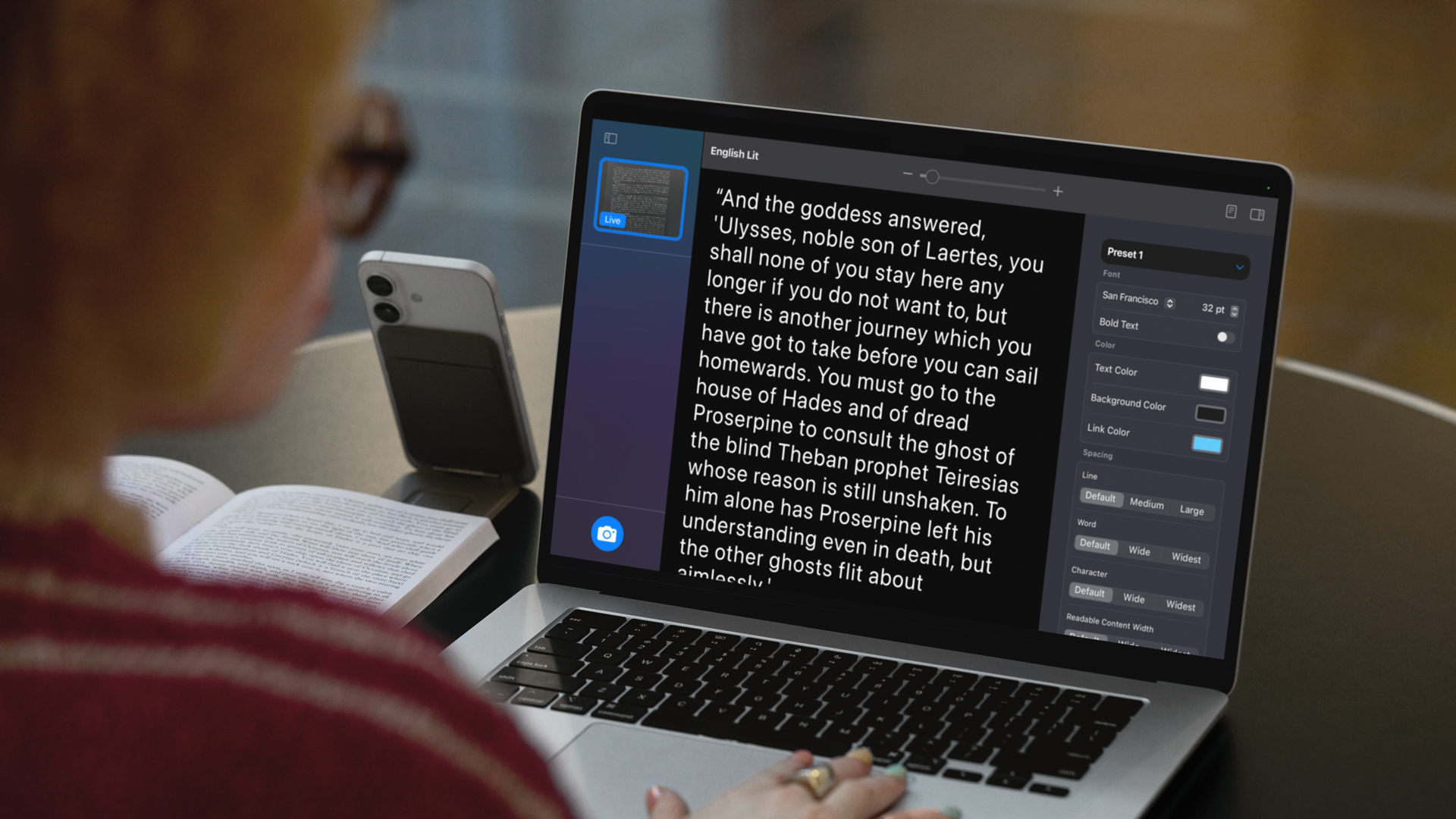

Amid the ongoing evolution of digital privacy laws, one California proposal is drawing heightened attention from legal scholars, technologists, and privacy advocates. Assembly Bill 1355, while narrower in scope than landmark legislation like 2018’s California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA)—which established sweeping rights for consumers to know, delete, and opt out of the sale of their personal information—could become a pivotal effort to rein in the unchecked collection and use of personal geolocation data. The premise of the bill (which is currently undergoing analysis within the appropriations committee) is straightforward yet bold in the American legal landscape: Companies must obtain clear, opt-in consent before collecting or sharing users’ precise location data. They must also disclose exactly what data they gather, why they gather it, and who receives it. At a glance, this seems like a logical privacy upgrade. But beneath the surface, it questions the very structure of an industry built on the quiet extraction and monetization of personal information. “We’re really trying to help regulate the use of your geolocation data,” says the bill’s author, Democratic Assemblymember Chris Ward, who represents California’s 78th district, which covers parts of San Diego and surrounding areas. “You should not be able to sell, rent, trade, or lease anybody’s location information to third parties, because nobody signed up for that.” Among types of personal information, location data is especially sensitive. It reveals where people live, work, worship, protest, and seek medical care. It can expose routines, relationships, and vulnerabilities. As stories continue to surface about apps selling location data to brokers, government workers, and even bounty hunters, the conversation has expanded. What was once a debate about privacy has increasingly become a concern over how the exposure of this data infringes upon fundamental civil liberties. “Geolocation is very revealing,” says Justin Brookman, the director of technology policy at Consumer Reports, which supported the legislation. “It tells a lot about you, and it also can be a public safety issue if it gets into the wrong person’s hands.” For advocates of the new legislation, the concern goes beyond permission screens. It’s about control. When location data is collected silently and traded without oversight, people lose agency over how they move through the world—and who’s watching. A power imbalance at the heart of location tracking To understand the urgency behind proposals like AB 1355, look at how current data practices operate. The core issue isn’t merely that companies collect information—it’s how relentlessly and opaquely they do so, often without real accountability. Consent, when obtained, is typically buried in lengthy and confusing policies. Meanwhile, data brokers operate with minimal regulation, assembling detailed behavioral profiles that may influence credit decisions, hiring, and insurance rates. Most people have little knowledge of who holds their data or how it’s used. For example, a fitness app might collect location data to track your exercise routes, but then sell that information to a data broker who assembles a profile for targeted advertising. This same information, in the wrong hands, could also be used to stalk an individual, track their movements, or even determine their political affiliations. “A lot of people don’t have the luxury to know that they should opt out or that they need to know how to find out how to opt out,” Ward says. Equally troubling, Ward argues, is who benefits. The companies collecting and selling this data are driven by profit, not transparency. As scholar Shoshana Zuboff has argued, surveillance capitalism doesn’t thrive because users want personalized ads. It thrives because opting out is hard, if people even realize they’ve been opted in. AB 1355 proposes a shift: Consent to collect and share data must be given proactively, not retracted reactively. Rather than requiring users to hunt through settings, the burden would fall on companies to ask first. That rebalances the relationship between individuals and data collectors in a way that could set new norms beyond California. “It’s designed to take a lot of the burden off of consumers, so they don’t have to worry about micromanaging their privacy,” Brookman says. “Instead, they can just trust that when geolocation is shared, it’s being used for the reason they gave—if they agreed to it in the first place.” Industry groups, unsurprisingly, have raised concerns about operational impacts and innovation costs. In particular, critics warn that the burden on businesses could stifle innovation, particularly in sectors reliant on data-driven services. The California Chamber of Commerce wrote in an opposition letter that was shared with Fast Company that AB 1355 would create “confusion in operability for businesses” and impose costly new comp

Amid the ongoing evolution of digital privacy laws, one California proposal is drawing heightened attention from legal scholars, technologists, and privacy advocates. Assembly Bill 1355, while narrower in scope than landmark legislation like 2018’s California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA)—which established sweeping rights for consumers to know, delete, and opt out of the sale of their personal information—could become a pivotal effort to rein in the unchecked collection and use of personal geolocation data.

The premise of the bill (which is currently undergoing analysis within the appropriations committee) is straightforward yet bold in the American legal landscape: Companies must obtain clear, opt-in consent before collecting or sharing users’ precise location data. They must also disclose exactly what data they gather, why they gather it, and who receives it. At a glance, this seems like a logical privacy upgrade. But beneath the surface, it questions the very structure of an industry built on the quiet extraction and monetization of personal information.

“We’re really trying to help regulate the use of your geolocation data,” says the bill’s author, Democratic Assemblymember Chris Ward, who represents California’s 78th district, which covers parts of San Diego and surrounding areas. “You should not be able to sell, rent, trade, or lease anybody’s location information to third parties, because nobody signed up for that.”

Among types of personal information, location data is especially sensitive. It reveals where people live, work, worship, protest, and seek medical care. It can expose routines, relationships, and vulnerabilities. As stories continue to surface about apps selling location data to brokers, government workers, and even bounty hunters, the conversation has expanded. What was once a debate about privacy has increasingly become a concern over how the exposure of this data infringes upon fundamental civil liberties.

“Geolocation is very revealing,” says Justin Brookman, the director of technology policy at Consumer Reports, which supported the legislation. “It tells a lot about you, and it also can be a public safety issue if it gets into the wrong person’s hands.”

For advocates of the new legislation, the concern goes beyond permission screens. It’s about control. When location data is collected silently and traded without oversight, people lose agency over how they move through the world—and who’s watching.

A power imbalance at the heart of location tracking

To understand the urgency behind proposals like AB 1355, look at how current data practices operate. The core issue isn’t merely that companies collect information—it’s how relentlessly and opaquely they do so, often without real accountability. Consent, when obtained, is typically buried in lengthy and confusing policies. Meanwhile, data brokers operate with minimal regulation, assembling detailed behavioral profiles that may influence credit decisions, hiring, and insurance rates. Most people have little knowledge of who holds their data or how it’s used.

For example, a fitness app might collect location data to track your exercise routes, but then sell that information to a data broker who assembles a profile for targeted advertising. This same information, in the wrong hands, could also be used to stalk an individual, track their movements, or even determine their political affiliations.

“A lot of people don’t have the luxury to know that they should opt out or that they need to know how to find out how to opt out,” Ward says.

Equally troubling, Ward argues, is who benefits. The companies collecting and selling this data are driven by profit, not transparency. As scholar Shoshana Zuboff has argued, surveillance capitalism doesn’t thrive because users want personalized ads. It thrives because opting out is hard, if people even realize they’ve been opted in.

AB 1355 proposes a shift: Consent to collect and share data must be given proactively, not retracted reactively. Rather than requiring users to hunt through settings, the burden would fall on companies to ask first. That rebalances the relationship between individuals and data collectors in a way that could set new norms beyond California.

“It’s designed to take a lot of the burden off of consumers, so they don’t have to worry about micromanaging their privacy,” Brookman says. “Instead, they can just trust that when geolocation is shared, it’s being used for the reason they gave—if they agreed to it in the first place.”

Industry groups, unsurprisingly, have raised concerns about operational impacts and innovation costs. In particular, critics warn that the burden on businesses could stifle innovation, particularly in sectors reliant on data-driven services. The California Chamber of Commerce wrote in an opposition letter that was shared with Fast Company that AB 1355 would create “confusion in operability for businesses” and impose costly new compliance burdens. “Changing the rules has real economic cost to businesses and consumers,” the letter states. “Constantly doing so without adequate justification or need is irresponsible at best.”

A state bill with national stakes

The bill is part of a larger trend among states moving to fill the federal vacuum on privacy regulation. Since the CCPA’s passage, several states—including Virginia, Colorado, Connecticut, Utah, and Texas—have enacted their own data privacy laws. These measures vary in scope and strength, forming a state-by-state patchwork that complicates compliance but signals widespread concern. While most of these laws are general-purpose, a handful—such as recent efforts in Maryland and Massachusetts—have begun to zero in on specific risks like geolocation tracking, mirroring some of AB 1355’s core protections.

Broadly speaking, California’s evolving legal framework, from the CCPA to its 2020 update via the California Privacy Rights Act (which expanded privacy protections in part by establishing the California Privacy Protection Agency) and now AB 1355, often sets informal national standards. Many companies adopt California’s rules across the board simply to streamline operations.

That precedent-setting role isn’t lost on Ward. “I would hope that this could be model language that others could be able to adopt as well,” he says.

But location data adds urgency. In the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization in 2022, digital trails have taken on new weight. GPS data near abortion clinics or health apps tracking reproductive health are no longer abstract risks—they’re flashpoints in the national conversation about privacy, autonomy, and the role of technology in our most personal decisions.

![8 Marketing Principles You’ll Wish You Knew When You First Started [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/IrFUUizSVZJGsPem_wXXddL_nQGNvo8QImauGCOQCxo/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS84X21hcmtldGluZ19wcmluY2lwbGVzX2luZm8yLnBuZw==.webp)