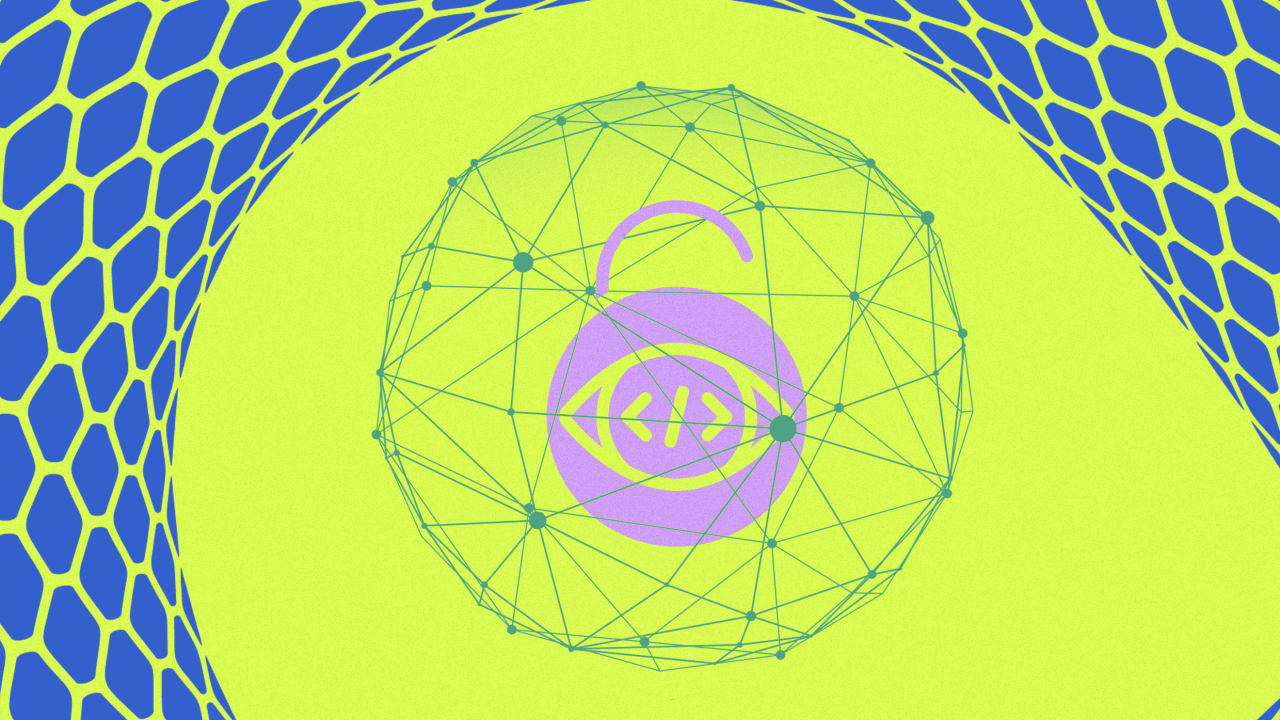

A US court just put ownership of CRISPR back in play

The CRISPR patents are back in play. On Monday, the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit said scientists Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier will get another chance to show they ought to own the key patents on what many consider the defining biotechnology invention of the 21st century. The pair shared a 2020…

The CRISPR patents are back in play.

On Monday, the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit said scientists Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier will get another chance to show they ought to own the key patents on what many consider the defining biotechnology invention of the 21st century.

The pair shared a 2020 Nobel Prize for developing the versatile gene-editing system, which is already being used to treat various genetic disorders, including sickle cell disease.

But when US patent rights were granted in 2014 to Feng Zhang of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, the decision set off a bitter dispute in which hundreds of millions of dollars—as well as scientific bragging rights—are at stake.

The new decision is a boost for the Nobelists, who had previously faced a string of demoralizing reversals over the patent rights in both the US and Europe.

“This goes to who was the first to invent, who has priority, and who is entitled to the broadest patents,” says Jacob Sherkow, a law professor at the University of Illinois.

He says there is now at least a chance that Doudna and Charpentier “could walk away as the clear winner.”

The CRISPR patent battle is among the most byzantine ever, putting the technology alongside the steam engine, the telephone, the lightbulb, and the laser among the most hotly contested inventions in history.

In 2012, Doudna and Charpentier were first to publish a description of a CRISPR gene editor that could be programmed to precisely cut DNA in a test tube. There’s no dispute about that.

However, the patent fight relates to the use of CRISPR to edit inside animal cells—like those of human beings. That’s considered a distinct invention, and one both sides say they were first to come up with that very same year.

In patent law, this moment is known as conception—the instant a lightbulb appears over an inventor’s head, revealing a definite and workable plan for how an invention is going to function.

In 2022, a specialized body called the Patent Trial and Appeal Board, or PTAB, decided that Doudna and Charpentier hadn’t fully conceived the invention because they initially encountered trouble getting their editor to work in fish and other species. Indeed, they had so much trouble that Zhang scooped them with a 2013 publication demonstrating he could use CRISPR to edit human cells.

The Nobelists appealed the finding, and yesterday the appeals court vacated it, saying the patent board applied the wrong standard and needs to reconsider the case.

According to the court, Doudna and Charpentier didn’t have to “know their invention would work” to get credit for conceiving it. What should matter more, the court said, is that it actually did work in the end.

In a statement, the University of California, Berkeley, applauded the call for a do-over.

“Today’s decision creates an opportunity for the PTAB to reevaluate the evidence under the correct legal standard and confirm what the rest of the world has recognized: that the Doudna and Charpentier team were the first to develop this groundbreaking technology for the world to share,” Jeff Lamken, one of Berkeley’s attorneys, said in the statement.

The Broad Institute posted a statement saying it is “confident” the appeals board “will again confirm Broad’s patents, because the underlying facts have not changed.”

The decision is likely to reopen the investigation into what was written in 13-year-old lab notebooks and whether Zhang based his research, in part, on what he learned from Doudna and Charpentier’s publications.

The case will now return to the patent board for a further look, although Sherkow says the court finding can also be appealed directly to the US Supreme Court.

![8 Marketing Principles You’ll Wish You Knew When You First Started [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/IrFUUizSVZJGsPem_wXXddL_nQGNvo8QImauGCOQCxo/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS84X21hcmtldGluZ19wcmluY2lwbGVzX2luZm8yLnBuZw==.webp)