Whose music is it anyway? OpenAI v top music labels sparks talks on fair use, licensing rights

With OpenAI facing a second backlash by top domestic music labels, legal experts and artists demand changes to existing copyright laws, along with concerns around licensing models and challenges around the human essence of music itself.

When French composer Olivier Messiaen composed his masterpiece, “Quartet for the End of Time” inside a concentration camp in Germany during World War II, the then 31-year-old relied on a prison guard who gave him a piece of paper to compose it. With three other musicians in the camp—a cellist, a violinist, and a clarinetist—he performed for thousands of prisoners and guards

While artificial intelligence has made music composition easier than ever before, can it replace the genius of an artist? And significantly, do existing copyright laws adequately protect the creative work done by humans?

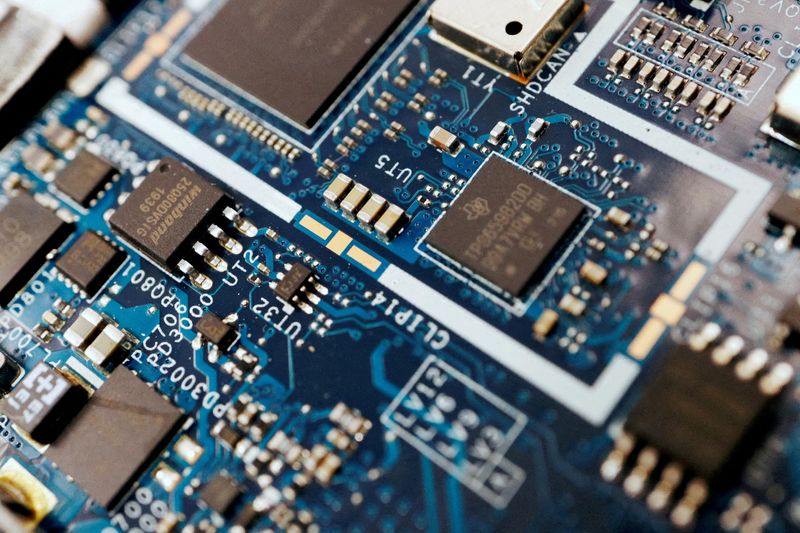

The Indian music industry's leading labels—including T-Series and Saregama—think not. By joining a high-profile lawsuit against , they have alleged that the company's AI models infringe on copyrights by scraping music and lyrics from the internet without authorisation.

Although it’s unclear if AI is an enabler or threat to the creative industries, legal experts and artists have voiced their concern about existing copyright law, which now demands further amendment.

Evaluation of AI-Large Language Model applications in final stage: Vaishnaw

The OpenAI lawsuit

Last month, leading top music labels such as T-Series, Saregama, and Sony Music (under the Indian Music Industry, IMI, association) moved to join a copyright lawsuit against OpenAI in New Delhi.

The argument is straightforward. They allege the ChatGPT-maker improperly used their copyrighted sound recordings to train AI models without authorisation. This isn’t the first time OpenAI has faced legal allegations in terms of copyright of creative content. The case originally began last November, when news agency ANI sued the company for using its news content to train ChatGPT without permission and it has since attracted interventions from publishers and media groups in India.

While the music industry’s involvement escalates the dispute, it also reflects broader fears about AI’s use of creative content.

It’s worth noting that the jurisdiction of the Indian court has been a point of contention–OpenAI argued that, as a US-based company with servers abroad, Indian courts “lack jurisdiction” over its operations. In response, the music companies assert that OpenAI’s substantial user base and operations in India (one of its largest markets) oblige it to comply with Indian copyright laws.

Kartik Dey, an advocate and patent attorney at the Supreme Court of India, Delhi High Court argues while OpenAI could claim that it uses publicly available data under fair use, the limitations of Indian copyright law and the company’s shift to a for-profit model—along with the potential market competition with original works—make this defense problematic.

“When OpenAI started in 2016, this defence may have been tenable (because it was a non-profit in the initial years) and has changed its structure through a subsidiary OPEN AI LP in 2019 which is presently valued at $157 billion by investors. It does not appear to be the case of Open AI that the trained outputs would not compete with the original copyright holder's work,” Dey tells YourStory.

This lawsuit also raises fundamental questions about how copyright law applies to AI training. The music companies claim that OpenAI’s model-training methods “involve extracting protected song lyrics, music compositions, and recordings without proper licensing or compensation”.

“OpenAI’s defence can be that it is using publicly available data which constitutes fair use, but Indian copyright allows fair use under certain conditions only, such as criticism, review, or research,” he adds.

Legal experts note that the purpose behind training AI is key – if general data is used just for training, it might be considered copyright infringement.

“There is no direct decision so far dealing with the aspect of AI vis-à-vis music. The decision of the case filed by ANI News against OpenAI would be relevant to figuring out the future trajectory of copyright law in the era of AI. That case is also pending adjudication before the Delhi High Court,” claims Srish Mishra, Advocate, Supreme Court and Delhi High Court.

If the labels succeed in court, Mishra adds potential remedies could include ordering OpenAI to remove copied content within a set timeframe, imposing an injunction to stop its use, awarding damages (possibly in crores) for commercial exploitation, or allowing usage under licensing and royalty terms.

“I draw the line when a song is used to train an algorithm. Legally, music has never been free—when I draw inspiration from music, it’s from something I’ve paid for, whether through cassettes, CDs, or streaming. So why should it be any different for AI? If an algorithm is learning from copyrighted work, it should be properly licensed and compensated,” says Shourya Malhotra, an Indie-folk Singer-Songwriter and a Media & Entertainment Lawyer.

The Indian case–alongside similar suits elsewhere– is seen as a bellwether. Industry groups worldwide are watching the developments closely, since a court ruling that such AI training infringes copyright could force AI firms to change practices or license data.

However, it’s interesting to note that Indian music labels and publishers appear particularly wary of OpenAI alone, despite numerous similar cases emerging globally.

Over the last two years, global copyright lawsuits against AI companies have multiplied, involving authors like Sarah Silverman and Ta-Nehisi Coates, visual artists, and media outlets such as The New York Times, to music industry labels such as Universal Music Group. Collectively, they argue that AI firms have improperly used their content to train highly profitable AI models without permission or compensation.

Last month, more than 400 prominent Hollywood figures signed an open letter urging the U.S. Office of Science and Technology Policy to resist weakening copyright protections at the request of AI companies.

The letter was specifically written in response to recent arguments by OpenAI and Google, both of which claimed that current copyright laws either already permit—or should be updated to permit—AI firms to train their systems on copyrighted materials without permission or compensation to creators.

Legal experts believe that Indian music labels often already have licensing deals or revenue-sharing agreements with Google (especially through YouTube), signalling an already existing established relationship, which may have kept away the firm in the limelight with such lawsuits.

“Google’s stance seems to be more qualified, as compared to OpenAI. The company earlier rolled out a ‘Generative AI Indemnification program’ launched through Google Cloud, covering customers who use Vertex AI and Duet AI models,” Dey says.

It shields them from legal risks if AI-generated content leads to copyright disputes — offering businesses legal protection while encouraging broader AI integration across industries.

Ricky Kej, Shobu Yarlagadda, and Biren Ghose on AI and tech integration in music and film industries

What does the industry think?

Music industry professionals have broadly welcomed the lawsuit, viewing it as a necessary pushback against unlicensed AI use of creative catalogs.

The Indian labels’ action comes on the heels of similar moves globally. For example, in late 2024 Germany’s GEMA (which represents songwriters and publishers) sued OpenAI for ChatGPT’s alleged reproduction of song lyrics used in training.

In 2023, Universal Music Group (UMG), which represents artists Drake and The Weeknd demanded the removal of a song titled “Heart on My Sleeve” from all platforms. The song had gone viral after being published by an anonymous producer who went by the name of “Ghostwriter.” The track used AI to mimic the voices and style of the two artists and had racked up over 600,000 Spotify streams and 15 million TikTok views within days.

Several streaming services including Apple Music, Spotify, SoundCloud, YouTube and others pulled down the AI-generated track citing copyright violations.

In recent months, artists such as Billie Eilish, Pearl Jam, and Celine Dion have voiced concerns about generative AI in music, highlighting issues around creativity and artists’ rights.

These efforts signal another growing industry concern: that AI companies should not be allowed to ingest copyrighted material without approval or compensation.

“Some measures include mandatory disclosure by developers or corporations of the use of copyrighted material along with disclosures about original creators – To credit the creator (and incentivise them, similar to the recommendations that pop up on Spotify and Netflix),” Dey says.

Additionally, he suggests implementing AI-specific licensing models for training data or revenue-sharing frameworks to ensure that artists and rights holders are fairly compensated when their work is used to develop AI models.

“What AI still lacks is the human essence—emotion, personal narratives, and improvisation—which are at the heart of music. The industry must strike a balance between embracing AI’s possibilities and safeguarding the originality and rights of artists,” says Jaspreet Bindra, CEO of AI &Beyond.

Risks on licensing

The traditional licensing framework wasn’t designed for AI training. At present, there is no established system to license music for AI model training or to remunerate artists for AI-generated usage of their work.

“Only two aspects for the time being may be addressed. One, lenient licensing process and fee, and two, AI technology proposed for public interest may be separated from the commercial interest; and accordingly may be regulated,” Advocate Mishra says.

Copyright laws haven’t caught up with AI yet, leaving a grey area on who owns an AI-generated song—whether it's the trainer, the company, or the original artists whose work was used, says Shanit Ghose, Founder of Sur, AI-powered stem splitter and sample library.

“If an AI generates a song, there’s no clear ownership—We need updated legal frameworks that protect original artists while also allowing for ethical AI development. Otherwise, artists could see their styles being used commercially without any credit or compensation,” he says.

![How to Find Low-Competition Keywords with Semrush [Super Easy]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/73/62/7362f16fb9e460b6d58ccc09b4a048b6/how-to-find-low-competition-keywords-sm.png)