Generative AI is learning to spy for the US military

For much of last year, about 2,500 US service members from the 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit sailed aboard three ships throughout the Pacific, conducting training exercises in the waters off South Korea, the Philippines, India, and Indonesia. At the same time, onboard the ships, an experiment was unfolding: The Marines in the unit responsible for…

For much of last year, about 2,500 US service members from the 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit sailed aboard three ships throughout the Pacific, conducting training exercises in the waters off South Korea, the Philippines, India, and Indonesia. At the same time, onboard the ships, an experiment was unfolding: The Marines in the unit responsible for sorting through foreign intelligence and making their superiors aware of possible local threats were for the first time using generative AI to do it, testing a leading AI tool the Pentagon has been funding.

Two officers tell us that they used the new system to help scour thousands of pieces of open-source intelligence—nonclassified articles, reports, images, videos—collected in the various countries where they operated, and that it did so far faster than was possible with the old method of analyzing them manually. Captain Kristin Enzenauer, for instance, says she used large language models to translate and summarize foreign news sources, while Captain Will Lowdon used AI to help write the daily and weekly intelligence reports he provided to his commanders.

“We still need to validate the sources,” says Lowdon. But the unit’s commanders encouraged the use of large language models, he says, “because they provide a lot more efficiency during a dynamic situation.”

The generative AI tools they used were built by the defense-tech company Vannevar Labs, which in November was granted a production contract worth up to $99 million by the Pentagon’s startup-oriented Defense Innovation Unit with the goal of bringing its intelligence tech to more military units. The company, founded in 2019 by veterans of the CIA and US intelligence community, joins the likes of Palantir, Anduril, and Scale AI as a major beneficiary of the US military’s embrace of artificial intelligence—not only for physical technologies like drones and autonomous vehicles but also for software that is revolutionizing how the Pentagon collects, manages, and interprets data for warfare and surveillance.

Though the US military has been developing computer vision models and similar AI tools, like those used in Project Maven, since 2017, the use of generative AI—tools that can engage in human-like conversation like those built by Vannevar Labs—represent a newer frontier.

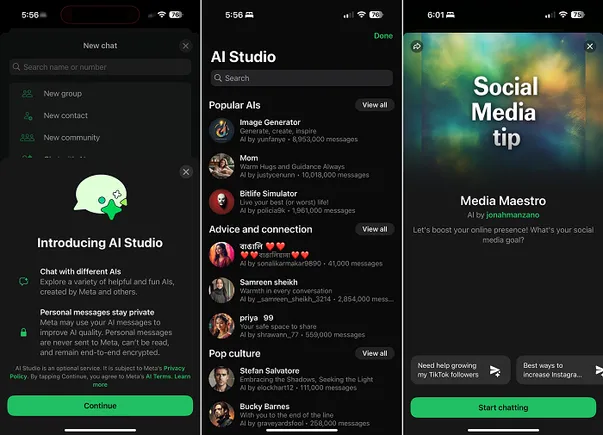

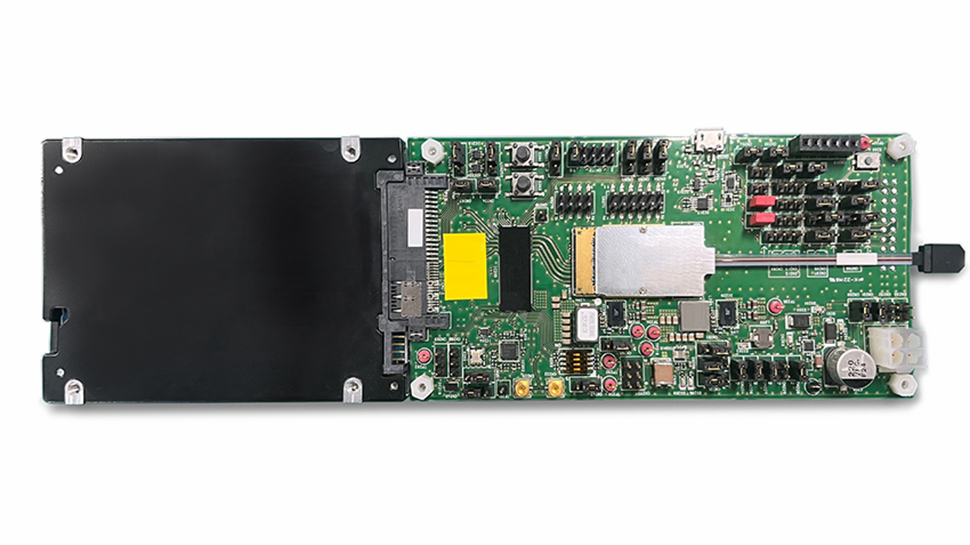

The company applies existing large language models, including some from OpenAI and Microsoft, and some bespoke ones of its own to troves of open-source intelligence the company has been collecting since 2021. The scale at which this data is collected is hard to comprehend (and a large part of what sets Vannevar’s products apart): terabytes of data in 80 different languages are hoovered every day in 180 countries. The company says it is able to analyze social media profiles and breach firewalls in countries like China to get hard-to-access information; it also uses nonclassified data that is difficult to get online (gathered by human operatives on the ground), as well as reports from physical sensors that covertly monitor radio waves to detect illegal shipping activities.

Vannevar then builds AI models to translate information, detect threats, and analyze political sentiment, with the results delivered through a chatbot interface that’s not unlike ChatGPT. The aim is to provide customers with critical information on topics as varied as international fentanyl supply chains and China’s efforts to secure rare earth minerals in the Philippines.

“Our real focus as a company,” says Scott Philips, Vannevar Labs’ chief technology officer, is to “collect data, make sense of that data, and help the US make good decisions.”

That approach is particularly appealing to the US intelligence apparatus because for years the world has been awash in more data than human analysts can possibly interpret—a problem that contributed to the 2003 founding of Palantir, a company now worth nearly $217 billion and known for its powerful and controversial tools, including a database that helps Immigration and Customs Enforcement search for and track information on undocumented immigrants.

In 2019, Vannevar saw an opportunity to use large language models, which were then new on the scene, as a novel solution to the data conundrum. The technology could enable AI not just to collect data but to actually talk through an analysis with someone interactively.

Vannevar’s tools proved useful for the deployment in the Pacific, and Enzenauer and Lowdon say that while they were instructed to always double-check the AI’s work, they didn’t find inaccuracies to be a significant issue. Enzenauer regularly used the tool to track any foreign news reports in which the unit’s exercises were mentioned and to perform sentiment analysis, detecting the emotions and opinions expressed in text. Judging whether a foreign news article reflects a threatening or friendly opinion toward the unit is a task that on previous deployments she had to do manually.

“It was mostly by hand—researching, translating, coding, and analyzing the data,” she says. “It was definitely way more time-consuming than it was when using the AI.”

Still, Enzenauer and Lowdon say there were hiccups, some of which would affect most digital tools: The ships had spotty internet connections much of the time, limiting how quickly the AI model could synthesize foreign intelligence, especially if it involved photos or video.

With this first test completed, the unit’s commanding officer, Colonel Sean Dynan, said on a call with reporters in February that heavier use of generative AI was coming; this experiment was “the tip of the iceberg.”

This is indeed the direction that the entire US military is barreling toward at full speed. In December, the Pentagon said it will spend $100 million in the next two years on pilots specifically for generative AI applications. In addition to Vannevar, it’s also turning to Microsoft and Palantir, which are working together on AI models that would make use of classified data. (The US is of course not alone in this approach; notably, Israel has been using AI to sort through information and even generate lists of targets in its war in Gaza, a practice that has been widely criticized.)

Perhaps unsurprisingly, plenty of people outside the Pentagon are warning about the potential risks of this plan, including Heidy Khlaaf, who is chief AI scientist at the AI Now Institute, a research organization, and has expertise in leading safety audits for AI-powered systems. She says this rush to incorporate generative AI into military decision-making ignores more foundational flaws of the technology: “We’re already aware of how LLMs are highly inaccurate, especially in the context of safety-critical applications that require precision.”

One particular use case that concerns her is sentiment analysis, which she argues is “a highly subjective metric that even humans would struggle to appropriately assess based on media alone.”

If AI perceives hostility toward US forces where a human analyst would not—or if the system misses hostility that is really there—the military could make an misinformed decision or escalate a situation unnecessarily.

Sentiment analysis is indeed a task that AI has not perfected. Philips, the Vannevar CTO, says the company has built models specifically to judge whether an article is pro-US or not, but MIT Technology Review was not able to evaluate them.

Chris Mouton, a senior engineer for RAND, recently tested how well-suited generative AI is for the task. He evaluated leading models, including OpenAI’s GPT-4 and an older version of GPT fine-tuned to do such intelligence work, on how accurately they flagged foreign content as propaganda compared with human experts. “It’s hard,” he says, noting that AI struggled to identify more subtle types of propaganda. But he adds that the models could still be useful in lots of other analysis tasks.

Another limitation of Vannevar’s approach, Khlaaf says, is that the usefulness of open-source intelligence is debatable. Mouton says that open-source data can be “pretty extraordinary,” but Khlaaf points out that unlike classified intel gathered through reconnaissance or wiretaps, it is exposed to the open internet—making it far more susceptible to misinformation campaigns, bot networks, and deliberate manipulation, as the US Army has warned.

For Mouton, the biggest open question now is whether these generative AI technologies will be simply one investigatory tool among many that analysts use—or whether they’ll produce the subjective analysis that’s relied upon and trusted in decision-making. “This is the central debate,” he says.

What everyone agrees is that AI models are accessible—you can just ask them a question about complex pieces of intelligence, and they’ll respond in plain language. But it’s still in dispute what imperfections will be acceptable in the name of efficiency.

![How to Find Low-Competition Keywords with Semrush [Super Easy]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/73/62/7362f16fb9e460b6d58ccc09b4a048b6/how-to-find-low-competition-keywords-sm.png)