Tokyo is reinventing the downtown—by making more than one

The death of downtown is now a familiar refrain. Central business districts (CBDs) in cities around the world—once bustling centers of office work—were hit hard by the pandemic and the shift to remote work, leading many to predict they would never fully recover. But instead of demise, downtowns are being reinvented. And Tokyo is leading the way. Traditional downtown business districts in cities around the world were defined and dominated by vertical towers where legions of white-collar professionals and support staff were stacked in isolated office buildings. The world’s largest metropolitan area is pioneering a new model where the city itself increasingly takes on functions that were once the province of the office, providing amenities and specialized services that enable companies to better attract and retain talent. Instead of a single monolithic CBD, Tokyo’s downtown has been reshaped into a mosaic of distinct downtown districts with their own that together make up its vibrant urban core. Each of them has its own distinct economic identity and unique mix of amenities which allow them to appeal to different kinds of talent. Evolving gradually over the past two decades, this approach is both an organic outgrowth of private sector shifts on development and office location, as well as innovative policies that relax zoning, incentivize mixed-use development, and prioritize public transport access. It also helps that people in Tokyo live in smaller homes and enjoy quick, reliable commutes on clean, efficient trains and subways—conditions that naturally support the return to office work. Taken together, these factors have enabled Tokyo’s downtown to experience one of the world’s strongest rebounds, with high rates of office return, higher commercial rents, and lower vacancy rates than nearly any other global city. [Image: courtesy of the authors] We call this new model an urban knowledge campus. Indeed, Tokyo’s downtown districts resemble university campuses more than traditional downtown office clusters. After all, a great university campus is more than just a collection of lecture halls, dormitories, and dining facilities. It forms a complete ecosystem for learning, social interaction, and spontaneous exchange, encompassing labs and studios, sports and athletic centers, theaters, cultural venues, and green spaces. Our detailed research, released by the BCG Henderson Institute, examined five of Tokyo’s most prominent downtown districts—Marunouchi and Nihonbashi, Shibuya, Roppongi, Shinagawa, and Shinjuku—and identified the key characteristics that underpin their collective success as an urban knowledge campus. Density Done Right Tokyo’s downtown districts are among the densest, most intensively used urban spaces on the planet. With daytime populations exceeding 70,000 people per square kilometer in some areas, they are twice as dense as Manhattan but remain clean, orderly, and deeply livable. It’s this level of functional density that distinguishes Tokyo from more suburban innovation hubs like Silicon Valley or Boston’s Route 128. A True Urban Mix Tokyo is distinguished by more than physical density. Its messy, mixed-use urbanity fosters what we call interaction density—the constant, unplanned collisions that spark new ideas and connections. Office spaces intermingle with housing, vibrant retail, green spaces, restaurants, bars, clubs, cultural venues—and, importantly, schools and childcare facilities which help keep families with children in and around the urban core. In fact, office space accounts for less than 40% of land use in four of Tokyo’s five major downtown districts—far lower than in London’s Canary Wharf, where it exceeds 80%; Paris’s La Défense, where it makes up roughly 70%; or Lower Manhattan, where it comprises some 60%. [Image: courtesy of the authors] Tokyo’s downtowns districts are 24/7 neighborhoods bustling with life long after business hours—a striking contrast to the CBDs of many global cities that are dominated by monolithic office towers and empty out after dark. A Mosaic of Distinctive Districts Tokyo’s urban knowledge campus isn’t a single entity but rather a mosaic of specialized urban environments that appeal to distinct industries. The unique amenities, services, and character, these districts appeal to different kinds of talent these industries require. This specialization is reflected in the chart below which arrays the city’s five main downtown districts based on two key factors: how specialized each is around particular industries, and how much of each district is dedicated to office space versus other uses. [Image: courtesy of the authors] Marunouchi-Nihonbashi is comprised of two adjacent districts in central Tokyo that serve as the hub for the city’s financial and professional services industries. These districts attract finance professionals, strategic consultants, senior executives, and corporate leaders. They have th

The death of downtown is now a familiar refrain. Central business districts (CBDs) in cities around the world—once bustling centers of office work—were hit hard by the pandemic and the shift to remote work, leading many to predict they would never fully recover.

But instead of demise, downtowns are being reinvented. And Tokyo is leading the way.

Traditional downtown business districts in cities around the world were defined and dominated by vertical towers where legions of white-collar professionals and support staff were stacked in isolated office buildings. The world’s largest metropolitan area is pioneering a new model where the city itself increasingly takes on functions that were once the province of the office, providing amenities and specialized services that enable companies to better attract and retain talent.

Instead of a single monolithic CBD, Tokyo’s downtown has been reshaped into a mosaic of distinct downtown districts with their own that together make up its vibrant urban core. Each of them has its own distinct economic identity and unique mix of amenities which allow them to appeal to different kinds of talent.

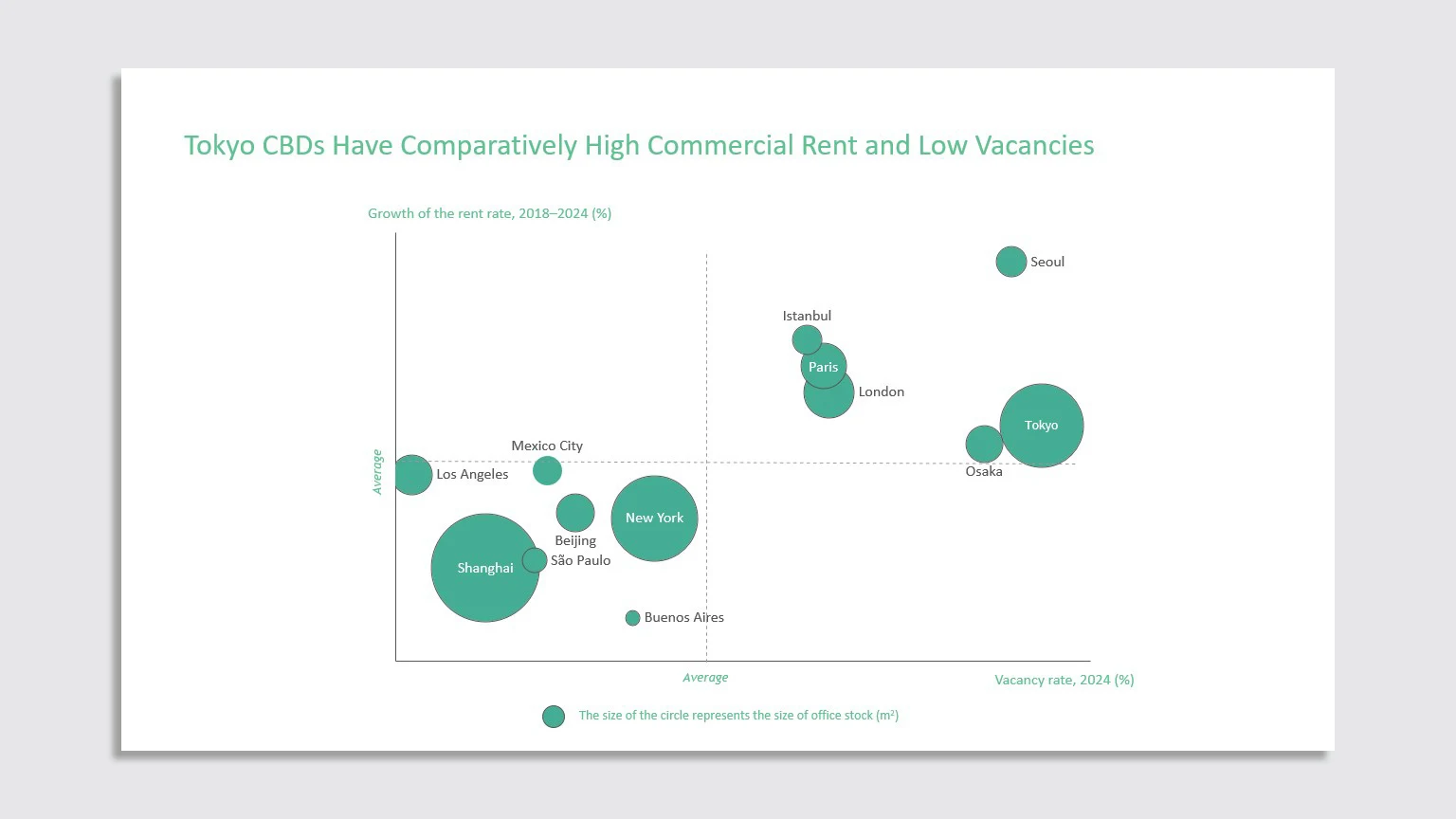

Evolving gradually over the past two decades, this approach is both an organic outgrowth of private sector shifts on development and office location, as well as innovative policies that relax zoning, incentivize mixed-use development, and prioritize public transport access. It also helps that people in Tokyo live in smaller homes and enjoy quick, reliable commutes on clean, efficient trains and subways—conditions that naturally support the return to office work. Taken together, these factors have enabled Tokyo’s downtown to experience one of the world’s strongest rebounds, with high rates of office return, higher commercial rents, and lower vacancy rates than nearly any other global city.

We call this new model an urban knowledge campus. Indeed, Tokyo’s downtown districts resemble university campuses more than traditional downtown office clusters. After all, a great university campus is more than just a collection of lecture halls, dormitories, and dining facilities. It forms a complete ecosystem for learning, social interaction, and spontaneous exchange, encompassing labs and studios, sports and athletic centers, theaters, cultural venues, and green spaces.

Our detailed research, released by the BCG Henderson Institute, examined five of Tokyo’s most prominent downtown districts—Marunouchi and Nihonbashi, Shibuya, Roppongi, Shinagawa, and Shinjuku—and identified the key characteristics that underpin their collective success as an urban knowledge campus.

Density Done Right

Tokyo’s downtown districts are among the densest, most intensively used urban spaces on the planet. With daytime populations exceeding 70,000 people per square kilometer in some areas, they are twice as dense as Manhattan but remain clean, orderly, and deeply livable. It’s this level of functional density that distinguishes Tokyo from more suburban innovation hubs like Silicon Valley or Boston’s Route 128.

A True Urban Mix

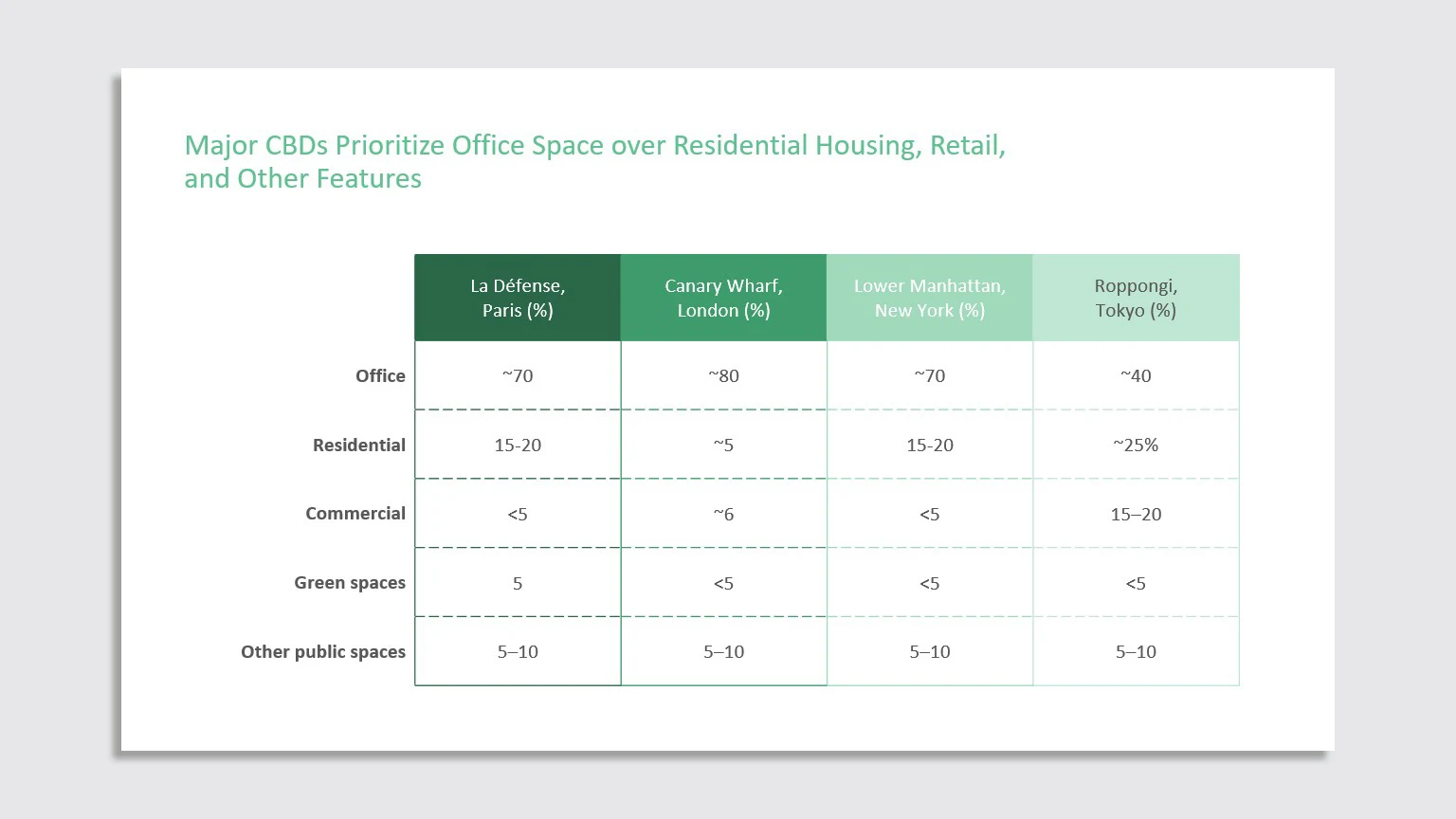

Tokyo is distinguished by more than physical density. Its messy, mixed-use urbanity fosters what we call interaction density—the constant, unplanned collisions that spark new ideas and connections. Office spaces intermingle with housing, vibrant retail, green spaces, restaurants, bars, clubs, cultural venues—and, importantly, schools and childcare facilities which help keep families with children in and around the urban core.

In fact, office space accounts for less than 40% of land use in four of Tokyo’s five major downtown districts—far lower than in London’s Canary Wharf, where it exceeds 80%; Paris’s La Défense, where it makes up roughly 70%; or Lower Manhattan, where it comprises some 60%.

Tokyo’s downtowns districts are 24/7 neighborhoods bustling with life long after business hours—a striking contrast to the CBDs of many global cities that are dominated by monolithic office towers and empty out after dark.

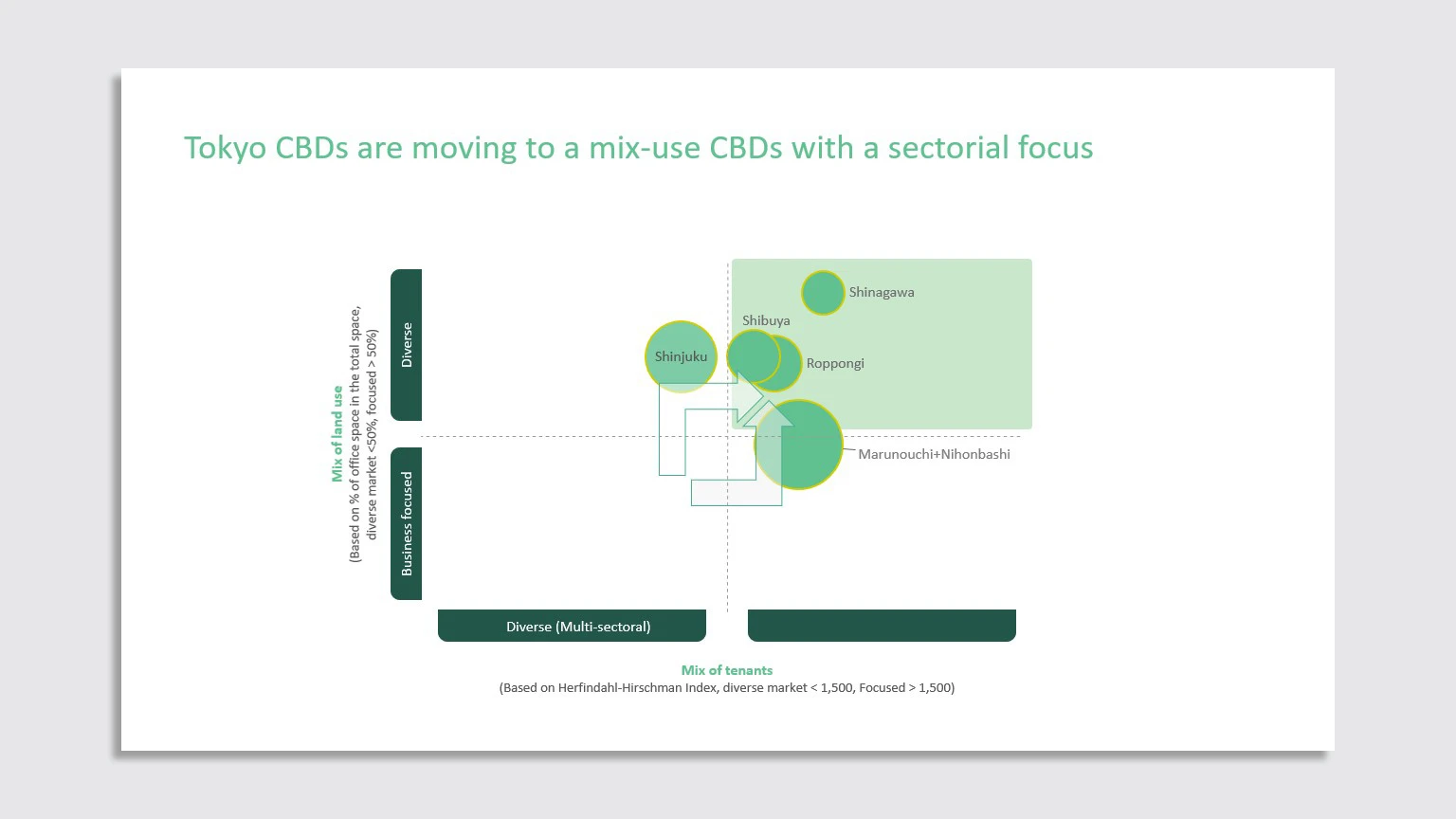

A Mosaic of Distinctive Districts

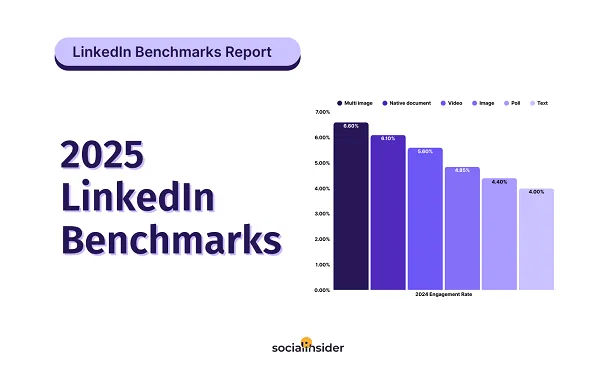

Tokyo’s urban knowledge campus isn’t a single entity but rather a mosaic of specialized urban environments that appeal to distinct industries. The unique amenities, services, and character, these districts appeal to different kinds of talent these industries require. This specialization is reflected in the chart below which arrays the city’s five main downtown districts based on two key factors: how specialized each is around particular industries, and how much of each district is dedicated to office space versus other uses.

Marunouchi-Nihonbashi is comprised of two adjacent districts in central Tokyo that serve as the hub for the city’s financial and professional services industries. These districts attract finance professionals, strategic consultants, senior executives, and corporate leaders. They have the highest level of industry specialization, and offices make up the largest share of their total footprint. Anchored by major banks, global headquarters, and consultancies, these districts exude stability and formality, with prestige modern skyscrapers rising beside historic facades, and streets lined with luxury retail, fine dining, and shaded plazas.

Roppongi has evolved into a cosmopolitan center for technology and international business. It has a moderate level of industry specialization compared to Marunouchi-Nihonbashi and a greater variety of non-office uses. Drawing on its historic role as a hub for expatriates, it has become Tokyo’s main center for global corporations and international talent. Once known primarily for nightlife and dining, it now offers a more balanced set of amenities, including more sophisticated arts and culture venues, abundant green spaces, and schools and educational facilities for families.

Shibuya is the city’s creative and digital epicenter, home to media firms, startups, and tech ventures. Its specialization and mix of uses are similar to Roppongi. The district is a magnet for the creative class: designers, coders, digital media workers, and creative professionals who thrive on collaboration, improvisation, and inspiration. Its colorful, neon-lit streetscape pulses with energy, featuring avant-garde architecture, ramen shops, clubs, pop-up boutiques, and live-music venues. Loud, fast, and experimental, Shibuya’s edgy vibe was a key factor in Google’s decision to place its Japanese headquarters here.

Shinjuku stands out as more balanced in terms of its industry mix and use of space. It attracts a diverse workforce—bureaucrats, executives, business travelers, and creatives—to its mix of government offices, high-rise hotels, entertainment venues, shops, and transit terminals. With amenities ranging from policy think tanks to karaoke bars, it’s the most “Tokyo” of the city’s districts: dense, vertical, chaotic, and dynamic.

Lessons for Corporate Location Strategy

Companies in the U.S. and around the world have much to learn from what Tokyo has done. Choosing a location isn’t merely about real estate or cost; it’s about strategically positioning organizations in areas that can help attract, energize, and retain essential talent.

The office today is more than a building or a place to work; it’s a platform for culture, community, and innovation. The urban knowledge campus is what this looks like when scaled to the level of the city.

At a time when talented people have more choice than ever, companies must move beyond the idea that workers should simply report to an office. They must place themselves in locations that excite and inspire. The knowledge campus functions more as a magnet than a mandate.

Companies must elevate location as a core element of their overall corporate strategy. Where a company chooses to locate shapes its culture, its innovation capacity, and its prospects for growth. Forward-thinking firms increasingly understand that talent attraction depends on far more than amenities inside the office. It depends on the quality of the broader environment—transit access, housing, schools, safety, vibrancy, and a sense of place.

But this goes beyond simply selecting great locations. To truly succeed in this new era, companies must engage proactively in shaping the environments they inhabit, partnering with developers, local governments, and other institutions to co-create the kinds of neighborhoods that support their workforce and long-term success.

In Tokyo, private developers have played a critical role in evolving the downtown districts into more livable, vibrant spaces. And such development has been facilitated by government policies that allow greater land-use flexibility; encourage mixed-use development; provide transit connectivity; and fill the urban core with schools, child-care facilities, and other essential services that keep families with children in the urban center alongside young people and empty-nesters. Such long-term public investments in urban ecosystems enable companies to thrive. Tokyo’s experience shows what’s possible when companies, developers, and government are aligned around making great places for companies and for people.

In today’s knowledge economy, place matters more than ever. Choosing a location isn’t just about selecting an address—it’s the cornerstone of sustained competitive advantage.

This research was conducted under the auspices of the BCG Henderson Institute.

![How to Find Low-Competition Keywords with Semrush [Super Easy]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/73/62/7362f16fb9e460b6d58ccc09b4a048b6/how-to-find-low-competition-keywords-sm.png)