Pizza and groceries now—pay later: Klarna and Affirm’s big branding moment

Branded is a weekly column devoted to the intersection of marketing, business, design, and culture. With economic uncertainty, inflation, and high interest rates lingering, consumers who can’t decide whether to spend now or hold off until later are increasingly doing some of each. And that’s good news for the “buy now, pay later” business. Buy now, pay later (BNPL) options—including those facilitated by major BNPL services like Klarna, Afterpay, and Affirm—have been growing increasingly commonplace. According to an April survey from LendingTree, for example, 25% of BNPL users have spent the loans on groceries, up from 14% last year. And the services are becoming more widely known through linkups with familiar brands. Klarna—which filed IPO paperwork in March but reportedly put those plans on hold when the markets swooned last month—recently announced a partnership with DoorDash to enable customers to pay for deliveries in installments. And Affirm has a new deal with Costco that will give approved customers monthly payment options. Interest in BNPL is likely to grow as tariffs cause prices to rise (Walmart, for instance, just warned of price hikes). This builds on a steady rise of BNPL spending that goes back several years. This past holiday season, such spending hit an all-time high of $18.2 billion, up nearly 10% over the prior year, according to data from Adobe, which listed popular categories such as electronics, apparel, and video games. Research from EMarketer found that the “per user spend” on BNPL services topped $1,000 in 2024, and forecast the category will make up 1.4% of all retail sales this year. BNPL firms position their steady move into everyday spending categories as a matter of convenience and household budgeting flexibility. The loans are generally interest-free to consumers, with the services charging merchants a small percentage (ranging from an estimated 1.5% to 7%) of the total transaction. The merchant benefits from increased sales from consumers who presumably feel more open to spending if they can spread out the impact, and avoid adding to credit card debt. Of course there’s a flip side to that. Critics argue that the services exploit consumer psychology, underscoring the instant gratification of buying something new at just a fraction of the total price now—a temptation that overwhelms the reality of continuing to pay it off for months. While BNPL offerings are fundamentally similar to old-school layaway plans and the like, they’re much easier to qualify for, and often pop up as seamless options on e-commerce sites. Moreover, the services make money from late fees if an overextended consumer falls behind. Roughly 41% of BNPL users copped to paying late in the past year, compared to 34% a year ago. Most were only a week or so late, and many of the laggards were in higher-income categories, but that’s a notable trend at a time when total consumer debt stands at a record $18.2 trillion. Either way, the expanding popularity of BNPL options for quotidian purposes like takeout and groceries is seen by many as a bad economic indicator: Surely an increased interest in alternative payment schemes to fund pizza night sounds like a sign of a skittish consumer. And while the use of BNPL options has been growing for some time, it has done so at a somewhat slower pace in the relatively positive economy of the past few years; by comparison, adoption spiked during and in the aftermath of the pandemic downturn. And there’s no question that services like Affirm and Klarna are becoming an increasingly routine part of the consumer-spending landscape. Recent fears of tariff-fueled inflation, shortages in some retail and grocery categories, and perhaps even a recession actually make the idea of buying now—before things get even worse—sound particularly appealing, and rational. Ultimately, both assessments of BNPL can be true at the same time: It’s a convenient and potentially sensible option, and a worrisome trend. Discussing his firm’s latest data, Matt Schulz, LendingTree’s chief consumer finance analyst, told CNBC that the popularity of BNPL reflects economic headwinds and uncertainty that has lots of consumers “struggling” and looking for ways to extend their budgets. “For an awful lot of people, that’s going to mean leaning on buy now, pay later loans,” he said, “for better or for worse.”

Branded is a weekly column devoted to the intersection of marketing, business, design, and culture.

With economic uncertainty, inflation, and high interest rates lingering, consumers who can’t decide whether to spend now or hold off until later are increasingly doing some of each. And that’s good news for the “buy now, pay later” business.

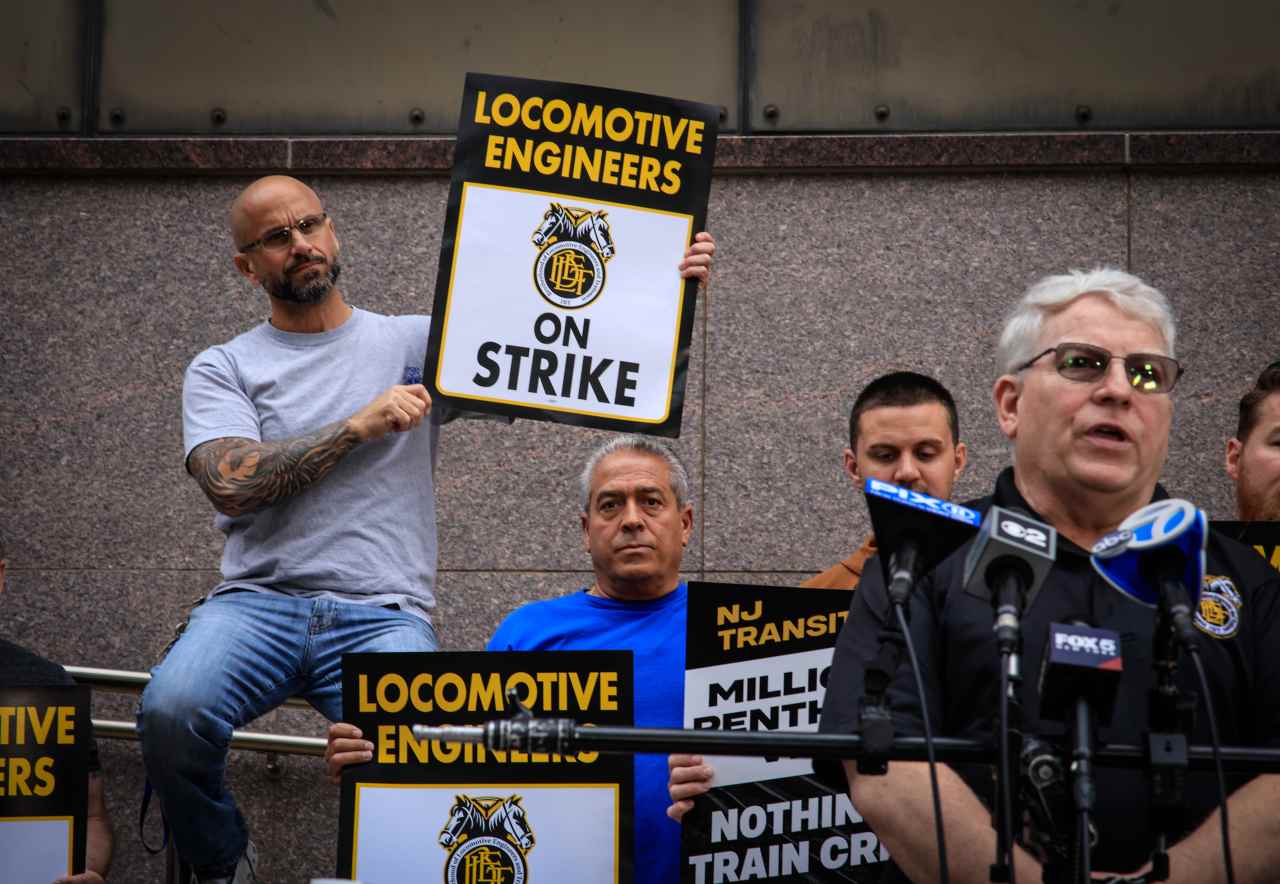

Buy now, pay later (BNPL) options—including those facilitated by major BNPL services like Klarna, Afterpay, and Affirm—have been growing increasingly commonplace. According to an April survey from LendingTree, for example, 25% of BNPL users have spent the loans on groceries, up from 14% last year.

And the services are becoming more widely known through linkups with familiar brands. Klarna—which filed IPO paperwork in March but reportedly put those plans on hold when the markets swooned last month—recently announced a partnership with DoorDash to enable customers to pay for deliveries in installments. And Affirm has a new deal with Costco that will give approved customers monthly payment options. Interest in BNPL is likely to grow as tariffs cause prices to rise (Walmart, for instance, just warned of price hikes).

This builds on a steady rise of BNPL spending that goes back several years. This past holiday season, such spending hit an all-time high of $18.2 billion, up nearly 10% over the prior year, according to data from Adobe, which listed popular categories such as electronics, apparel, and video games. Research from EMarketer found that the “per user spend” on BNPL services topped $1,000 in 2024, and forecast the category will make up 1.4% of all retail sales this year.

BNPL firms position their steady move into everyday spending categories as a matter of convenience and household budgeting flexibility. The loans are generally interest-free to consumers, with the services charging merchants a small percentage (ranging from an estimated 1.5% to 7%) of the total transaction. The merchant benefits from increased sales from consumers who presumably feel more open to spending if they can spread out the impact, and avoid adding to credit card debt.

Of course there’s a flip side to that. Critics argue that the services exploit consumer psychology, underscoring the instant gratification of buying something new at just a fraction of the total price now—a temptation that overwhelms the reality of continuing to pay it off for months. While BNPL offerings are fundamentally similar to old-school layaway plans and the like, they’re much easier to qualify for, and often pop up as seamless options on e-commerce sites.

Moreover, the services make money from late fees if an overextended consumer falls behind. Roughly 41% of BNPL users copped to paying late in the past year, compared to 34% a year ago. Most were only a week or so late, and many of the laggards were in higher-income categories, but that’s a notable trend at a time when total consumer debt stands at a record $18.2 trillion.

Either way, the expanding popularity of BNPL options for quotidian purposes like takeout and groceries is seen by many as a bad economic indicator: Surely an increased interest in alternative payment schemes to fund pizza night sounds like a sign of a skittish consumer. And while the use of BNPL options has been growing for some time, it has done so at a somewhat slower pace in the relatively positive economy of the past few years; by comparison, adoption spiked during and in the aftermath of the pandemic downturn.

And there’s no question that services like Affirm and Klarna are becoming an increasingly routine part of the consumer-spending landscape. Recent fears of tariff-fueled inflation, shortages in some retail and grocery categories, and perhaps even a recession actually make the idea of buying now—before things get even worse—sound particularly appealing, and rational.

Ultimately, both assessments of BNPL can be true at the same time: It’s a convenient and potentially sensible option, and a worrisome trend. Discussing his firm’s latest data, Matt Schulz, LendingTree’s chief consumer finance analyst, told CNBC that the popularity of BNPL reflects economic headwinds and uncertainty that has lots of consumers “struggling” and looking for ways to extend their budgets. “For an awful lot of people, that’s going to mean leaning on buy now, pay later loans,” he said, “for better or for worse.”

![[Weekly funding roundup May 10-16] Large deals remain a no-show](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/220356402d6d11e9aa979329348d4c3e/Weekly-funding-1741961216560.jpg)

![Epic Games: Fortnite is offline for Apple devices worldwide after app store rejection [updated]](https://helios-i.mashable.com/imagery/articles/00T6DmFkLaAeJiMZlCJ7eUs/hero-image.fill.size_1200x675.v1747407583.jpg)

.jpg)