This iconic NASA office changed climate science forever. DOGE plans to kill it

In recent months, the drama around Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), President Trump’s efforts to defund federal agencies, and the court cases challenging these moves have consumed the news. It’s understandable that an announcement last month about a small office lease on the Upper West Side of Manhattan being canceled didn’t get much attention. But that 43,000-square-foot space near Columbia University is home to the Goddard Institute for Space Studies, or GISS, a NASA research outfit, think tank, and pioneer in climate change research that will see its lease terminated by the end of the month, per a NASA spokesperson. Currently, the institute has no permanent home to move into. It’s likely you’ve seen the building, even if you’re not aware of the monumental achievements that have taken place there. The exterior shot of the diner in Seinfeld features that exact building; for decades, scientists working inside have dealt with an occasional fan taking selfies outside. [Photo: Roberto Machado Noa/LightRocket/Getty Images] You’re also probably more aware of the ideas hatched inside than you think. During the ’60s, when the institute was founded, the terms black hole and quasar were coined inside its walls. In the late ’80s, NASA scientist James Hansen became famous for his warnings about the dangers posed by climate change. He was then the head of GISS, and the climate modeling that he and his colleagues did there proved the case. “This is the place we came finally to understand the threat to the Earth that global warming represented—the biggest threat in the history of our species,” climate advocate and author Bill McKibben told Fast Company. “Nothing less than that. Their datasets were what allowed Hansen to go before Congress and speak with authority. He had the numbers and no one else did.” The end of GISS as we know it represents many things, including the damage the Trump administration’s cost-cutting is doing to American scientific preeminence. Current head Gavin Schmidt said without funds for a new lease, he’s racing to find a new home. (Though staffers haven’t been told where they’re moving to, as of yet, none have been terminated; a NASA spokesperson said, “Over the next several months, employees will be placed on temporary remote work agreements while NASA seeks and evaluates options for a new space for the GISS team.”) The move comes as the federal government has decried climate science, cut jobs at NASA, and proposed curtailing its mission. But even the existence of GISS showcases the power of a small group of curious, driven people who, if given resources and freedom, can accomplish incredible things. “There is something that is quite distinct to working for NASA,” said Schmidt. “Because, literally the whole universe is your subject.” A postcard for the Oxford Hotel, circa 1930-1945 [Image: Digital Commonwealth] A Small Office With Expansive Freedoms Located across a few floors in a former apartment building, GISS has never been a well-outfitted office. “Until recently, it was a shithole,” said Schmidt, who noted that even though a long-overdue renovation was just finished, the air-conditioning system is still pretty much nonfunctional. But the office decor was never the attraction. It was the people you could bump into. Named after rocketry pioneer Robert Goddard, the institute was established in 1961, and initially called the Institute for Space Studies. It was led by Robert Jastrow, a celebrated researcher and public figure who would help millions of Americans learn about space via prolific writings and TV appearances. Locating in New York City helped attract the leading lights of academia from surrounding universities. Jastrow said the institute’s goal was to “arouse the interest and enlist the participation of this rich scientific community.” It became a hotbed for debate and ideas, hosting seminars and talks that are credited with birthing the concepts behind black holes, quasars, and plate tectonics. A sidewalk bookseller who specialized in sci-fi books positioned himself nearby to pick up business from the high concentration of astrophysicists. Jastrow could be a competitive and energetic boss—he would push researchers to pull all-nighters and even get them to run laps with him around Central Park—but academic freedom remained paramount. “GISS, from the very beginning, was set up as a place with a light federal presence,” said Schmidt, who took the reins at the institute in 2014. “There would be civil servants, but most of the people there would be postdocs early in their career. The idea was to have this kind of fervent, enthusiastic, free from programmatic responsibilities [space]. It wasn’t an operational center. We had a lot of workshops.” In the ’70s, Hansen and others helped work on projects that sent probes to other planets, including Venus and Jupiter. By the early ’80s, NASA changed its focus to what was c

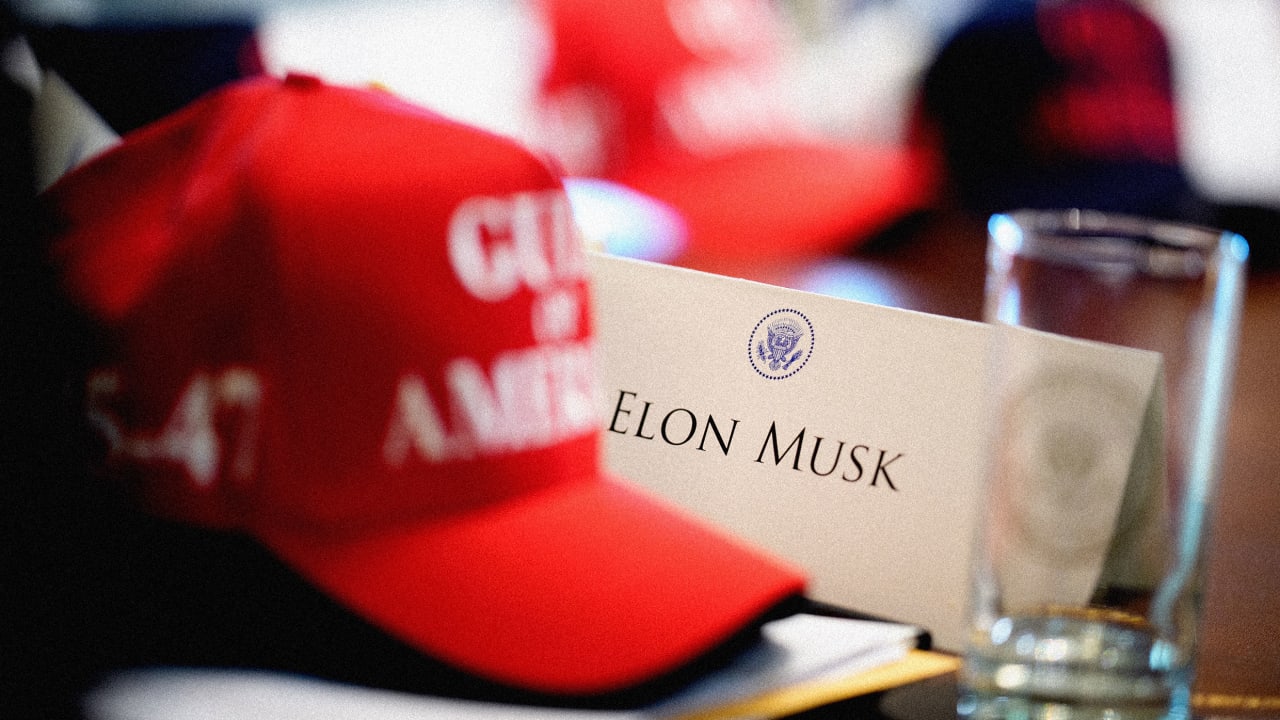

In recent months, the drama around Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), President Trump’s efforts to defund federal agencies, and the court cases challenging these moves have consumed the news. It’s understandable that an announcement last month about a small office lease on the Upper West Side of Manhattan being canceled didn’t get much attention.

But that 43,000-square-foot space near Columbia University is home to the Goddard Institute for Space Studies, or GISS, a NASA research outfit, think tank, and pioneer in climate change research that will see its lease terminated by the end of the month, per a NASA spokesperson. Currently, the institute has no permanent home to move into.

It’s likely you’ve seen the building, even if you’re not aware of the monumental achievements that have taken place there. The exterior shot of the diner in Seinfeld features that exact building; for decades, scientists working inside have dealt with an occasional fan taking selfies outside.

You’re also probably more aware of the ideas hatched inside than you think. During the ’60s, when the institute was founded, the terms black hole and quasar were coined inside its walls. In the late ’80s, NASA scientist James Hansen became famous for his warnings about the dangers posed by climate change. He was then the head of GISS, and the climate modeling that he and his colleagues did there proved the case.

“This is the place we came finally to understand the threat to the Earth that global warming represented—the biggest threat in the history of our species,” climate advocate and author Bill McKibben told Fast Company. “Nothing less than that. Their datasets were what allowed Hansen to go before Congress and speak with authority. He had the numbers and no one else did.”

The end of GISS as we know it represents many things, including the damage the Trump administration’s cost-cutting is doing to American scientific preeminence. Current head Gavin Schmidt said without funds for a new lease, he’s racing to find a new home. (Though staffers haven’t been told where they’re moving to, as of yet, none have been terminated; a NASA spokesperson said, “Over the next several months, employees will be placed on temporary remote work agreements while NASA seeks and evaluates options for a new space for the GISS team.”) The move comes as the federal government has decried climate science, cut jobs at NASA, and proposed curtailing its mission.

But even the existence of GISS showcases the power of a small group of curious, driven people who, if given resources and freedom, can accomplish incredible things.

“There is something that is quite distinct to working for NASA,” said Schmidt. “Because, literally the whole universe is your subject.”

A Small Office With Expansive Freedoms

Located across a few floors in a former apartment building, GISS has never been a well-outfitted office.

“Until recently, it was a shithole,” said Schmidt, who noted that even though a long-overdue renovation was just finished, the air-conditioning system is still pretty much nonfunctional.

But the office decor was never the attraction. It was the people you could bump into. Named after rocketry pioneer Robert Goddard, the institute was established in 1961, and initially called the Institute for Space Studies. It was led by Robert Jastrow, a celebrated researcher and public figure who would help millions of Americans learn about space via prolific writings and TV appearances. Locating in New York City helped attract the leading lights of academia from surrounding universities.

Jastrow said the institute’s goal was to “arouse the interest and enlist the participation of this rich scientific community.” It became a hotbed for debate and ideas, hosting seminars and talks that are credited with birthing the concepts behind black holes, quasars, and plate tectonics. A sidewalk bookseller who specialized in sci-fi books positioned himself nearby to pick up business from the high concentration of astrophysicists. Jastrow could be a competitive and energetic boss—he would push researchers to pull all-nighters and even get them to run laps with him around Central Park—but academic freedom remained paramount.

“GISS, from the very beginning, was set up as a place with a light federal presence,” said Schmidt, who took the reins at the institute in 2014. “There would be civil servants, but most of the people there would be postdocs early in their career. The idea was to have this kind of fervent, enthusiastic, free from programmatic responsibilities [space]. It wasn’t an operational center. We had a lot of workshops.”

In the ’70s, Hansen and others helped work on projects that sent probes to other planets, including Venus and Jupiter. By the early ’80s, NASA changed its focus to what was called mission Earth; the agency realized it knew more about the polar ice caps on Mars than it did the polar ice caps on Earth, and sought to rectify that.

In analyzing Earth’s climate, the previous GISS work on other-planetary atmospheres came in handy. Those frameworks could be applied to Earth’s climate, and its change over time. In addition to that deep bench of multifaceted scientific talent, GISS also had the gear. At the time, it had one of the most powerful computers in operation. While it still used punch cards and spinning disks, it enabled researchers to create the most sophisticated models of climate change that had been done thus far.

McKibben remembers spending time by this machine, as Hansen explained what was being computed.

“I would have been there in the late ’80s, right before or after Hansen’s testimony [before Congress],” he said. “I went a bunch of times, and he showed me around the mainframes and interpreted for me what they were spitting out. It was classic big science of that era—spinning disks and all.”

Why Its Climate Models Remain So Valuable

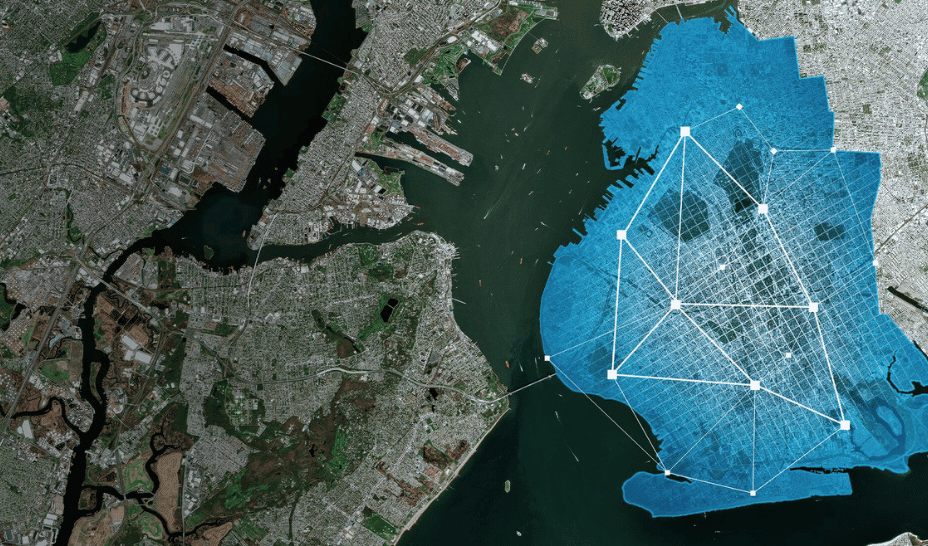

Having that technology, steady support, and a revolving cast of experts made it a perfect place to perfect climate modeling. According to Schmidt, as the task of analyzing the climate became more and more complicated, there basically ceased to be university-based climate modeling to predict future temperature shifts a few decades ago. Everything globally is done at labs like GISS, and it offers a substantial benefit to research around the world. The institute’s famous temperature series, which it has maintained since the 1980s and provides monthly surface temperature data back to 1880, is provided free. It’s not even a line-item in the GISS budget; Schmidt says it comes out of general operating expenses.

And GISS continues to be one of, if not the most, influential organizations in the field, Schmidt argues, because it’s cutting edge without being rigid. It’s a small, nimble group of roughly 130 researchers without a strict hierarchy, so new ideas and research can quickly be vetted, tested, and applied to the model to improve its accuracy.

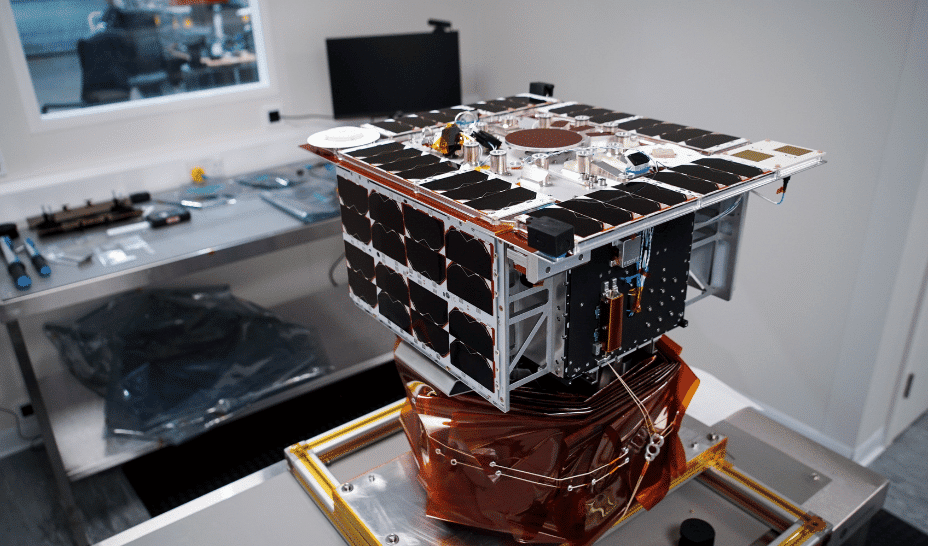

GISS continues to refine and improve its model. Earlier this year, NASA launched a long-delayed satellite project called PACE that will explore phytoplankton growth on the ocean surface, algal blooms and aerosols, and other factors impacting temperature shifts. The institute also remains at the forefront of using machine learning to create models that chart the possible course of climate change.

What happens to this work when GISS leaves the only home it’s ever known remains to be seen. “Obviously, it is not our idea,” Schmidt said, adding that he doesn’t think it’ll save money or lead to increased efficiency. The lease termination notice does say the work will continue in a new home.

“Is this going to impact our mission? Yes, of course,” he said.

Schmidt has made some progress in his search for a new location, but he’s far from finished. He’s essentially begging for desks in the neighborhood, looking to find a home at Columbia University, New York University, or the Natural History Museum. He doesn’t have any budget, so he can’t pay rent and he fears there’s a limit to how generous people will be.

“If you want to bring in people who are going to have interesting ideas and who are going to pursue those ideas, they have to have freedom to do so,” he said. “They can’t be so drowned with proposal writing or doing operational stuff or having to do some bullshit thing for somebody else. If you want to keep the smart people and creative people, you have to give them autonomy.”