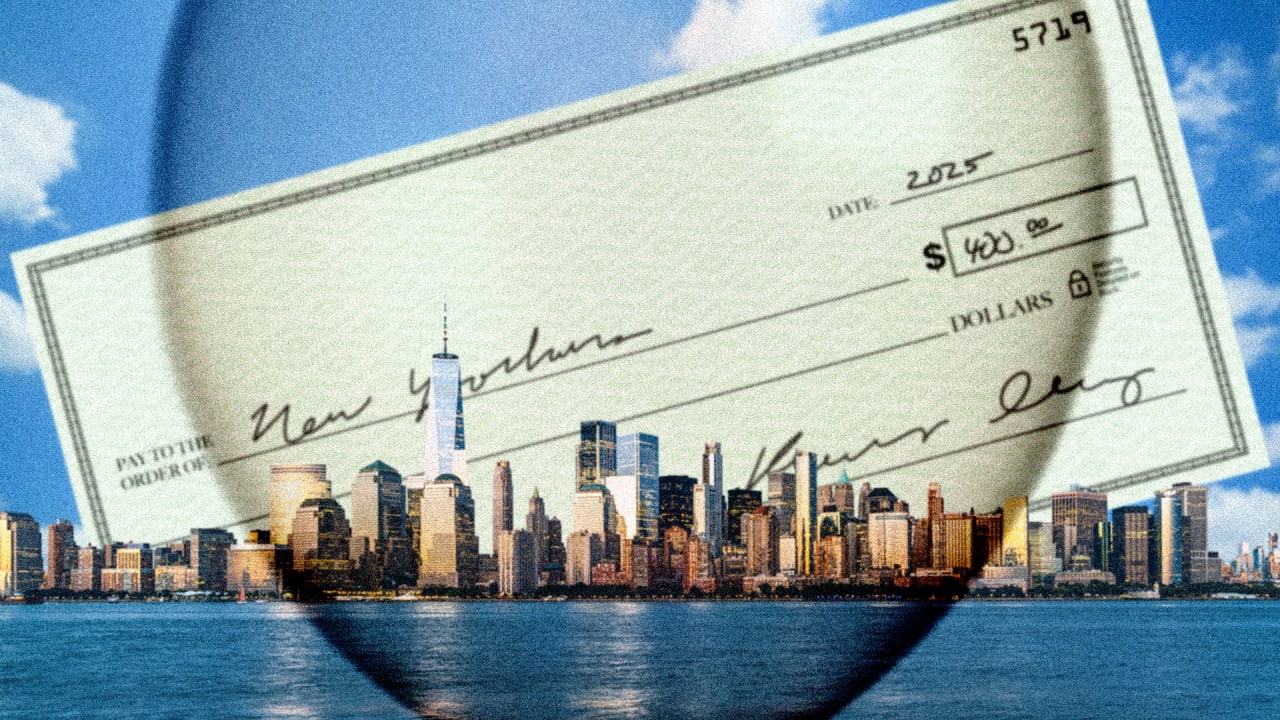

Americans rushing to buy cars might get stuck with high interest rates and bad loan terms

As President Donald Trump’s auto tariffs go into effect, about 20% of car loans are now for seven-year terms, according to Edmunds.

- Americans are flocking to car dealerships before President Donald Trump’s auto tariffs lead to higher vehicle costs. But contending with expensive vehicles and high interest rates, consumers may not be financially equipped to make these big-ticket purchases, leading them to default on debts down the line—or give up vacations and other purchases to offset the impact of the loan.

New car buyers looking to dodge auto tariffs may suffer an unintended financial consequence as a result of lengthy loan terms and high interest rates.

President Donald Trump’s 25% auto tariff introduced in late March has caused a frenzy of new car purchases in the U.S. But as a result of these big-ticket purchases, new car buyers may be taking out loans that take longer to pay off and have higher interest rates than if they were to wait to purchase a vehicle.

Even before Trump’s auto tariffs threatened to hike prices of automobiles and insurance alike, car prices were already high as a result of the pandemic—nearing $48,000 for an average transaction price, per car shopping website Edmunds. With interest rates hovering above 7%, buying a car usually requires borrowing a good chunk of change, Jessica Caldwell, Edmunds head of insights, told Fortune.

To mitigate these steep prices, Americans are extending the length of their loans, with about 20% of car loans now on seven-year terms, according to Edmunds. The consequence for consumers may be that in the rush to dodge tariff-induced price hikes, they’ve saddled themselves with a greater financial burden.

“People are quick to buy something right now because they know that there's a timeline associated with this,” Caldwell said. “The real risk for a lot of folks is they're getting into a car that maybe they weren't necessarily ready to purchase or they purchased a bit earlier and kind of made a snap decision. They could be signing up for unfavorable loan terms or monthly payments that seem difficult.”

The inevitability of raised auto prices

Car dealerships have seen a flurry of activity as consumers race to find a new vehicle before they bring more extensive, tariffed cars to their lots. Hyundai reported its best-ever April sales, seeing a 19% year-over-year increase, while Nissan likewise saw year-over-year U.S. sales grow 10% in March. Light truck and SUV sales in March and April saw annual sales rates of more than 17 million, respectively, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis’s data on seasonally adjusted vehicle sales. In the same months the year before, the annual rate was around 16 million.

According to Kishore Kulkarni, a professor of economics at the Metropolitan State University of Denver, this trend is justified: Purchasing a new car to dodge tariffs makes financial sense for many.

“We are almost guaranteed to see an increase in price in the future,” Kulkarni told Fortune. “And if you are ready to buy a car, then you better buy it today.”

Indeed, car prices have remained steady year-over-year according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Price Index, but are still about $9,000 more expensive than they were before the pandemic. Although Trump has eased the impact of auto tariffs by rolling back taxes on certain imported auto parts, consumers should still expect to see price tags increase as a result of the tariffs, according to Jason Miller, associate professor of supply chain management at Michigan State University’s Broad College of Business. With car dealership profit margins so thin, they don’t have a choice but to raise prices.

“There's no way, given their margins have fallen back to where they were before COVID, on absolute terms, that they can essentially absorb higher costs of tariffs and not pass a good share of that onto the buyer,” Miller told Fortune.

While new car owners may be avoiding the headache of tariffs, they aren’t free from financial risks. Less-than-ideal loan terms could lead to an individual owing more for the car than its actual value, or negative equity, making it harder to trade it in down the line. Negative equity shares, or the percentage of borrowers who owe more than their car is worth, increased by 0.4% in March, according to data from Cox Automotive, suggesting an increase in default rates in the future.

The movement around tariffs also puts dealers in a challenging position, Edmunds’ Caldwell said. With so much uncertainty about how long tariffs will be in place, dealers may be reluctant to accept trade-ins. They may buy the cars at a high price due to tariff-related price hikes, only for the taxes to no longer be relevant by the time they resell the car—likely costing them thousands.

Financial trade-offs

The hasty decision to make a big-ticket purchase has ripple effects on one’s finances. In order to offset the impact of auto loans on one’s budget, consumers will likely be pinching pennies on other purchases, Kulkarni said. For higher-income Americans, this could look like opting out of vacation plans. For lower-income families, this could mean scaling back on food or clothing purchases.

Consumers may also have to make a longer-term trade off. Recent car buyers made the choice to pay a higher interest rate on a vehicle now instead of waiting for rates to decrease and then refinance those loans, Miller said. But interest rates are likely to stay the same. By the time they are low enough to refinance with more favorable terms, consumers will likely have bigger financial problems.

“[The Federal Reserve] would have incredibly good confidence that either these tariffs are not inflationary as believed, or until they see evidence that the economy is slowing down so much that they need to do something,” Miller said. “And unfortunately, at that point, that usually means that we're going into a recession.”

Despite these risks, with interest rates unlikely to drop anytime soon—and the cost of new cars inevitably rising in the coming months—Caldwell said if she were in the position of many Americans in search of a new car, she would be among the crowds at dealerships.

“The motivations of buying a car are very different from anything else,” she said. “When people need a car, they need a car.”

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com