We both froze while giving TED Talks. Here’s what it taught us about vulnerability

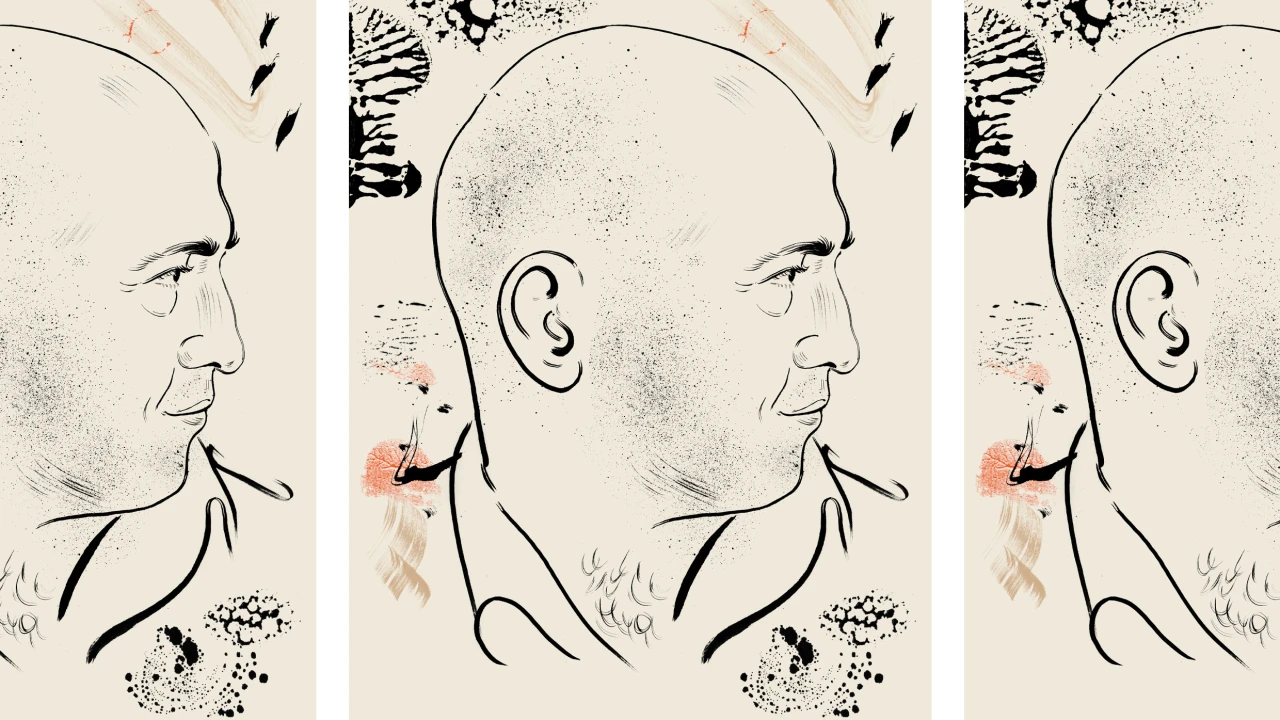

There we were: two experienced professionals, each standing on the iconic red dot of our own TEDx stages, ready to deliver what we hoped would be the most impactful talks of our careers. For Jamie, her meticulously rehearsed opening line—the one she practiced 327 times in the shower, in the mirror, and in front of a very patient partner—evaporated the moment the spotlight hit. Hundreds of expectant eyes waited as the silence stretched . . . and stretched. “Oh @*#%,” she whispered—into the mic. What was meant to be a private moment of panic turned into a public announcement. But instead of recoiling, the audience leaned in. Scott was one minute and fifty seconds into his carefully choreographed talk when he realized the slide clicker—his lifeline—wasn’t in his hand. It was backstage. As his partner began to talk, he edged off the red dot, sliding sideways like what he now calls “a nervous crab doing the walk of shame under a spotlight.” What could have been a disaster became an unexpected moment of relatability. What should have been our most cringeworthy professional moments instead became our most powerful points of connection. Who gets to make mistakes After Jamie’s talk, someone approached her saying, “That moment when you paused made your message so human. I was rooting for you!” “When you had to edge off the stage,” an executive told Scott afterward, “I immediately felt I could relate to you. It was like watching a high-stakes version of that dream where you show up to work without pants.” The revelation hit us both like a thunderbolt: Our supposed failures weren’t failures at all. They were our strongest connection points. All those hours spent practicing perfect delivery? Not wasted time at all, because we were able to recover. But the unplanned human moments? Pure gold. It’s worth acknowledging, however, that our positive experiences with vulnerability came from positions of established credibility. As seasoned professionals with certain privileges, we could afford these momentary lapses without severe consequences. But we also know that vulnerability’s impact varies dramatically depending on who you are and the context in which you’re operating. The Paradox of Leadership We’re often taught that leadership means projecting flawless competence, credibility, and charisma. However, what social psychologists call the “pratfall effect”—a phenomenon documented by Elliot Aronson in 1966—shows that competent people become more likable when they make small mistakes. In other words, the occasional face-plant makes you more relatable. But there’s a critical caveat that Aronson himself emphasized: This effect primarily works for those already perceived as highly competent. For those still establishing credibility—particularly women, people of color, and others from underrepresented groups—the same “charming” mistake can reinforce negative stereotypes and undermine authority. As TED speakers, we had the freedom to make mistakes, which actually increased our likability and connection with the audience without compromising our credibility. In our work with executives, we’ve seen this paradox play out repeatedly. We’ve seen repeatedly that established leaders who initially resist showing any vulnerability find their influence dramatically increases after sharing natural imperfections. Yet for emerging leaders or those from marginalized backgrounds, the calculus is far more complex. It’s essential to acknowledge that the luxury of vulnerability isn’t equally distributed. For women in male-dominated fields, research shows that displays of emotion or uncertainty can trigger harsher judgment than for their male counterparts. For people of color, vulnerability can collide with pernicious stereotypes, reinforcing biases rather than building connection. And for those earlier in their careers or from less privileged backgrounds, the margin for error is often vanishingly small. Alison Fragale’s recent research in her book Likable Badass reveals that leaders face a fundamental paradox: They need to be both respected for competence and liked for warmth. The most effective leaders—whom she calls “likable badasses”—strategically reveal vulnerabilities while maintaining clear boundaries, creating what she terms “approachable authority.” Yet Fragale also acknowledges that women and people of color often face a much narrower band of acceptable behavior, where too much warmth can undermine perceptions of competence, and too much assertiveness can trigger backlash. The path to becoming a “likable badass” is riddled with structural inequities that demand recognition. Which is why we believe vulnerability—tailored to context—has the potential to be a leadership superpower. The Vulnerability Sweet Spot: A Framework for the Perfectly Imperfect Leader Through trial, error, and sometimes painfully awkward experience, we’ve developed a framework for authentic, courage

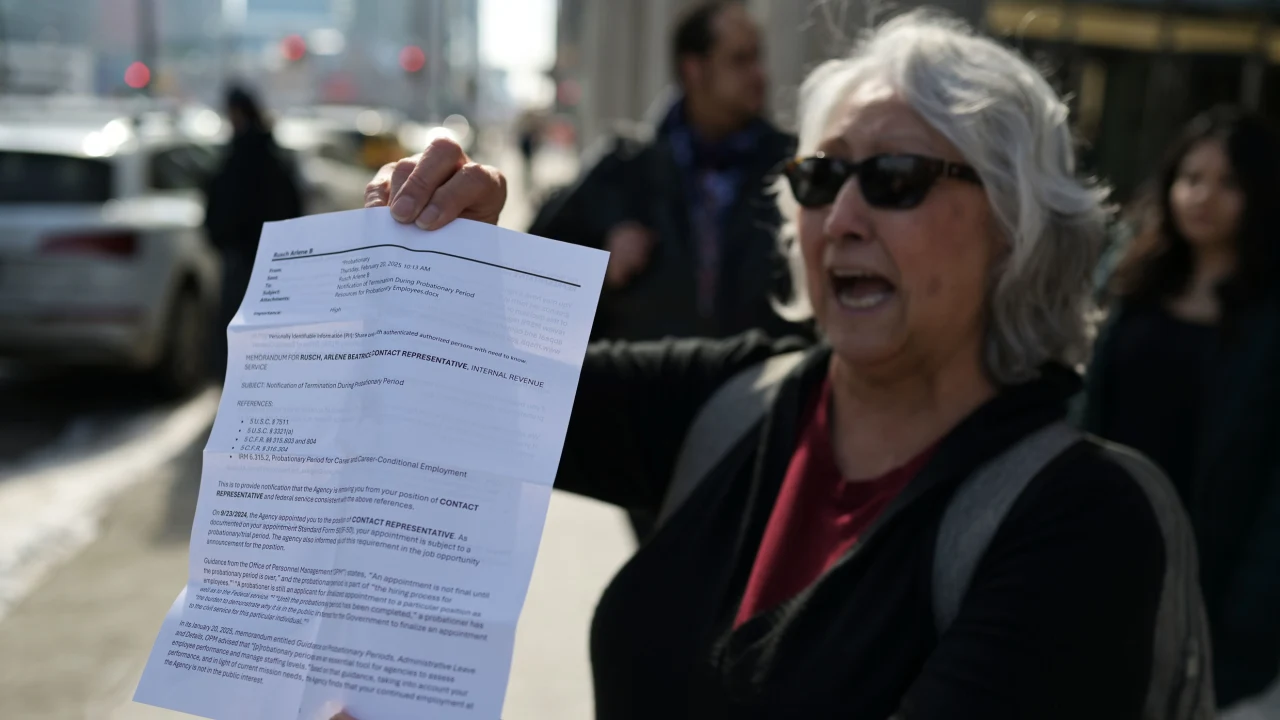

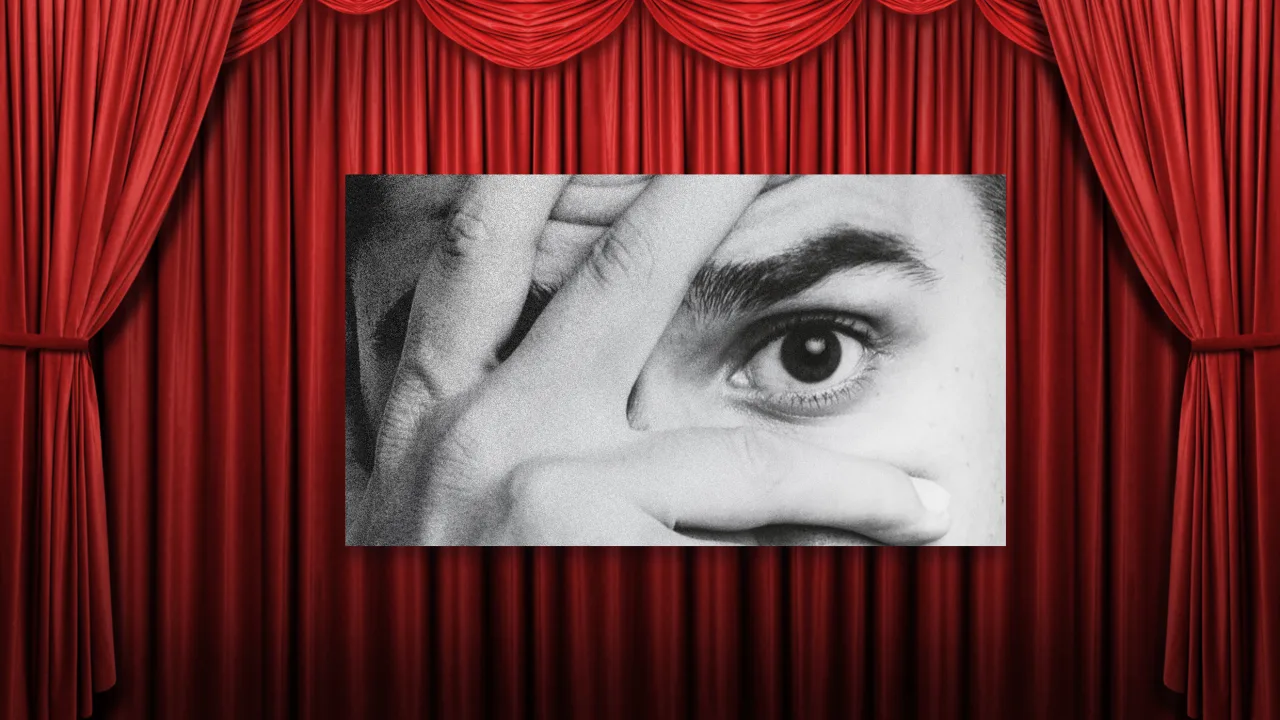

There we were: two experienced professionals, each standing on the iconic red dot of our own TEDx stages, ready to deliver what we hoped would be the most impactful talks of our careers.

For Jamie, her meticulously rehearsed opening line—the one she practiced 327 times in the shower, in the mirror, and in front of a very patient partner—evaporated the moment the spotlight hit. Hundreds of expectant eyes waited as the silence stretched . . . and stretched.

“Oh @*#%,” she whispered—into the mic. What was meant to be a private moment of panic turned into a public announcement. But instead of recoiling, the audience leaned in.

Scott was one minute and fifty seconds into his carefully choreographed talk when he realized the slide clicker—his lifeline—wasn’t in his hand. It was backstage. As his partner began to talk, he edged off the red dot, sliding sideways like what he now calls “a nervous crab doing the walk of shame under a spotlight.” What could have been a disaster became an unexpected moment of relatability.

What should have been our most cringeworthy professional moments instead became our most powerful points of connection.

Who gets to make mistakes

After Jamie’s talk, someone approached her saying, “That moment when you paused made your message so human. I was rooting for you!”

“When you had to edge off the stage,” an executive told Scott afterward, “I immediately felt I could relate to you. It was like watching a high-stakes version of that dream where you show up to work without pants.”

The revelation hit us both like a thunderbolt: Our supposed failures weren’t failures at all. They were our strongest connection points. All those hours spent practicing perfect delivery? Not wasted time at all, because we were able to recover.

But the unplanned human moments? Pure gold.

It’s worth acknowledging, however, that our positive experiences with vulnerability came from positions of established credibility. As seasoned professionals with certain privileges, we could afford these momentary lapses without severe consequences. But we also know that vulnerability’s impact varies dramatically depending on who you are and the context in which you’re operating.

The Paradox of Leadership

We’re often taught that leadership means projecting flawless competence, credibility, and charisma. However, what social psychologists call the “pratfall effect”—a phenomenon documented by Elliot Aronson in 1966—shows that competent people become more likable when they make small mistakes.

In other words, the occasional face-plant makes you more relatable.

But there’s a critical caveat that Aronson himself emphasized: This effect primarily works for those already perceived as highly competent. For those still establishing credibility—particularly women, people of color, and others from underrepresented groups—the same “charming” mistake can reinforce negative stereotypes and undermine authority.

As TED speakers, we had the freedom to make mistakes, which actually increased our likability and connection with the audience without compromising our credibility.

In our work with executives, we’ve seen this paradox play out repeatedly. We’ve seen repeatedly that established leaders who initially resist showing any vulnerability find their influence dramatically increases after sharing natural imperfections. Yet for emerging leaders or those from marginalized backgrounds, the calculus is far more complex.

It’s essential to acknowledge that the luxury of vulnerability isn’t equally distributed. For women in male-dominated fields, research shows that displays of emotion or uncertainty can trigger harsher judgment than for their male counterparts. For people of color, vulnerability can collide with pernicious stereotypes, reinforcing biases rather than building connection. And for those earlier in their careers or from less privileged backgrounds, the margin for error is often vanishingly small.

Alison Fragale’s recent research in her book Likable Badass reveals that leaders face a fundamental paradox: They need to be both respected for competence and liked for warmth. The most effective leaders—whom she calls “likable badasses”—strategically reveal vulnerabilities while maintaining clear boundaries, creating what she terms “approachable authority.”

Yet Fragale also acknowledges that women and people of color often face a much narrower band of acceptable behavior, where too much warmth can undermine perceptions of competence, and too much assertiveness can trigger backlash.

The path to becoming a “likable badass” is riddled with structural inequities that demand recognition. Which is why we believe vulnerability—tailored to context—has the potential to be a leadership superpower.

The Vulnerability Sweet Spot: A Framework for the Perfectly Imperfect Leader

Through trial, error, and sometimes painfully awkward experience, we’ve developed a framework for authentic, courageous leadership that we now share with executives who are tired of the exhausting perfectionism treadmill. But we emphasize that this framework must be applied with careful attention to context, power dynamics, and the unique challenges faced by those with marginalized identities:

1. Create intentional “vulnerability loops”

Ed Catmull, Jamie’s former boss and cofounder and former president of Pixar Animation, would often say in meetings “I’m wrong more than half the time.” That simple phrase created what Harvard professor Jeff Polzer calls a “vulnerability loop”—inviting reciprocal openness that builds trust faster than a box of free donuts in the break room. By modeling approachable authority, he cultivated psychological safety that fueled Pixar’s creative engine.

But we’ve observed that this same approach can backfire for leaders without Catmull’s established positional power and reputation. For a woman leading a male-dominated team or a person of color in a predominantly white organization, admitting uncertainty might inadvertently reinforce harmful stereotypes about competence. The lesson? Sometimes the most powerful thing a well-established leader can say is “I have no idea what I’m doing right now.” But for others, strategic vulnerability requires careful calibration.

2. Transform mistakes into growth narratives

Scott had prepared meticulously for his courage workshop with a large government leadership team—but within minutes, he realized he’d misread the room. His agenda assumed participants would willingly engage, but the energy was brittle. The stress was high, morale was low, and the silence hung heavy.

Then something unexpected—and unscripted—happened.

The chief elected official chose to speak first. But instead of safe, ceremonial words, he paused, and shared a specific fear he was facing in that moment as a leader.

The room shifted. Silence held for a beat. Then, one by one, others began to speak—naming real fears, deeper commitments, and the tensions they’d been carrying alone. That moment of unrehearsed vulnerability didn’t fix everything. But it disrupted the silence, reset the tone of leadership, and sparked the psychological safety needed for meaningful change to begin.

3. Create structural support for imperfection

Pixar holds rigorous postproduction reviews that deliberately focus on uncovering mistakes—despite the very human tendency to celebrate victories and immediately start stressing about the next project. The process norms prevent individual blame, instead promoting shared responsibility for both successes and improvements. At its heart, the process embraces the principle that imperfection, continuous learning, and growth form the foundation of great filmmaking.

By creating formal structures to examine what didn’t work, the studio transforms potential failures into catalysts for innovation. When failure analysis becomes collective rather than personal, it creates safer spaces for those who might otherwise face disproportionate consequences for acknowledging mistakes.

4. Create equitable spaces for vulnerability

At Pixar, Jamie codesigned a Mutual Mentorship Program specifically designed to address power imbalances. Over six months, senior mentors and junior mentees built relationships by exchanging responses to questions like, “Share a pivotal time that created anxiety but informs who you are today.”

This structured approach produced two remarkable outcomes. First, mentors gained genuine insight into the dramatically different experiences of those with less organizational power. Many left the program as vocal advocates for their mentees, having seen firsthand the additional barriers they navigated.

Second, mentees formed a powerful coalition where they could practice speaking up authentically. Through monthly discussions about power dynamics and calculated risk-taking, they developed both individual confidence and collective strength—transforming vulnerability from a personal liability into a shared asset.

5. Know your audience

Before revealing vulnerability, assess the terrain carefully. Do your colleagues and superiors already view you as competent? Do they genuinely care about your success? While it’s ultimately leaders’ responsibility to make workplaces safe for authenticity, we must acknowledge that not all environments offer this security.

For those still establishing credibility—especially individuals from underrepresented backgrounds—the most courageous act might be a carefully timed truth or a question that invites others in. Even micro-moments, like asking a powerful question for honest feedback in a team setting or naming a challenge with curiosity rather than certainty, can plant the seeds of strategic vulnerability. These moments may not be headline-worthy, but over time, they build trust, credibility, and voice.

If you determine that sharing vulnerably carries too much risk in your current position, remember that choosing to strategically present yourself isn’t “fake”—it’s a legitimate form of self-protection. The calculation is intensely personal: What are the costs of being real versus the costs of maintaining a more guarded professional persona? There’s no universal right answer, only the one that serves your well-being and advancement in your specific context.

The Real Leadership Superpower

Our TED experiences taught us that leadership impact doesn’t come from flawless performance, but from authentic human connection. The moments that feel most vulnerable—when your mind goes blank during a presentation or when you have to admit you have no idea how to solve a problem—are precisely where your most meaningful leadership happens.

The next time you feel that urge to appear perfect, remember: Your most authentic moment might be waiting on the other side of what feels like failure. In a world increasingly dominated by curated personas and polished images, authentic vulnerability can be a powerful differentiator, but also a risk that varies dramatically depending on who you are.

After all, nobody roots for the superhero who never breaks a sweat. We root for the one who gets knocked down, mutters something slightly inappropriate, and then gets back up again with a knowing smile.

But we must also work toward a world where all leaders, regardless of their identity, have the freedom to be imperfectly human without disproportionate penalties.