Trump’s EPA wants to weaken rules on forever chemicals. It legally can’t—but that doesn’t mean your drinking water is safe

There’s a good chance that your drinking water contains forever chemicals. PFAS, the type of chemicals used in products like some nonstick pans and waterproof jackets, is present in water systems for nearly half of Americans. But the Trump administration now wants to roll back Biden-era rules that would have cleaned up certain types of the chemicals. There’s a catch: an “anti-backsliding” provision in the Safe Drinking Water Act says that any new standard for drinking water safety can’t be less protective than the old standard. “The provision is really simple,” says Dave Owen, a professor at the University of California College of the Law in San Francisco. “The only way they could get around it is to say we have discovered new evidence that clarifies that revising the standard will do nothing to reduce protection of public health. And I’d be shocked if they have evidence that would substantiate that claim.” In 2024, the Biden-era EPA issued a rule with new limits for six types of PFAS (or “per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances”), which have been linked to cancer and developmental problems. Under the rule, public water utilities have to monitor water for the six compounds, notify the public of unsafe levels, and treat the water. The rule gave them until 2027 to comply, though it allowed for an extension of an extra two years because of the expense of setting up new treatment systems. This week, the EPA announced that it would rescind the rule for four of the PFAS types on the list (known as PFHxS, PFNA, HFPO-DA or GenX, and PFBS). For two others—PFOA and PFOS—it would delay the requirement for utilities to comply. EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin claimed that the agency didn’t necessarily want to weaken the limits for the four chemical compounds, just “reconsider” the rule. (To try to make a change, they’ll also have to go through a long rulemaking process—they can’t simply get rid of the rule automatically.) But water utilities and the chemical industry have been fighting to get rid of the limits, and said the administration’s announcement was a step in the right direction. If the EPA does eventually attempt to loosen the limits, environmental groups could sue under the anti-backsliding provision. There’s clear evidence that the compounds aren’t safe for people’s health. “There are literally hundreds of studies that show that these chemicals are dangerous,” says Erik Olson, senior strategic director for health at NRDC. “The evidence is very strong. That’s why EPA issued those regulations.” In the case of the other two compounds, Olson says the EPA can’t legally extend the deadline for utilities to comply. The Safe Drinking Water Act allows for a maximum of five years for utilities to meet new requirements, and that’s already in place. An EPA spokesperson said that the agency would “follow the legal process laid out in the Safe Drinking Water Act.” But even though the rules are still in place, and the administration shouldn’t be able to roll them back, the current situation means that utilities are likely to delay progress. (The administration has also made it clear that it’s willing to disregard laws.) “It creates a lot of confusion when you’re a water utility,” Olson says. “Utilities get five years to comply because they have to have contracts. They have to get funded. They have to do all this stuff in order to build a treatment plant. And if a utility senses, oh, I may not have to do this, are they going to invest in a new water treatment plant to protect their customers? Or are they going to wait and see and hope that EPA isn’t going to enforce some of these rules?” There’s also a risk, he says, that utilities might invest in treatment systems that only work for PFOA and PFOS, the two older types of “long-chain” PFAS. Those chemicals have mostly been phased out and replaced by newer types of PFAS. Some treatments for PFOA don’t work for newer types of the chemicals. That’s another fundamental problem with the regulation in the first place: There are thousands of different varieties. As certain types get regulated, the industry replaces them with others that often are just as risky. The chemicals should be regulated as a class, rather than by specific type, Olson says. “Big manufacturers in the U.S. agreed to phase out their manufacturer [PFOA and PFOS] many years ago,” he says. “But what they did is they just had ‘regrettable substitutions,’ as we call them. Other new ones popped up, like Gen X . . . It’s a classic [situation] where a chemical company stops making one thing and just jumps to the next.” Water utilities are fighting the rules because of cost. But funding exists for cleanup, including $9 billion in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and $12.5 billion in a settlement with chemical manufacturers last year. “There’s $21-plus billion that’s sitting there,” Olson says. Under Biden, the EPA had estimated that PFAS treatment would cost utilities around $1.5 billion

There’s a good chance that your drinking water contains forever chemicals. PFAS, the type of chemicals used in products like some nonstick pans and waterproof jackets, is present in water systems for nearly half of Americans. But the Trump administration now wants to roll back Biden-era rules that would have cleaned up certain types of the chemicals.

There’s a catch: an “anti-backsliding” provision in the Safe Drinking Water Act says that any new standard for drinking water safety can’t be less protective than the old standard.

“The provision is really simple,” says Dave Owen, a professor at the University of California College of the Law in San Francisco. “The only way they could get around it is to say we have discovered new evidence that clarifies that revising the standard will do nothing to reduce protection of public health. And I’d be shocked if they have evidence that would substantiate that claim.”

In 2024, the Biden-era EPA issued a rule with new limits for six types of PFAS (or “per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances”), which have been linked to cancer and developmental problems. Under the rule, public water utilities have to monitor water for the six compounds, notify the public of unsafe levels, and treat the water. The rule gave them until 2027 to comply, though it allowed for an extension of an extra two years because of the expense of setting up new treatment systems.

This week, the EPA announced that it would rescind the rule for four of the PFAS types on the list (known as PFHxS, PFNA, HFPO-DA or GenX, and PFBS). For two others—PFOA and PFOS—it would delay the requirement for utilities to comply.

EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin claimed that the agency didn’t necessarily want to weaken the limits for the four chemical compounds, just “reconsider” the rule. (To try to make a change, they’ll also have to go through a long rulemaking process—they can’t simply get rid of the rule automatically.) But water utilities and the chemical industry have been fighting to get rid of the limits, and said the administration’s announcement was a step in the right direction.

If the EPA does eventually attempt to loosen the limits, environmental groups could sue under the anti-backsliding provision. There’s clear evidence that the compounds aren’t safe for people’s health. “There are literally hundreds of studies that show that these chemicals are dangerous,” says Erik Olson, senior strategic director for health at NRDC. “The evidence is very strong. That’s why EPA issued those regulations.”

In the case of the other two compounds, Olson says the EPA can’t legally extend the deadline for utilities to comply. The Safe Drinking Water Act allows for a maximum of five years for utilities to meet new requirements, and that’s already in place.

An EPA spokesperson said that the agency would “follow the legal process laid out in the Safe Drinking Water Act.”

But even though the rules are still in place, and the administration shouldn’t be able to roll them back, the current situation means that utilities are likely to delay progress. (The administration has also made it clear that it’s willing to disregard laws.) “It creates a lot of confusion when you’re a water utility,” Olson says. “Utilities get five years to comply because they have to have contracts. They have to get funded. They have to do all this stuff in order to build a treatment plant. And if a utility senses, oh, I may not have to do this, are they going to invest in a new water treatment plant to protect their customers? Or are they going to wait and see and hope that EPA isn’t going to enforce some of these rules?”

There’s also a risk, he says, that utilities might invest in treatment systems that only work for PFOA and PFOS, the two older types of “long-chain” PFAS. Those chemicals have mostly been phased out and replaced by newer types of PFAS. Some treatments for PFOA don’t work for newer types of the chemicals.

That’s another fundamental problem with the regulation in the first place: There are thousands of different varieties. As certain types get regulated, the industry replaces them with others that often are just as risky. The chemicals should be regulated as a class, rather than by specific type, Olson says.

“Big manufacturers in the U.S. agreed to phase out their manufacturer [PFOA and PFOS] many years ago,” he says. “But what they did is they just had ‘regrettable substitutions,’ as we call them. Other new ones popped up, like Gen X . . . It’s a classic [situation] where a chemical company stops making one thing and just jumps to the next.”

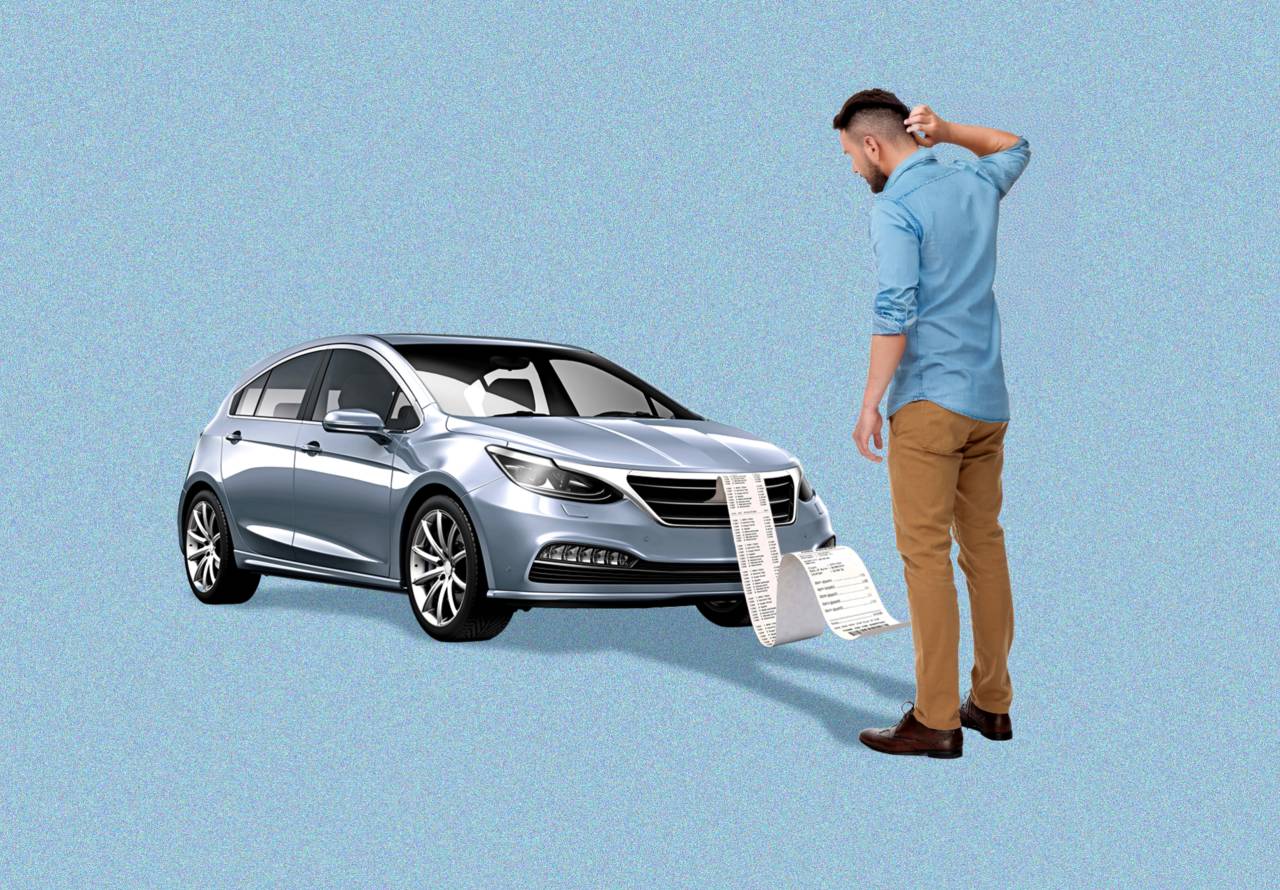

Water utilities are fighting the rules because of cost. But funding exists for cleanup, including $9 billion in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and $12.5 billion in a settlement with chemical manufacturers last year. “There’s $21-plus billion that’s sitting there,” Olson says. Under Biden, the EPA had estimated that PFAS treatment would cost utilities around $1.5 billion a year, though other estimates range up to $3.8 billion a year. “If the utilities want to go ahead and start building this treatment technology, they should be asking for that money, rather than dragging their feet,” he says. “If you think about it, what is a water utility’s job? They have one job. And that is to supply adequate, safe water to consumers. And they’re just fighting, kicking, and screaming, against doing that.”

![[Weekly funding roundup May 10-16] Large deals remain a no-show](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/220356402d6d11e9aa979329348d4c3e/Weekly-funding-1741961216560.jpg)

![Epic Games: Fortnite is offline for Apple devices worldwide after app store rejection [updated]](https://helios-i.mashable.com/imagery/articles/00T6DmFkLaAeJiMZlCJ7eUs/hero-image.fill.size_1200x675.v1747407583.jpg)

.jpg)