How to use ‘propagandart’ to sell your ideas

In the mid-1920s, most Americans ate light breakfasts. Edward Bernays, who would eventually be considered the father of public relations, was hired by a company that sold bacon to promote the idea that a “hearty” meal including bacon and eggs was more scientifically beneficial. Bernays conducted interviews and then carefully framed the results that led to a shift in public opinion. America’s iconic breakfast is now bacon and eggs. In the 1950s, the Keep America Beautiful campaign was launched by a coalition of corporations whose products were often littered (soda bottles, plastic packages, etc.). Their iconic moment was 1971’s commercial with actor Iron Eyes Cody as a Native American shedding a single tear about litter and pollution. Both of these campaigns were carefully crafted propaganda designed to focus on individual decisions and actions. They relied on imagery, symbolism, and emotion, not raw facts. And they weren’t designed to explicitly sell bacon or guilt. Public relations storytellers shaped public opinion like artists and nudged enough behavior change that the entire culture was impacted. Artful vision and the power to reframe Propaganda is an idea or allegation crafted not to inform neutrally, but to influence behavior and belief. Art is an object or image shaped with skill and imagination to evoke emotion and meaning. It’s useful to learn from people who create art and propaganda. In my work—planning transportation systems with a bias toward human flourishing—I often say I create “propagandart” to save the human race. prä-pə-ˈgan-därt (noun): ideas, allegations, and aesthetic objects produced with the conscious use of skill and creative imagination, spread deliberately to further one’s cause or to damage an opposing cause The people best equipped to influence behavior aren’t just marketers or policymakers—they’re propagandartists. The photographer who shapes what you notice. The muralist who reclaims public space. The meme creator who distills frustration into a punchline. Each is practicing a form of strategic persuasion. Each is shaping not just what we see, but how we feel about it. Whether you’re pitching a startup, selling a product, or reshaping a city, you’re competing with ads, reels, renderings, memes—all designed to influence perception before you’ve said a word. To win the room, you don’t need new tools nearly as much as you need to master an old one: the art of influence. Consider a fine art photographer and a meme lord. One crafts a single frame with obsessive care; the other floods the internet with viral punchlines. Both are propagandists—storytellers who deliberately shape how we see and feel. If I want to create walk-friendly, bicycle-friendly places that increase the smile density in my city, I’m only going to reach that goal through persuasive storytelling. Every photograph is a lie. Photography isn’t objective. Ansel Adams didn’t just capture Yosemite; he framed it to evoke awe. Gordon Parks didn’t just document injustice; he gave it emotional gravity. What’s left out of the frame is as important as what’s inside it. That’s the lesson: direct attention with intention. Don’t pitch the product. Show the life it makes possible. The relieved parent, the joyful commuter, the profitable small business, etc. Great art doesn’t just show—it sells a version of reality. Remix culture and the new public square For urbanism innovators, shaping imaginations is a vital part of the playbook. Launching a new cargo bike, pitching a housing policy, or designing a bus transfer hub requires persuasion. If you can’t shape public imagination, your product, policy, or vision will be dead on arrival, no matter how brilliant the data behind it. Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party, 1979 on display at the Brooklyn Museum, ca. 2007. [Photo: Stan Honda/AFP/Getty Images] Artists reframe the past, present, and future—sometimes in an effort to change culture in some way, sometimes just to be irreverent or entertaining. From Shepard Fairey’s “Hope” poster to Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party, art can create appetites for ideas the mainstream hasn’t developed yet. A speculative rendering of a car-free downtown is an example of a prompt for belief. The High Line in New York began this way: a vision, illustrated and circulated, that turned an abandoned rail line into a civic treasure. Applying lessons learned from the art world doesn’t require training to become a great artist yourself. Memes are fast, cheap, and culturally potent. They’re the digital age’s most accessible form of propagandart and we all know they can sometimes look sloppy and haphazard. A meme doesn’t explain—it distills. The “Distracted Boyfriend” image reshaped debates about loyalty. Bernie Sanders in mittens became a viral fundraiser. Memes bypass logic, persuading with speed, irony, and emotional friction. For builders and changemakers, memes offer a strategy. Want to communicate the absurdity o

In the mid-1920s, most Americans ate light breakfasts. Edward Bernays, who would eventually be considered the father of public relations, was hired by a company that sold bacon to promote the idea that a “hearty” meal including bacon and eggs was more scientifically beneficial. Bernays conducted interviews and then carefully framed the results that led to a shift in public opinion. America’s iconic breakfast is now bacon and eggs.

In the 1950s, the Keep America Beautiful campaign was launched by a coalition of corporations whose products were often littered (soda bottles, plastic packages, etc.). Their iconic moment was 1971’s commercial with actor Iron Eyes Cody as a Native American shedding a single tear about litter and pollution.

Both of these campaigns were carefully crafted propaganda designed to focus on individual decisions and actions. They relied on imagery, symbolism, and emotion, not raw facts. And they weren’t designed to explicitly sell bacon or guilt. Public relations storytellers shaped public opinion like artists and nudged enough behavior change that the entire culture was impacted.

Artful vision and the power to reframe

Propaganda is an idea or allegation crafted not to inform neutrally, but to influence behavior and belief. Art is an object or image shaped with skill and imagination to evoke emotion and meaning. It’s useful to learn from people who create art and propaganda. In my work—planning transportation systems with a bias toward human flourishing—I often say I create “propagandart” to save the human race.

prä-pə-ˈgan-därt (noun): ideas, allegations, and aesthetic objects produced with the conscious use of skill and creative imagination, spread deliberately to further one’s cause or to damage an opposing cause

The people best equipped to influence behavior aren’t just marketers or policymakers—they’re propagandartists. The photographer who shapes what you notice. The muralist who reclaims public space. The meme creator who distills frustration into a punchline. Each is practicing a form of strategic persuasion. Each is shaping not just what we see, but how we feel about it.

Whether you’re pitching a startup, selling a product, or reshaping a city, you’re competing with ads, reels, renderings, memes—all designed to influence perception before you’ve said a word. To win the room, you don’t need new tools nearly as much as you need to master an old one: the art of influence.

Consider a fine art photographer and a meme lord. One crafts a single frame with obsessive care; the other floods the internet with viral punchlines. Both are propagandists—storytellers who deliberately shape how we see and feel. If I want to create walk-friendly, bicycle-friendly places that increase the smile density in my city, I’m only going to reach that goal through persuasive storytelling.

Every photograph is a lie. Photography isn’t objective. Ansel Adams didn’t just capture Yosemite; he framed it to evoke awe. Gordon Parks didn’t just document injustice; he gave it emotional gravity. What’s left out of the frame is as important as what’s inside it.

That’s the lesson: direct attention with intention. Don’t pitch the product. Show the life it makes possible. The relieved parent, the joyful commuter, the profitable small business, etc. Great art doesn’t just show—it sells a version of reality.

Remix culture and the new public square

For urbanism innovators, shaping imaginations is a vital part of the playbook. Launching a new cargo bike, pitching a housing policy, or designing a bus transfer hub requires persuasion. If you can’t shape public imagination, your product, policy, or vision will be dead on arrival, no matter how brilliant the data behind it.

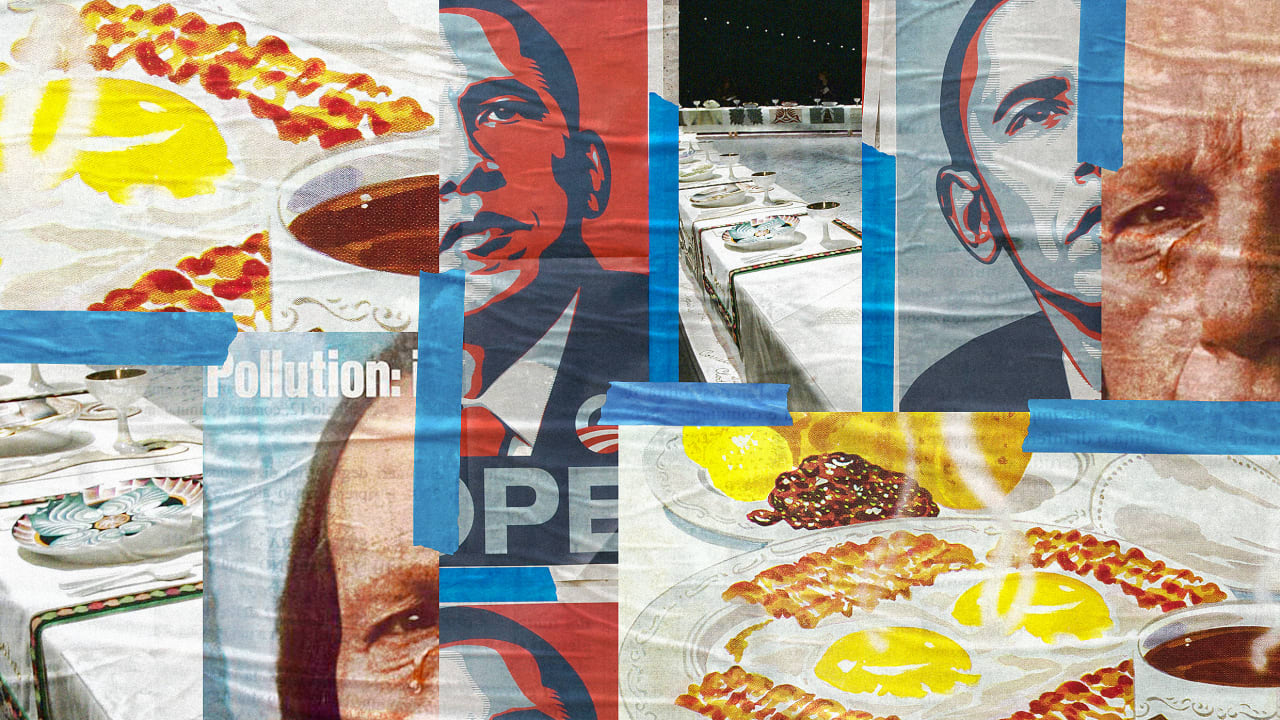

Artists reframe the past, present, and future—sometimes in an effort to change culture in some way, sometimes just to be irreverent or entertaining. From Shepard Fairey’s “Hope” poster to Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party, art can create appetites for ideas the mainstream hasn’t developed yet. A speculative rendering of a car-free downtown is an example of a prompt for belief. The High Line in New York began this way: a vision, illustrated and circulated, that turned an abandoned rail line into a civic treasure.

Applying lessons learned from the art world doesn’t require training to become a great artist yourself. Memes are fast, cheap, and culturally potent. They’re the digital age’s most accessible form of propagandart and we all know they can sometimes look sloppy and haphazard. A meme doesn’t explain—it distills. The “Distracted Boyfriend” image reshaped debates about loyalty. Bernie Sanders in mittens became a viral fundraiser. Memes bypass logic, persuading with speed, irony, and emotional friction.

For builders and changemakers, memes offer a strategy. Want to communicate the absurdity of legacy infrastructure or bloated software? A meme can do in seconds what a slide deck does in 30 minutes. Memes can help energize a movement or reframe a dull category. The trick is to stop thinking of them as fluff and start using them as signals.

Organized persuasion

We’ve been taught to fear the word “propaganda.” But propaganda, at its root, is organized persuasion. And in an environment of infinite messages, intentional persuasion is a competitive edge. Propagandart blends art’s emotional pull with strategy’s clarity. A viral video about your mission is propagandart. A campaign calling out industry greenwashing is propagandart. A cartoon satirizing the way zoning keeps Americans trapped in cars is propagandart.

Decide what belief or point of view you’re trying to implant, or what behavior you’re trying to shift. Then use facts to create stories that move markets.

From canvas to camera to meme, the artist’s role has never changed: shape what people see—and how they feel about it. This is true for shipping code, designing buildings, or launching a movement of kids biking to school. Your work and your legacy lives or dies by stories.

With artistic tools in every pocket and public platforms a click away, we’re in a golden age of propagandart. If you want your idea to stick, it needs more than a data point—it needs to be seen, felt, and shared.

Just ask the campaigners behind Barcelona’s “Superblocks.” Before reconfiguring traffic patterns or drafting ordinances, they shared speculative renderings of tree-lined streets, kids playing in former intersections, and cafes spilling into quiet roads once dominated by cars. Those images didn’t just illustrate the plan. They created public appetite for change—turning skepticism into support.

The power of propagandart is shaping not just what people know, but what they want. Picture a better world. Frame the story. Share it. If you can shape how people feel, you can shape what they demand.

![What Are Website Demographics? [Explained]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/e3/e4/e3e48631e5cd307cd7a4bfee26498e62/0db9c37107a24c016f06d29ca0a5719a/website-demographics-sm.png)