The often invisible difference between working and pretending to work

How can you measure productivity you can’t see? When we try to evaluate whether someone is “killing it” in their role simply by hearing them mansplain their digital transformation strategy or their AI-powered journey of innovation, it’s hard to disentangle facts from fiction, competence from confidence, and talent from, well, BS.The harder it is to decipher what someone is doing, the easier it is to fake it. Ironically, this means that the more you get paid for doing what you do—because specialized skills and in-demand jobs tend to involve operating in abstract, intellectual, and symbolic processes rather than visible, tangible, observable work—the harder it is to know if you are any good at it. Welcome to the modern workplace, where the line between working and pretending to work is not just thin, it’s vanishing. This is particularly true with the advent of AI, which produces content indistinguishable from what humans produce, if not better. If knowledge workers are merely promptly AI and instructing the AI agents to work for them, are humans still working? When work became hard to see One of the great historical transitions in the knowledge economy is that as work became more “intellectual,” it also became less visible. Unlike a farmer’s harvest or a blacksmith’s horseshoe, knowledge work is abstract. You can’t see a PowerPoint deck’s impact (if we could, we would probably not devote so many hours in our life to create slides), or touch a well-formatted spreadsheet (though we can admire it, sure). And when results are ambiguous, evaluations become subjective. More importantly, the connection between the behaviors people perform or display (typing, thinking, reading, writing) and the desirable work or organizational outcomes (growth, productivity, innovation, performance) is invisible, which allows people to brag about their apparent accomplishments on LinkedIn and their resumés: “during my tenure we increased profits by 25%” . . .. because of you, despite you, or coincidentally while you were there? The modern office was once thought to be a factory of ideas, but more often, it is a theater of activity. Slack pings, emails sent at 11:47 p.m., and meetings scheduled for no good reason serve as proxies for productivity. As psychologist Adam Grant noted, we confuse responsiveness with competence. Presence—whether physical or digital—is misread as performance, or even talent. Even performance reviews have become more performative than evaluative. As my colleagues and I have shown, most managers are bad at assessing performance—biased by recent events, likability, and self-confidence. The upshot? It’s easier to reward those who are good at appearing to work than those who are actually working. And our notion of “adding value” is conflated with being rewarding to deal with. Confidence over competence It gets worse. As work becomes more cerebral, we also become better at gaming the system. Impression management has become a meta-skill: not the work itself, but the ability to make others believe that we are working, and working well. This isn’t just anecdotal. Psychological studies repeatedly show that people are poor judges of competence, often mistaking confidence for ability. One study shows that speaking more than others in group settings predicts being selected as leader to that group: Yes, there is an ROI to mansplaining! In fact, in a world where perception trumps reality, those who can tell a compelling story about their work often outperform those who quietly produce real results. This explains why buzzwords thrive in business: “leveraging synergies” sounds more important than “talking to another department.” And therein lies the tragedy: The more time you devote to pretending to work, which by definition decreases the time you can devote to actually working, the more successful you may be in an organizational setting. As our skills evolved to navigate complex knowledge ecosystems, so did our capacity to appear productive. This is a uniquely modern skill, honed through LinkedIn updates, Zoom facial expressions, and the subtle art of replying-all. For all the talks of “authenticity” and being yourself at work, as my upcoming book documents, there is hardly ever a reward for being honest and transparent when you are up against masters of deceptions and deception eclipses reality. Those who confess that they prefer to have their achievements speak for themselves are no doubt noble and ethical—but they will generally go unnoticed compared to people who proactively engaged in politics, self-promotion, and sucking up to their boss. The rise of meaningless work In Bullshit Jobs, the late anthropologist David Graeber describes a category of work so pointless that even the people doing it can’t justify its existence. Entire industries—corporate compliance, middle management, strategic communications—are filled with people who aren’t sure what their job is for, but are sure it r

How can you measure productivity you can’t see? When we try to evaluate whether someone is “killing it” in their role simply by hearing them mansplain their digital transformation strategy or their AI-powered journey of innovation, it’s hard to disentangle facts from fiction, competence from confidence, and talent from, well, BS.

The harder it is to decipher what someone is doing, the easier it is to fake it. Ironically, this means that the more you get paid for doing what you do—because specialized skills and in-demand jobs tend to involve operating in abstract, intellectual, and symbolic processes rather than visible, tangible, observable work—the harder it is to know if you are any good at it.

Welcome to the modern workplace, where the line between working and pretending to work is not just thin, it’s vanishing. This is particularly true with the advent of AI, which produces content indistinguishable from what humans produce, if not better. If knowledge workers are merely promptly AI and instructing the AI agents to work for them, are humans still working?

When work became hard to see

One of the great historical transitions in the knowledge economy is that as work became more “intellectual,” it also became less visible. Unlike a farmer’s harvest or a blacksmith’s horseshoe, knowledge work is abstract. You can’t see a PowerPoint deck’s impact (if we could, we would probably not devote so many hours in our life to create slides), or touch a well-formatted spreadsheet (though we can admire it, sure). And when results are ambiguous, evaluations become subjective. More importantly, the connection between the behaviors people perform or display (typing, thinking, reading, writing) and the desirable work or organizational outcomes (growth, productivity, innovation, performance) is invisible, which allows people to brag about their apparent accomplishments on LinkedIn and their resumés: “during my tenure we increased profits by 25%” . . .. because of you, despite you, or coincidentally while you were there?

The modern office was once thought to be a factory of ideas, but more often, it is a theater of activity. Slack pings, emails sent at 11:47 p.m., and meetings scheduled for no good reason serve as proxies for productivity. As psychologist Adam Grant noted, we confuse responsiveness with competence. Presence—whether physical or digital—is misread as performance, or even talent.

Even performance reviews have become more performative than evaluative. As my colleagues and I have shown, most managers are bad at assessing performance—biased by recent events, likability, and self-confidence. The upshot? It’s easier to reward those who are good at appearing to work than those who are actually working. And our notion of “adding value” is conflated with being rewarding to deal with.

Confidence over competence

It gets worse. As work becomes more cerebral, we also become better at gaming the system. Impression management has become a meta-skill: not the work itself, but the ability to make others believe that we are working, and working well.

This isn’t just anecdotal. Psychological studies repeatedly show that people are poor judges of competence, often mistaking confidence for ability. One study shows that speaking more than others in group settings predicts being selected as leader to that group: Yes, there is an ROI to mansplaining!

In fact, in a world where perception trumps reality, those who can tell a compelling story about their work often outperform those who quietly produce real results. This explains why buzzwords thrive in business: “leveraging synergies” sounds more important than “talking to another department.” And therein lies the tragedy: The more time you devote to pretending to work, which by definition decreases the time you can devote to actually working, the more successful you may be in an organizational setting.

As our skills evolved to navigate complex knowledge ecosystems, so did our capacity to appear productive. This is a uniquely modern skill, honed through LinkedIn updates, Zoom facial expressions, and the subtle art of replying-all. For all the talks of “authenticity” and being yourself at work, as my upcoming book documents, there is hardly ever a reward for being honest and transparent when you are up against masters of deceptions and deception eclipses reality. Those who confess that they prefer to have their achievements speak for themselves are no doubt noble and ethical—but they will generally go unnoticed compared to people who proactively engaged in politics, self-promotion, and sucking up to their boss.

The rise of meaningless work

In Bullshit Jobs, the late anthropologist David Graeber describes a category of work so pointless that even the people doing it can’t justify its existence. Entire industries—corporate compliance, middle management, strategic communications—are filled with people who aren’t sure what their job is for, but are sure it requires a calendar full of meetings.

Consider the following real-but-ridiculous tasks:

- Creating decks to summarize meetings that summarized other decks.

- Emailing to “circle back” on a thread that no one cared about in the first place.

- Editing internal mission statements for tone.

- Filling out time-tracking software to account for the time spent filling it out.

These are not edge cases—they are routine. In a 2015 YouGov poll in the UK, 37% of workers said their job makes no meaningful contribution to the world. That’s not burnout—it’s existential despair.

So, why do these jobs persist? Because they look like work. And if your boss can’t measure your output, they’ll settle for being impressed by your process.

Generative AI and the great illusion of productivity

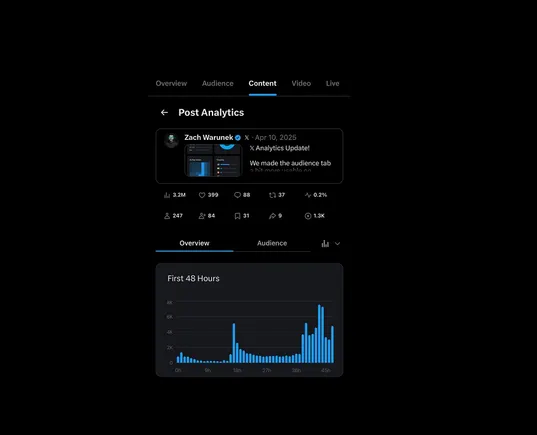

Enter generative AI, the great time-saver of our era. Recent studies suggest that tools like ChatGPT and Claude can reduce knowledge workers’ time-on-task by 40 to 50%, and adoption levels in industrialized countries surpass 75% among knowledge workers. Tasks that once took an hour—writing reports, generating code, crafting marketing copy—can now be done in minutes.

So where are the massive gains in productivity? Spoiler: We haven’t seen them. Not in GDP. Not in total output. Not even in corporate profits. Why? Because productivity isn’t just about output—it’s about input, too.

If you save half your effort but don’t increase your results, you are technically more productive. But you’re also likely spending the freed-up time pretending to still be working, lest your manager start wondering if you were ever that busy to begin with.

And here’s the punchline: The most effective way to boost your productivity is to work less. If your output stays constant, reducing your effort raises your productivity by definition. It’s simple math—and yet deeply counterintuitive in cultures that fetishize hustle and overwork.

The perception trap

Ultimately, success in the modern workplace has less to do with the quality or quantity of your work, and more to do with your ability to persuade others that you’re working. That might sound cynical, but it’s just the logical outcome of environments where real work is hard to measure and soft skills—especially self-promotion—are king.

The tragedy is not that people aren’t working. It’s that we rarely talk about the gap between effort and appearance, between substance and show. Performance has become indistinguishable from performance art.

So, what’s the takeaway? If you’re a leader, measure outcomes—not busyness. If you’re a worker, remember that persuasion matters—but don’t mistake theatrics for impact. And if you’re wondering how to increase your productivity, maybe start by logging off early. You might not get more done—but you’ll definitely become smarter doing less, even if the real talent requires working out how to do something productive with the time you free up, rather than wasting it on social media.

![How to Find Low-Competition Keywords with Semrush [Super Easy]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/73/62/7362f16fb9e460b6d58ccc09b4a048b6/how-to-find-low-competition-keywords-sm.png)