How a Saks Fifth Avenue veteran is doing what many thought impossible: Turning Walmart into a fashion force

Most of Walmart's growth is coming from more affluent shoppers it is trying to lure with more fashion.

For a gathering on the eve of New York’s Fashion Week, the scene in February at a small pop-up store in Manhattan’s SoHo fashionable district was nothing unusual. There were dozens of heavily made-up social media influencers eating canapés and taking selfies, fashion editors asking the designer about his inspiration and executives hoping their new wares will wow the tastemakers who can make or break a new collection.

What made it unusual was this event was for Walmart. The retailer, the world's largest, was showing off new items from the spring drops for its Scoop and Free Assembly brands, two cooler labels it bought in recent years and uses as Trojan horses to build fashion credibility for Walmart overall.

There was a $38 baby blue halter neck dress that would not look out of place at a Hamptons garden party and a $40 linen blend blazer suitable for an office worker. This was a far cry from the $1.99 camis Walmart used to tout on media tours a decade ago, when Walmart’s sole message about its clothes was their low prices.

“We’ve been focused on overhauling the assortment and then changing consumer perception and broadening our customer reach,” Denise Incandela, Walmart U.S.’s executive vice president for fashion told her guests on the sunny winter day in Manhattan. The next day, when the shop opened to the public–it was the first time ever New York City shoppers could buy something in person from Walmart, which has no stores in the city–there were lines around the block in on Wooster Street. Incandela had to have Walmart’s distribution center in Philadelphia send up new inventory twice during the pop-store’s four days, the shop ran out of small sizes and Incandela had to mobilize workers in town from headquarters to help out by folding clothes and stocking shelves.

“We just couldn’t keep up with demand,” Incandela later tells Fortune as she gives a tour of Walmart's store in Secausus, N.J.

That kind of buzz shows Incandela is making inroads with fashion cognoscenti, something that is trickling down to the masses. She has long seen a white space in the apparel market for Walmart between the very cheap clothes it long sold and those offered by department stores, a sweet spot of items priced between $15 and $35. What’s more, Walmart had traditionally focused on the very basics, all but ignoring the rest of a person’s wardrobe. Why let Target have all the fun in the cheap-chic sphere?

“We were really good at socks and underwear, tees and denim but we were not covering 80% of the customer’s closet,” Incandela said. She also noted that it wasn’t just the manager of stores near urban areas, closer to affluent shoppers, that have wanted to stock the more fashion forward stuff. Many of Walmart’s stores in rural areas are “the only game in town” for local shoppers and wanted in too.

Powwows around New York Fashion Week twice a year are hardly their only endeavors. Last year, for instance, its “Style Tour” visited over 40 cities with stylists in tow to inject a sense of being fashionable and fun in a brand which has long been seen as anything but. Years of patience have dented the stigma that long impeded middle and upper middle class shoppers from shopping at Walmart.

Incandela long felt Walmart was leaving a lot of money on the table by not taking advantage of its massive hold on the U.S. consumer. Walmart, as the largest U.S. grocer, gets 150 million visitors a week, with the apparel section right next to the food area, in full view of the most trafficked area of a Walmart. “Why squander that opportunity? They’re here,” she says of those visitors.

'Every time we put stuff on a mannequin, it sells'

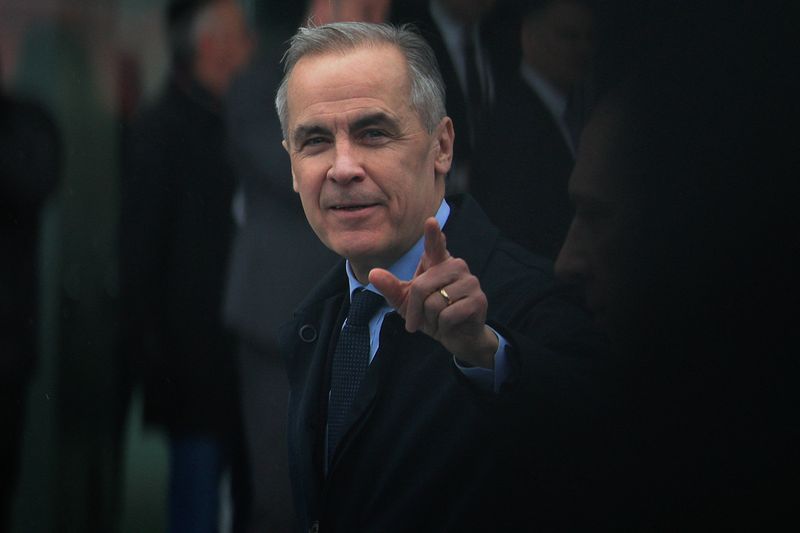

In 2017, Walmart CEO Doug McMillon lured Incandela, a luxury industry veteran with bona fides from years at Saks Fifth Avenue and Ralph Lauren, with the massive assignment of giving Walmart some fashion cred. She first set about moving Walmart away from the “stack-them-high watch them fly” approach to displaying clothes in stores by removing 10% of items on the floor and 10% of the racks to de-clutter the space, and make room for mannequins for visual merchandising of the kind more typical at a Macy’s that at a retailer that follows an “everyday low prices” few-frills philosophy. “Every time we put stuff on a mannequin, it sells,” Incandela, who reports to Walmart U.S.'s chief merchandising officer, Latriece Watkins, says.

Other moves have since included offering more dresses and clothes you can wear to work or to go out, in addition to the string sweatpants Walmart sells in massive quantities.

And while Incandela feels she is only 10% of the way through the big Walmart fashion transformation she has planned, this strategy is already paying off for Walmart as a whole. In its latest earnings report, Walmart, which has been handily outperforming Target, Macy’s and Kohl’s in growth, said that 75% of its growth has been coming from households with more than $100,000 in income or more. “We have people spending $1,000 on a TV or $200 on a KitchenAid appliance and they were leaving the store to buy their fashion,” she says. Coresight Research has estimated Walmart U.S. sold $29.5 billion worth of clothes last year. This week, Walmart is holding its annual investor day in Dallas and will provide an update on its strategy. It remains to be seen whether the Trump tariffs will eventually force Walmart to raise prices on its apparel, though as Fortune detailed last week, the retailer has the clout with suppliers to make them absorb much of the increase.

Nicer but still inexpensive clothing is essential to getting shoppers to spend a little more time in stores, and consequently, spend a little more money. The result is that yes, Walmart still sells those super cheap camis, but it also has 4 clothing brands that take in more than $2 billion a year and another two that do $1 billion to $2 billion. (Target remains a leader here with brands like Cat & Jack that also quickly became multi-billion dollar labels.)

“It was so basic, so volume driven,” says Stacey Widlitz, president of SW Retail Advisors of Walmart’s apparel offering. “They’ve won so much market share by being the inflation buster and consumers have come in thinking, ’I didn’t realize they had some decent fashion.’”

‘It’s going to come down to two companies’

It’s almost incongruous to see someone so stylish and fashion-forward evangelizing with such conviction for Walmart. Incandela, a New Yorker, started in investment banking and then worked as a consultant at McKinsey before entering the world of luxury retail, spending 14 years at Saks and rising as high as chief marketing officer. She later went to Ralph Lauren where she headed its $700 million e-commerce business for 2.5 years. Still today, she loves the world of luxury and will even match a pair of Gucci sneakers with a Scoop blazer she got at Walmart.

The opportunity to build something new, especially inside a gigantic company like Walmart, proved irresistible, and she credits a mentor, the former CEO of Saks, Steve Sadove, for nudging her to take Walmart’s offer in 2017. “He told me, ‘In the end it’s going to come down to two companies and Walmart is one of them. You can either read about it in WWD (a trade publication) or you can be part of it,” she recalled him advising her. What’s more, she relished the opportunity to “serve the 99% of the population versus just the top 10%.”

Turning a brand long associated, and proudly so, with cheap clothing was going to require her to play a very long game. A Walmart effort that preceded her, with a brand called Metro7, proved too expensive for its core shopper but not cool enough for those more affluent customers Walmart coveted. This time Walmart’s approach has been quite different.

In 2019, Walmart bought and relaunched Scoop, which had long enjoyed a following as a niche brand in New York, as its leading store brand for the fashion-forward. Items made of materials like faux fur and vegan leather are all designed to blend stylishness and affordability. The other brand leading Walmart’s so-called "elevated" fashion charge is called Free Assembly, and both labels have been led since 2021 by Brandon Maxwell, a Texas designer who was once Lady Gaga’s fashion director and whose designs can be found at Saks and Neiman Marcus.

Simultaneously, Incandela and her teams have also worked to fix Walmart’s existing brands, many of which frankly were an aesthetic mess. Walmart had been aiming for some fashion credibility before Incandela arrived, but its brands, like menswear brand George, launched in 2018 with showcases in Manhattan, were not catching on.

It can be a bit of a mystery to understand why some store clothing brands are instant hits and others aren’t. A common mistake retailers make is to bring together a collection of clothing and slap a name on it rather than truly build a brand with its own aesthetic and look that can be recognizable across many items.

That was the trap Walmart had fallen into, using up to 15 different manufacturers, designers and color palettes sometimes for products under one brand name. “We’ve hired design teams and we are moving away from ‘Frankensteining’ brands together,” she says.

In-store presentation also left to be desired. For eons, Walmart’s philosophy was that spending money on things like nice shelving and mannequins was a waste of money that curbed its ability to offer the lowest price possible.

About a decade ago, Walmart spent billions redoing its stores, starting with its grocery sections. That involved changes like lowering shelving to increase customer’s line of sight to other areas and using plastic crates that look like wood to showcase fruit and vegetables more appealingly. More recently, many of its stores’ home sections have vignettes to show how a dining table with chairs and dinnerware look together.

For apparel, mannequins appeared, and now suggesting head-to-toe looks have become a fixture at hundreds of Walmart stores. “This is more like a department store in the way that we’re presenting denim,” Incandela tells us on a tour of the Walmart in Secaucus, N.J., one of 815 so-called “stores of the future” with more elevated product presentation that will be eventually rolled out to most the Walmart 4,500-store fleet. It also helps that clothing is neatly folded and stacked in a way that seems beyond the capabilities of some department store chains. And as many other retailers struggle, a number of national brands have begun to appear at Walmart. Reebok for instance now gets the mannequin treatment there.

Incandela was initially hired to oversee Walmart’s online fashion offering. Now, Walmart is the second biggest e-commerce player in the U.S., after Amazon. And online, Walmart can cast a much wider net than it can in-stores where space is ultimately limited and offer items likely too high end for stores but that help build a fashion aura, such as Michael Kors. (Walmart famously made waves this year when an $80 “Wirkin” knock-off of the Hermès’ Birkin bag, was selling on its marketplace via a third-party seller. It is also selling real ones for upwards of $25,000.) Walmart isn’t done testing how high it can go with its assortment. “We sell $20,000 bags and diamonds, so for Walmart from a fashion point of view, we can go very high,” she says.

As we continue the tour of the Secaucus store, Incandela occasionally takes photos of items of something she sees that she doesn’t quite like, whether how a dress is presented or how neat a shelf is, and sends them to someone on her team. Her relentless perfectionism has gotten Walmart this far, but with 90% of the transformation in front of her, in her eyes, she is not about to let up now.

On her to-do list are things like lining up more national brands like Reebok and Madden, continuing to revitalize store brands such No Boundaries which with years of neglect had ended up having an average customer age of 55. Incandela also wants to explore newer-to-Walmart fashion areas like swimwear. But to get there, she’ll continue to show a mix of urgency and caution, and, to long-time Walmart customers, deference.

“If you move too quickly, you risk alienating your core customer and you don’t capture the new customer,” says Incandela.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

![How to Find Low-Competition Keywords with Semrush [Super Easy]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/73/62/7362f16fb9e460b6d58ccc09b4a048b6/how-to-find-low-competition-keywords-sm.png)