Under Armour designed a plant-based clothing line that you can bury in your backyard

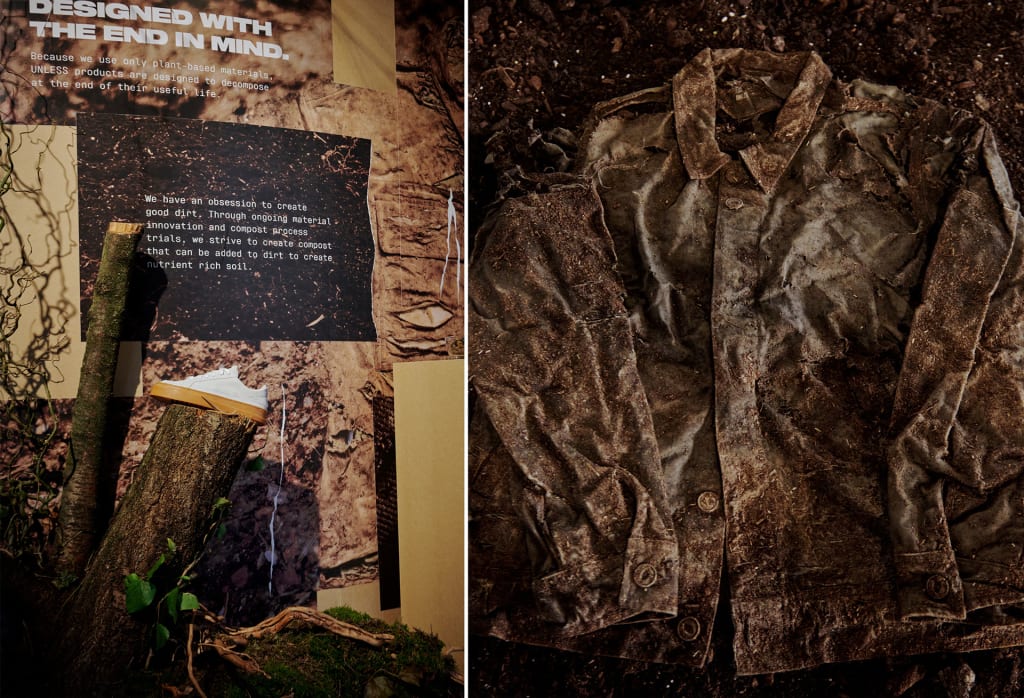

It would seem unlikely for clothing designers get their wheels turning by thinking about what happens to garments when people are through with them. But that’s exactly the sort of backward thinking that led to Under Armour’s new “regenerative sportswear collection,” created in collaboration with Portland, Oregon-based Unless Collective. The collection, which is making its debut in Italy this week during Milan Design Week, comprises footwear and clothing made entirely from plants and plant-based materials. That means they’re biodegradable and compostable. “All of our products make good dirt,” says Eric Liedtke, Unless co-founder & Under Armour EVP of brand strategy, who spoke with Fast Company from Milan. Unless was acquired by Baltimore-based Under Armour last summer, and Liedtke says that it’s allowed Unless to tap into Under Armour’s large base of resources and partnerships to expand its offerings and development operations—the new “regenerative” collection is the result. “We’re here to introduce the idea of regenerative fashion,” he says. “What we mean is that things come from plants and minerals, natural materials, and then go back to being natural materials . . . When you’re ‘regenerative,’ you add value back to the ecosystem, rather than being destructive.” Liedtke says that 70% of clothing is created from “petroleum-based feedstock,” mostly various types of plastics, which never completely vanish or go away—they break down into microplastics and end up in the food and water supply. But his new clothing line does break down and go away; once you’re through with one of Unless’s garments, for instance, you can bury it in your backyard garden, and it’ll compost away. In an industrial composter, an Unless tee shirt will decompose within weeks. [Photos: Under Armour] The new collection features shoes, jackets, vests, shirts, and more that are made from a variety of plant materials. For instance, shoe liners and soles are made from coconut husks and natural rubber latex, buttons are made from corozo nuts, Kapok cotton is used for insulation in vests and jackets, while cotton remains a staple for shirts and other garments. Liedtke says that the garments are built to last, too, and could be compared to products from companies like Russell, Champion, Carhartt, or Dickies. And for those worried about their clothes decomposing while they sit in a dresser, he says not to worry: It takes very specific conditions to initiate the composting process—conditions hopefully not present in the typical closet or bedroom. The collection is meant to be provocative, in some ways, and bring attention to the pollution that modern fashion and clothing manufacturing produces. In that way, it’s not too different from how companies like Beyond Meat and Impossible Meat disrupted the meat industry, or how EVs have shaken up the auto market in recent years. Liedtke hopes that at least some clothing manufacturers will follow suit and start using more natural materials, rather than plastics, to cut down on waste and pollution. “The future is regenerative,” he says. “The question now is scaling it, and telling people about it.”

It would seem unlikely for clothing designers get their wheels turning by thinking about what happens to garments when people are through with them. But that’s exactly the sort of backward thinking that led to Under Armour’s new “regenerative sportswear collection,” created in collaboration with Portland, Oregon-based Unless Collective.

The collection, which is making its debut in Italy this week during Milan Design Week, comprises footwear and clothing made entirely from plants and plant-based materials. That means they’re biodegradable and compostable.

“All of our products make good dirt,” says Eric Liedtke, Unless co-founder & Under Armour EVP of brand strategy, who spoke with Fast Company from Milan.

Unless was acquired by Baltimore-based Under Armour last summer, and Liedtke says that it’s allowed Unless to tap into Under Armour’s large base of resources and partnerships to expand its offerings and development operations—the new “regenerative” collection is the result. “We’re here to introduce the idea of regenerative fashion,” he says. “What we mean is that things come from plants and minerals, natural materials, and then go back to being natural materials . . . When you’re ‘regenerative,’ you add value back to the ecosystem, rather than being destructive.”

Liedtke says that 70% of clothing is created from “petroleum-based feedstock,” mostly various types of plastics, which never completely vanish or go away—they break down into microplastics and end up in the food and water supply. But his new clothing line does break down and go away; once you’re through with one of Unless’s garments, for instance, you can bury it in your backyard garden, and it’ll compost away. In an industrial composter, an Unless tee shirt will decompose within weeks.

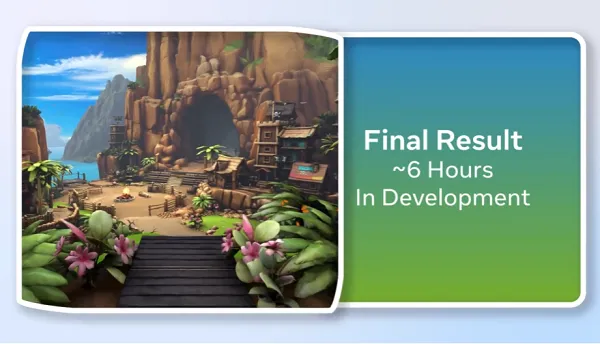

The new collection features shoes, jackets, vests, shirts, and more that are made from a variety of plant materials. For instance, shoe liners and soles are made from coconut husks and natural rubber latex, buttons are made from corozo nuts, Kapok cotton is used for insulation in vests and jackets, while cotton remains a staple for shirts and other garments.

Liedtke says that the garments are built to last, too, and could be compared to products from companies like Russell, Champion, Carhartt, or Dickies. And for those worried about their clothes decomposing while they sit in a dresser, he says not to worry: It takes very specific conditions to initiate the composting process—conditions hopefully not present in the typical closet or bedroom.

The collection is meant to be provocative, in some ways, and bring attention to the pollution that modern fashion and clothing manufacturing produces. In that way, it’s not too different from how companies like Beyond Meat and Impossible Meat disrupted the meat industry, or how EVs have shaken up the auto market in recent years.

Liedtke hopes that at least some clothing manufacturers will follow suit and start using more natural materials, rather than plastics, to cut down on waste and pollution. “The future is regenerative,” he says. “The question now is scaling it, and telling people about it.”

![How to Find Low-Competition Keywords with Semrush [Super Easy]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/73/62/7362f16fb9e460b6d58ccc09b4a048b6/how-to-find-low-competition-keywords-sm.png)