These diapers use plastic-eating fungi to biodegrade

When Johnson & Johnson launched the first disposable diaper in 1948, it revolutionized modern parenting. But it also, unwittingly, created an environmental disaster. Diapers are largely made of plastic, which does not biodegrade, but breaks into microplastics that pollute our waterways and end up in our food chain. And yet, more than 300,000 diapers are thrown out every minute, bound for landfills or incinerators, and accelerating climate change.[Photo: Hiro]There’s now a movement to design a more eco-friendly diaper, from creating easier-to-use cloth diapering systems to diapers that use less plastic. But Hiro, a newly launched startup, may have the most creative solution yet. It has launched a diaper that comes with a packet of plastic-eating fungi, which the company says will enable the diaper to biodegrade in the landfill.The startup is the brainchild of two serial entrepreneurs: Miki Agrawal, founder of Thinx period underwear and Tushy bidets, and Tero Isokauppila, founder of mushroom coffee brand Four Sigmatic. Agrawal has always been interested in tackling taboo issues, and when her son Hiro was born, she wanted to develop a diaper that was less harmful to the planet. That’s when she met Isokauppila, a Finnish entrepreneur who has devoted his entire career to making mushrooms more mainstream.[Photo: Hiro]A Fungi FanGrowing up, Isokauppila worked on the farm his family has tended since 1619. His work partly involved tending to mushrooms, which sparked a lifelong fascination with the plant. He went on to study fungi in college, learning about their powers as superfoods as well their ability to help other materials decompose. His knowledge of the a fungi’s nutrients to launch Four Sigmatic, which sells coffee that incorporates functional mushrooms.Now, Isokauppila is interested in how fungi can help us tackle the plastic crisis. Unlike other plants, mushrooms do not use photosynthesis to create energy. Instead, they need external food sources, and over the past 2.4 billion years they have existed, they have evolved to consume all kinds of materials. “In the earliest days of our planet’s existence, they ate rocks,” says Isokauppila. “When trees started growing, they evolved to consume trees, helping to transform them into fossil fuels.”About 15 years ago, a group of Yale undergraduates went to the Amazon and came across the first plastic-eating fungi. Plastic polymers are made of fossil fuels, and that’s a material that fungi has been interacting with for billions of years, according to Isokauppila. “My guess is that with so much plastic in our environment, fungi needed food, and plastic is fairly similar structurally to other materials it has consumed in the past,” says Isokauppila.[Photo: Hiro]The Plastic-Eating Hiro DiaperThere are now many scientists working on how to use fungi to process the enormous quantities of plastic in our environment, which accelerates the microplastics problem. In fact, there are already some solutions being developed. German scientists are trying to incorporate them into sewage treatment plants, while researchers from China and Pakistan identified plastic-eating fungi in a landfill in Islamabad. Even furniture companies are experimenting with additives that can help their plastic pieces degrade faster. Now Hiro is trying to use a strain of plastic-eating fungi in its diaper product.[Image: Hiro]Hiro diapers themselves are fairly typical. They have the same plastic content as other premium diapers and are made in a factory in Canada that produces diapers for other brands on the market. However, in the Hiro box, each diaper comes with a little packet of plastic-eating fungi that is dormant until it comes into contact with liquid. During changing time, you simply empty the whole pouch into the dirty diaper. This begins the process of biodegrading the plastic in the diaper. The company claims that within a year, the fungi in the diaper will completely consume the plastic.Isokauppila says that the goal is to incorporate the fungi directly into the Hiro diaper itself, to make the process more convenient. But when the company did focus groups with parents, they realized that they were very concerned about product safety, particularly since diapers make direct contact with the baby’s body. “Over time, we hope that with education, we show that the fungi is perfectly safe,” he says.Another question that comes up is whether the fungi is safe when released into the environment. Will it begin eating the plastic in trash bags or items in your environment that you don’t actually want to decompose? Isokauppila says that the decomposing process is slow, taking about a year. And once it is out in the wild—such as in the landfill—it will function much like other fungi in the environment. “They are already part of nature,” he says.[Photo: Hiro]Making Plastic-Eating Fungi WidespreadIsokauppila believes that the Hiro diaper can be a vehicle for popularizing plastic-eating fungi. As research begi

When Johnson & Johnson launched the first disposable diaper in 1948, it revolutionized modern parenting. But it also, unwittingly, created an environmental disaster.

Diapers are largely made of plastic, which does not biodegrade, but breaks into microplastics that pollute our waterways and end up in our food chain. And yet, more than 300,000 diapers are thrown out every minute, bound for landfills or incinerators, and accelerating climate change.

There’s now a movement to design a more eco-friendly diaper, from creating easier-to-use cloth diapering systems to diapers that use less plastic. But Hiro, a newly launched startup, may have the most creative solution yet. It has launched a diaper that comes with a packet of plastic-eating fungi, which the company says will enable the diaper to biodegrade in the landfill.

The startup is the brainchild of two serial entrepreneurs: Miki Agrawal, founder of Thinx period underwear and Tushy bidets, and Tero Isokauppila, founder of mushroom coffee brand Four Sigmatic. Agrawal has always been interested in tackling taboo issues, and when her son Hiro was born, she wanted to develop a diaper that was less harmful to the planet. That’s when she met Isokauppila, a Finnish entrepreneur who has devoted his entire career to making mushrooms more mainstream.

A Fungi Fan

Growing up, Isokauppila worked on the farm his family has tended since 1619. His work partly involved tending to mushrooms, which sparked a lifelong fascination with the plant. He went on to study fungi in college, learning about their powers as superfoods as well their ability to help other materials decompose. His knowledge of the a fungi’s nutrients to launch Four Sigmatic, which sells coffee that incorporates functional mushrooms.

Now, Isokauppila is interested in how fungi can help us tackle the plastic crisis. Unlike other plants, mushrooms do not use photosynthesis to create energy. Instead, they need external food sources, and over the past 2.4 billion years they have existed, they have evolved to consume all kinds of materials. “In the earliest days of our planet’s existence, they ate rocks,” says Isokauppila. “When trees started growing, they evolved to consume trees, helping to transform them into fossil fuels.”

About 15 years ago, a group of Yale undergraduates went to the Amazon and came across the first plastic-eating fungi. Plastic polymers are made of fossil fuels, and that’s a material that fungi has been interacting with for billions of years, according to Isokauppila. “My guess is that with so much plastic in our environment, fungi needed food, and plastic is fairly similar structurally to other materials it has consumed in the past,” says Isokauppila.

The Plastic-Eating Hiro Diaper

There are now many scientists working on how to use fungi to process the enormous quantities of plastic in our environment, which accelerates the microplastics problem. In fact, there are already some solutions being developed. German scientists are trying to incorporate them into sewage treatment plants, while researchers from China and Pakistan identified plastic-eating fungi in a landfill in Islamabad. Even furniture companies are experimenting with additives that can help their plastic pieces degrade faster. Now Hiro is trying to use a strain of plastic-eating fungi in its diaper product.

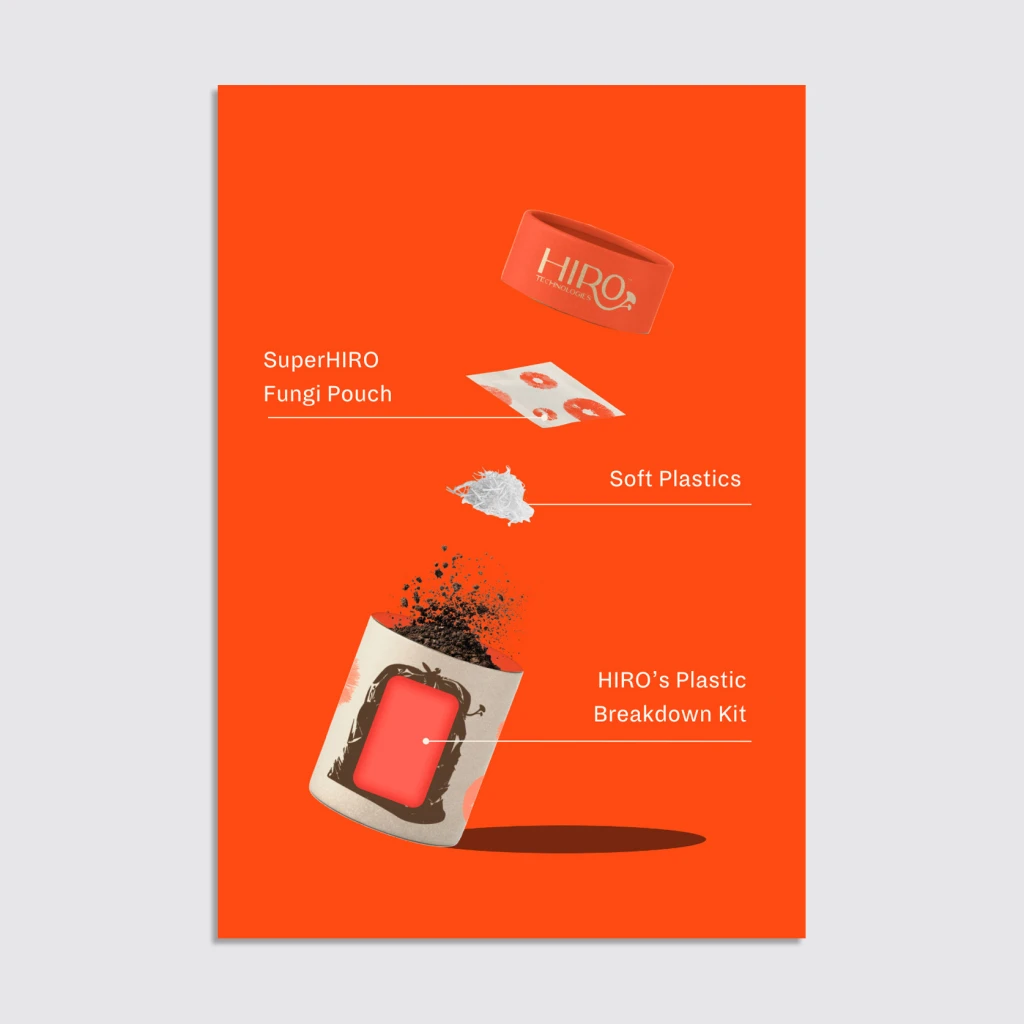

Hiro diapers themselves are fairly typical. They have the same plastic content as other premium diapers and are made in a factory in Canada that produces diapers for other brands on the market. However, in the Hiro box, each diaper comes with a little packet of plastic-eating fungi that is dormant until it comes into contact with liquid. During changing time, you simply empty the whole pouch into the dirty diaper. This begins the process of biodegrading the plastic in the diaper. The company claims that within a year, the fungi in the diaper will completely consume the plastic.

Isokauppila says that the goal is to incorporate the fungi directly into the Hiro diaper itself, to make the process more convenient. But when the company did focus groups with parents, they realized that they were very concerned about product safety, particularly since diapers make direct contact with the baby’s body. “Over time, we hope that with education, we show that the fungi is perfectly safe,” he says.

Another question that comes up is whether the fungi is safe when released into the environment. Will it begin eating the plastic in trash bags or items in your environment that you don’t actually want to decompose? Isokauppila says that the decomposing process is slow, taking about a year. And once it is out in the wild—such as in the landfill—it will function much like other fungi in the environment. “They are already part of nature,” he says.

Making Plastic-Eating Fungi Widespread

Isokauppila believes that the Hiro diaper can be a vehicle for popularizing plastic-eating fungi. As research begins to emerge around fungi that consume plastic, we will have more scalable solutions for tackling the enormous quantity of plastic that exists on our planet. But it is possible that consumers will find these solutions scary, partly because people in Western countries are just less familiar with mushrooms and fungi than in other parts of the world.

“In Asian culture and in Eastern Europe, people love mushrooms and have eaten them for thousands of years,” he says. “But in Anglo-Saxon cultures, there has been a fear of mushrooms, which is known as mycophobia.” (It isn’t clear exactly why; anthropologists suggest that it is because there is more mold in England because of the rainy weather, or because the church rejected the use of psychedelic mushrooms.)

Isokauppila wants to normalize the use of fungi to break down the plastics we use at home everyday. And over time, if we are able to scale the technology used in Hiro diapers, we could reverse the damage caused by our overuse of plastic.

While fungi do offer a glimmer of hope in our fight against the overwhelming plastic pollution problem, scientists say our goal should still be to cut down on our use of plastic. For one thing, we still don’t have a solution to breaking down plastic at scale. But there’s also the fact that when fungi does break down plastic, it releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, accelerating climate change.

Ultimately, our goal should be to avoid plastic entirely. But when that’s not possible—which is often—this is the next best solution. “If we can break down a diaper, we can break down anything,” he says. “Once we’ve gained enough market share, we can partner with other brands and bring this technology to the world.”

![31 Top Social Media Platforms in 2025 [+ Marketing Tips]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/0b/40/0b40fe7015c46ea017490203e239364a/most-popular-social-media-platforms.svg)

![[Weekly funding roundup April 12-18] VC inflow declines to 2nd lowest level for the year](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/220356402d6d11e9aa979329348d4c3e/WeeklyFundingRoundupNewLogo1-1739546168054.jpg)

![How to Find Low-Competition Keywords with Semrush [Super Easy]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/73/62/7362f16fb9e460b6d58ccc09b4a048b6/how-to-find-low-competition-keywords-sm.png)