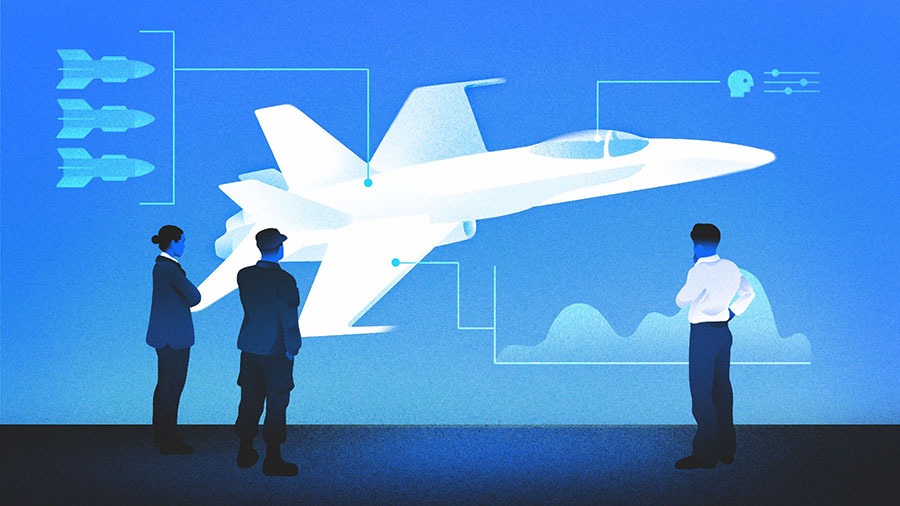

Silicon Valley has been trying to shake up defense contracting for years. With Trump, they have a willing audience

As defense startups proliferate, they look to the Pentagon for contracts—while encouraging it to reform itself.

- As Silicon Valley and Washington build closer ties, tech leaders offered advice on how the government can innovate better and faster. Founders and investors of defense tech startups said the Pentagon should cut down on lead times and raise its levels of risk tolerance in order to develop new weapons.

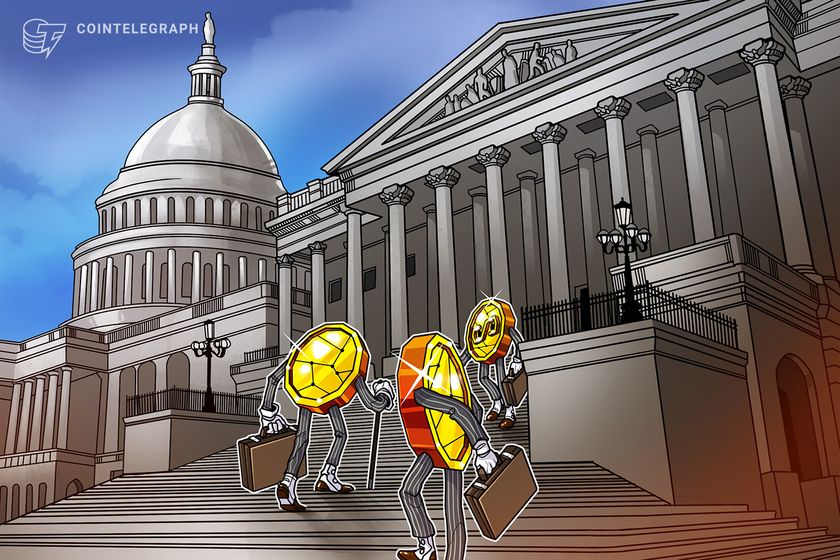

After years of trying to make inroads into the notoriously byzantine defense sector of the U.S. government, Silicon Valley is finally getting its chance.

A crop of new defense startups from the Valley are making their way to Washington at a time when the Pentagon is eager for new tech. Many leading figures from tech backed President Donald Trump’s reelection, cementing a new bond between an industry that had previously been known for supporting Democrats.

A recent conference in the nation's capital highlighted the new close ties between tech and government. The Hill and Valley Forum on Wednesday featured CEOs of top defense tech firms like Palantir’s Alex Karp and Anduril’s Brian Schimpf, rubbing shoulders with government officials like then-national security advisor Mike Waltz as well as members of the Senate Armed Services Committee such as Joni Ernst (R-Iowa), Mike Rounds (R-S.D.), and Jack Reed (D-R.I.).

Against the backdrop of the U.S.’s deepening geopolitical rivalry with China, the tech leaders’ entreaties for the government to take a page from its playbook found a welcome audience.

The White House is “absolutely dedicated to reforming the way we acquire technology” in order to modernize the U.S. military, Waltz said, a day before he left his role as national security adviser.

Trump signed several executive orders that would streamline how the Department of Defense acquires new defense systems. Defense tech startups had long maintained that current methods left them unable to compete with existing military contractors they viewed as having inferior products but deeper relationships at the Pentagon.

The executive orders are “going after things that always seem to cost too much, deliver too little and take too long,” Waltz told the audience during a panel titled The Arsenal Reimagined: Designing the DoD for the 21st Century Battlefield. “We can fill this auditorium with defense and acquisition reform think tank pieces, but you have a president and you have a leadership team that are all gas, no brakes, and sometimes we get to help them steer.”

At the center of the talks was the Pentagon’s inclination for long, extended bidding processes and research projects, and a risk-averse culture that made it harder for the DoD to take chances on experimental tech.

“There's a fundamental reality that innovation is messy and chaotic,” said Palantir chief technology officer Shyam Sankar.

On Friday, the White House submitted a 2026 federal budget that included $1.01 trillion in funding for the DoD. Defense tech startups find themselves in an odd position of both being frustrated with the DoD’s operations, which they view as stodgy and anti-meritocratic, and, at the same time courting its business. Now, given Silicon Valley’s close relationship with the Trump administration, it appears to have found the political allies for the reforms it seeks.

'You're still shooting uphill'

But even as the DoD opens up its procurement process to tech companies and startups, they will still face a difficult marketplace, according to Palantir's Karp.

“You're still shooting uphill, but shooting uphill and shooting like to Mount Everest while they're dropping grenades on you is a different story,” said Karp, whose company successfully sued the U.S. Army in 2016 for blocking it from bidding for a government contract. That move is widely considered to have opened the Pentagon’s doors to Silicon Valley.

Anduril's Schimpf suggested that the Pentagon should place large orders with defense startups. “If you buy things, capital will flow into defense,” he said. “Buy things at scale that matter, that move the needle and create opportunities to actually onboard.”

Without the guarantees of large contracts, Anduril has “just written off” developing new versions of products like air-to-air missiles it doesn’t believe will ever find a buyer, Schimpf added. “I don't think in 20 years anyone would buy any air-to-air missile we made, because they've already committed” to buying from someone else, he said.

Emil Michael, Trump’s nominee for undersecretary of defense for research and engineering, believes the Pentagon could be less reliant on tailor-made defense systems and more open to existing commercial products when looking for new tech to buy. “We don't need things that are always bespoke,” he said.

Michael, who is not yet confirmed for his role in the Pentagon, said the DoD could also benefit from looking at opportunities to save time, not just money. “Saving time is not something that's inherent in the DoD business model, [which is] about reducing risk to its smallest possible component at the expense of moving as fast as possible.”

Fail fast, fail often

In discussions about developing new technologies, the conversation often turned to one of Silicon Valley’s mantras: fail fast, fail often. The idea, which is a staple of tech culture, is that the many failed iterations of a product don’t matter so long as the final version works.

“Failure doesn't matter. It’s the magnitude of the success that matters,” said venture capitalist Vinod Khosla when asked about how to make the government more comfortable with risk-taking.

Palantir's Sankar suggested increasing competition between Defense Department employees to create, so they would have an “incentive to beat the bureaucrat two doors down the corridor.” He considers the DoD to be a monopsony that stifled innovation by being the only buyer of defense systems in the marketplace.

Instead, Sankar proposed having multiple program managers tasked with overseeing the same project, with the contract ultimately going to the one who delivered a better outcome. “They would wake up every day like hyper-competitive Americans trying to murder each other,” he said. “There would be an incentive like ‘yeah let's go faster. Let's do this better.’”

Speakers at the conference said the ongoing geopolitical tensions and AI arms race with China has only added more urgency to the issue.

“And when you're in an AI race when every innovation could lead to tens of billions, if not hundreds of billions, worth of value creation—and you think of value creation as a better defense, shield, more deterrence—every minute you're losing is costly,” said Michael.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com