Product, profit, returns: How Lightbox is looking to hand-pick its future portfolio companies

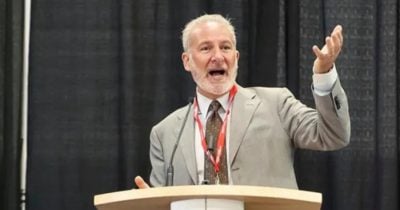

In an interview with YourStory, Lightbox’s partner and managing director, Sandeep Murthy, gives an inside look at its investment blueprint and what has worked for the firm.

The Indian startup ecosystem went from having 500 DPIIT-recognised startups in 2016 to nearly 1.6 lakh startups as of January 15, 2025. Amid the rising demand for capital, new and old venture capital firms are deploying India-focused funds to feed the new-age companies that are coming up today.

However, spoilt for choice, VC firms are increasingly focusing on one aspect while looking for their next big bet—product differentiation. According to Lightbox’s Managing Director and Partner, Sandeep Murthy, this is the company’s core focus while looking to write cheques.

Lightbox is no stranger to making risky bets—some, like Cleartrip and Info Edge, gave them successful exits, while others like Dunzo and WayCool have proven to be tougher.

But this is simply a part of a VC's role in the startup ecosystem. “To fund entrepreneurs, you have to be a little crazy,” Murthy says.

In an interview with YourStory, Murthy talks about how the firm is looking at the funding landscape, the need for core differentiation amongst startups, and its investment playbook as it prepares to launch its new fund.

Edited excerpts:

YourStory [YS]: Curious to hear how you're thinking about early-stage funding right now—are you seeing any ripple effects from what's happening in the later-stage market or the broader macro environment?

Sandeep Murthy [SM]: I’ve been in venture for about 20 years now, and the environment has definitely evolved—especially in India. In the early days, the excitement was all about building cutting-edge tech to change the world. But as the market matured, we started seeing global giants—Google, AWS, etc—really dominate the pure tech space. It’s tough to outdo them at their own game.

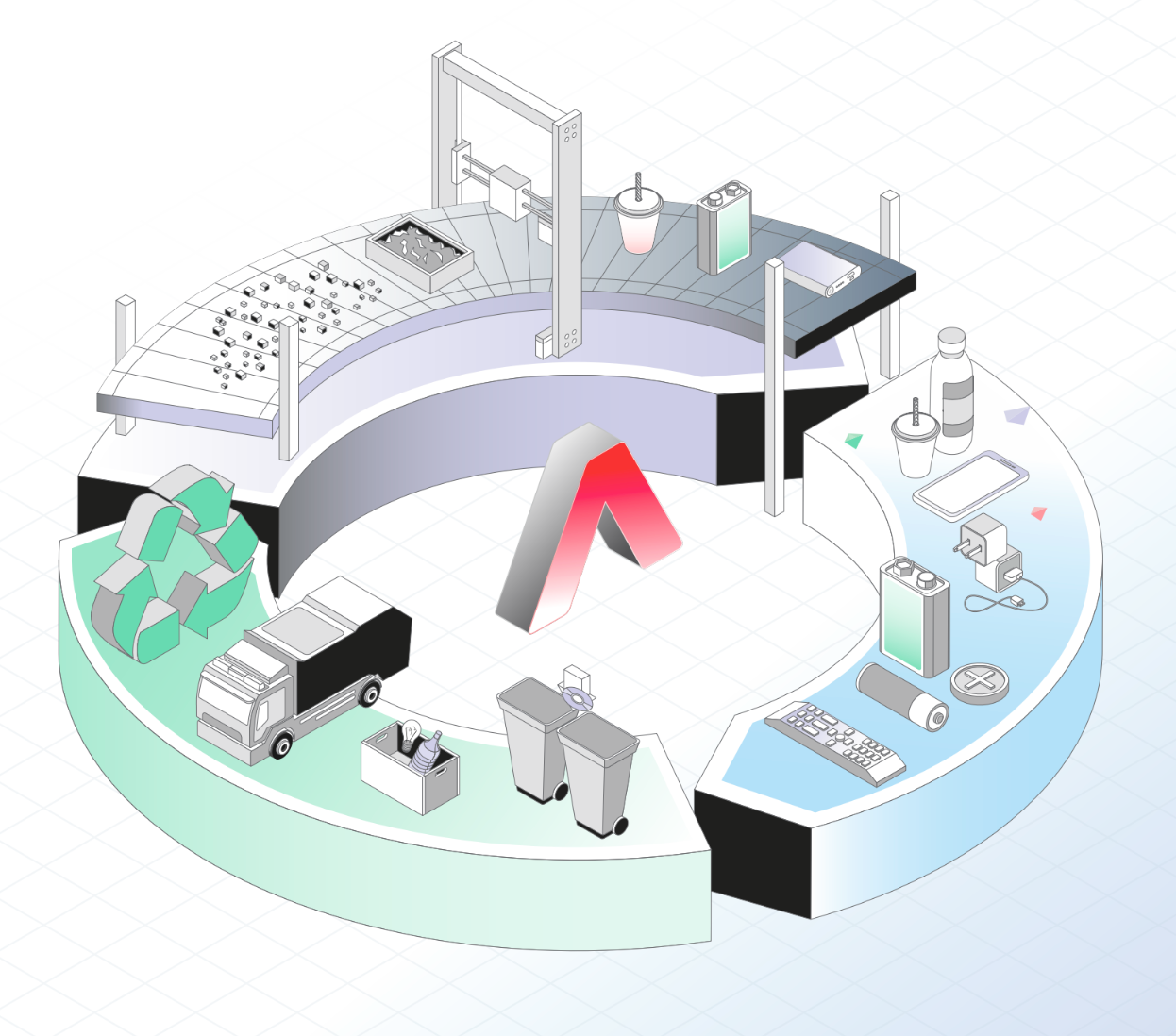

So increasingly, we’re drawn to businesses that have a strong local edge—especially in categories where production or supply chain can be a real differentiator. Take apparel, for example. The market’s super fragmented, and there’s room to build strong brands, but only if there’s something hard to replicate—like what The Bombay Shirt Company is doing with custom building at scale. We're looking for businesses where there's some operational moat or complexity that others can’t easily copy. That’s where we think the real value lies today.

YS: When it comes to retail and consumer-focused startups, how are you thinking about what it takes to build defensibility today—especially in a market where scale and differentiation are getting harder to crack?

SM: You have to think about retail a little differently today. Some startups—like in eyewear—have done a great job blending offline structure with online convenience. In our portfolio, Zeno’s doing that in pharmacies: organising offline stores but also enabling online engagement, with a focus on generics to help customers save. That required fixing the supply chain, which became a big differentiator.

More broadly, I think retail businesses need sharp, micro-market execution—start small, own a geography, and then expand. It’s not about scaling fast everywhere; it’s about winning locally first.

And product businesses? They need real operational moats. Like in furniture—designing, renting, refurbishing, managing logistics and capital—it’s all tough. But that’s the moat. Compare that to categories like mattresses, where the differentiation isn’t as clear, and you wonder how they’ll hold up when bigger players move in.

YS: Do you think early-stage founders today have a better grip on product-market fit given how much the ecosystem has matured, or are the core challenges still the same?

SM: I think calling the startup ecosystem 'mature' might be a stretch, because at its core, entrepreneurship requires a bit of madness. You have to believe in something the world hasn't seen yet, and as investors, we have to be a little crazy to back those visions. That spirit doesn’t really mature.

What does evolve, though, is experience. Founders today may have a sharper sense of what real differentiation looks like. Take Zeno—they started by fixing the broken supply chain for generics, knowing that true value comes from solving hard backend problems, not just chasing growth.

The ecosystem still gets carried away by sentiment. Whether it was the Alibaba IPO or now AI, hype cycles drive behaviour. But some founders are becoming more thoughtful. Nua, for example, hit profitability and resisted the urge to raise excess capital, despite someone offering way more than they asked for. That discipline, I’d say, is a positive shift.

Ultimately, there’s a difference between business rhythm and investor rhythm. If you’re forcing exponential growth onto a business that’s built for steady scaling, it creates unnecessary pressure. The smart ones today are building value first, then valuation.

YS: Early-stage deal activity seems to be picking up this year, but check sizes look smaller than before—have you noticed that trend too? And what's driving it?

SM: Yeah, I think it all comes down to sentiment. We're in a time of uncertainty, but also real opportunity. Funds have capital to deploy, but people are more cautious now—less wasteful. In a downturn, it actually costs less to acquire customers and hire talent, so it's a good time to build, just more deliberately.

Earlier, we saw big, almost irrational rounds—like fintechs raising $20 million at Series A. But now, there's a shift. Founders are realising capital isn’t the real differentiator—product is. We've had this habit of throwing money at problems, hoping to recreate China or the US. But methodical, disciplined building, like we’ve seen in some traditional public companies, can deliver venture-style returns too. So, smaller checks today reflect that more thoughtful approach.

YS: Any update on your $200 million fourth fund? When do you expect to start deploying capital?

SM: Fundraising is always a bit out of your hands—it happens when there's alignment and momentum. We're in conversations, and hopefully over the next 6–9 months, things will come together. But for now, we're focused on building the companies we already have.

We recently brought on an operating partner with deep experience to help our portfolio scale better. Raising a new fund is part of the journey, but it’s not the main thing—our real work is building value in the businesses we’ve already backed.

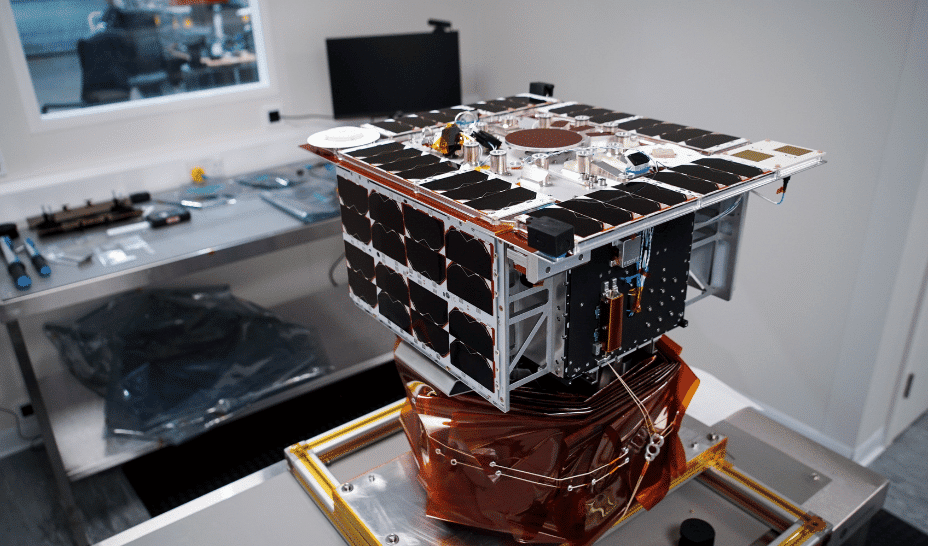

YS: Could you give us some insight into what your investment thesis would be for your next fund? How are you looking to provide liquidity to your limited partners (LPs)

SM: The next fund won't be about providing liquidity to our LPs; we’re exploring secondary vehicles or continuation funds for that. We’ve already sold part of our Rebel Foods position when Temasek and KKR invested, and we’re in talks with other secondary funds about providing liquidity.

As for new investments, that’s a separate journey—new capital for new opportunities. The two are largely uncorrelated, as secondary buyers focus on existing portfolios, while new investors are more interested in future prospects.

YS: How has the response been while raising your new fund—are you seeing more interest from domestic LPs now compared to earlier, when foreign capital largely dominated the ecosystem?

SM: Domestic capital has started coming in over the last few years, but I think there's still a learning curve. A lot of local investors come in thinking they'll make quick returns, but that’s just not how private markets work—you usually need to back at least two funds before you really see outcomes.

Foreign investors, on the other hand, have been doing this longer and are now looking for new growth markets since China’s become trickier. India is looking more attractive, but the big blocker is still liquidity—and that all comes down to profitability.

If companies can turn a profit, suddenly they have real options: go public, get acquired, or bring in bigger private equity. I think that’s the shift we’re going to see—more businesses focusing on profits so they can actually deliver returns, especially as global capital comes hunting for opportunity. Sandeep Agarwal, Founder, Droom

YS: You’ve had successful exits with companies like MapmyIndia and Info Edge. Can you share some insights into your current portfolio, particularly Rebel Foods and Droom, especially with their plans to potentially go public?

SM: Rebel (Foods), Droom, and Furlenco are all trending in the right direction. Rebel’s focus on unit economics and profitability is paying off, with impressive growth in safe kitchen sales. They’re well-capitalised and on track, but the IPO timeline is still uncertain.

For Droom, the pivot to mid-to-high-end vehicles and the addition of rental cars has improved their economics, and they’re eyeing a potential IPO by September. As for Furlenco, their furniture rental model is profitable, and they may go public to fund further growth.

The Bombay Shirt Company, too, is growing rapidly, with stores breaking even in just 1-1.5 months and paying back costs in about nine months. We're scaling from 20 to 45 stores by the end of the year, and that’s just the start. Liquidity for this company might take another year or two, but we’re excited about their trajectory.

YS: We've seen startups recently reducing their IPO sizes—do you think this is a response to current market conditions? What's driving that trend?

SM: I think companies are being more rational now. It’s no longer about grabbing as much money as the market will give. If you don’t have a clear use for the capital, there’s no point raising a huge amount—you can always raise more later. Given how many tech IPOs are trading below their listing price, founders are realising it’s smarter to start small, get a feel for public markets, and scale up if needed.

YS: From an investor’s perspective, how do you view this more cautious approach companies are taking while going public?

SM: I think companies are being smart by not chasing oversized IPOs or trying to sell a story that’s beyond what their business can deliver. The public markets aren’t as forgiving as private ones—if you take a lot of capital and underperform, investors won’t be pleased.

So instead, we’re seeing companies raise only what they need, showing discipline and balance. In a market where global sentiment is shaky, that’s the right call. As investors, we prefer that kind of rationality. We've seen what hype-driven fundraising can lead to—both in India and even in the US. Right now, we're in a more stable middle ground, and that’s a healthy place to be.

YS: You exited Dunzo in May last year. Given it was an early mover in hyperlocal delivery—a model now used by players like Zepto—what do you think went wrong? And what are your takeaways when looking at the quick commerce space today?

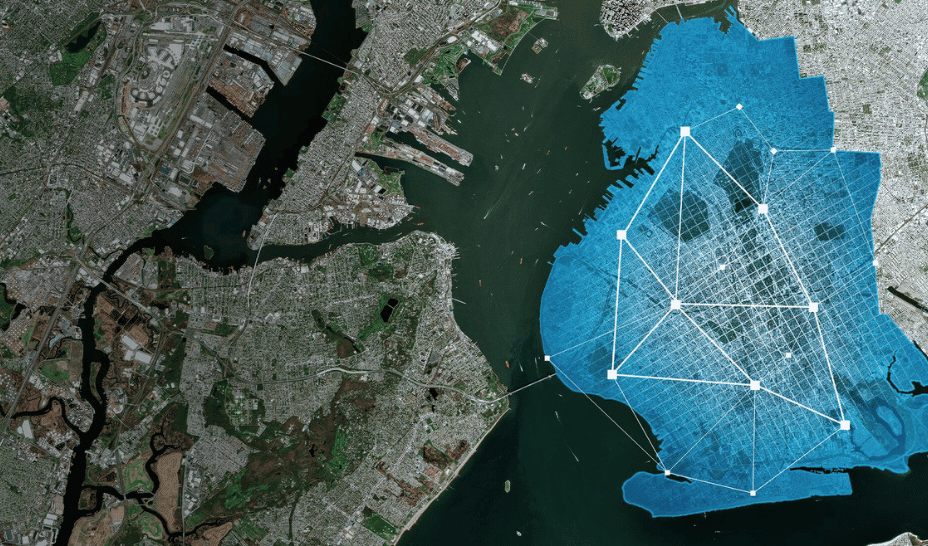

SM: Dunzo was a tough one. Being first doesn’t always guarantee success—just look at Friendster or the first auction sites before eBay. Dunzo had strong customer love, especially in Bengaluru, and low acquisition costs. But they lost focus on business fundamentals, particularly around unit economics and the cost structure of dark stores.

They got swept up in capital raising rather than building a sustainable retail model. And in a business like this, operational discipline is critical—Amazon is a perfect example.

Even now, I’m skeptical about the economics of quick commerce. The companies in this segment all seem to need constant capital infusions. That worries me. However, if it's tied into an existing infrastructure, like what Rebel is trying with 10-minute food delivery in Mumbai, it could work. Rebel already runs kitchens and owns strong brands like Faasos and Wendy’s, so they’re not building from scratch. Early signs from their pilot are promising—but measured.

YS: You've backed WayCool, and there have been reports suggesting they’re struggling with debt repayments. Is there any truth to that? And more broadly, are you seeing a slowdown in agri-tech funding?

SM: WayCool is facing some challenges, particularly with its debt, and it’s a tough situation. We’re working with both debt holders and equity shareholders to navigate it, but, unfortunately, it’s becoming more public than we'd like.

Agri-tech has also faced some unrealised potential. The concept is simple—reducing wastage in the agri-supply chain, like WayCool’s success in cutting down transportation waste from 33% to just 1%—but execution is tough. And that’s where a lot of players, including WayCool, have stumbled.

In entrepreneurship, you experiment, fail, learn, and repeat. Failures are part of the journey, and we’re working through these bumps with the hope of eventual success.

![An Ad Quality Control Checklist [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/6nIRujQEJFAZ7N9aiG3W8ZdvYsZHRQGEYXyTvI-9_h8/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9hZF9xdWFsaXR5X2NoZWNrbGlzdDIucG5n.webp)

![SWOT Analysis: What It Is & How to Do It [Examples + Template]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/86/6a/866a1270ca091a730ed538d5930e78c2/do-swot-analysis-sm.png)