How Ikea turned flat-pack furniture into a business worth billions

It doesn’t take long for Christer Collin and Ola Wihlborg to assemble the newest credenza from Ikea. Collin is a 42-year veteran of the company, specializing in product development. Wihlborg is one of the company’s most senior designers, having created dozens of pieces of furniture sold by the retailer since 2004. The two Swedes are lifting parts and turning hex wrenches in a second-floor conference room in Trnava, Slovakia, just outside the capital, Bratislava. This is where Inter Ikea Group (one of two Ikea parent companies) operates one of its more than 30 furniture and furnishings factories through its subsidiary, Ikea Industry, and where a sizable number of the retailer’s most commonly purchased items materialize.The credenza is one of Wihlborg’s own creations, and it has just come off the line of the sprawling factory downstairs. As he works, he’s barely consulting the detailed paper assembly manual familiar to anyone who’s put together a piece of Ikea furniture. “I can do it without, but it’s always nice to see the instructions,” Wihlborg says between sips of coffee, a model of Scandinavian cool in a black baseball cap and T-shirt. He has the design of the piece deeply ingrained in his brain after a three-year development process that’s brought it from concept to commercialization. Collin is an Ikea supply innovator whose job is to streamline how the company designs its furniture for customer assembly, and he’s visited dozens of Ikea factories and suppliers throughout his career. He can build with surgical precision. And because of the unique way Ikea has come to be such a dominant and global-scale furniture retailer, Wihlborg and Collin also know pretty much exactly how this credenza has been produced, down to the milling of the rails for its sliding doors and the location of the dowels that hold its sides in place.[Photo: Ikea]To a degree, most of Ikea’s 899 million annual customers probably don’t appreciate how the making of a piece of furniture like this credenza is a finely calibrated dance involving design, manufacturing, packaging, and assembly, with each element influencing the others in equal measure. Ikea’s designers must know how to make a piece of furniture, but also how it will be produced en masse, how it will end up on a shipping pallet, and how an untrained consumer can put it together without ripping their hair out.This interrelated process is the Ikea way, dating back to its world-changing leap into the self-assembled furniture business in 1952, and foundational to its global success. At the end of its 2024 fiscal year, Ikea parent company Ingka Group reported annual retail sales of 39.5 billion euro, or roughly $44.8 billion. Its share of the $940 billion global home furnishings market is a remarkable 5.7%. More than 727 million people visited its stores in 2024. It used about 473 million cubic feet of wood for its products, a figure that’s often compared to about 1% of the wood consumed around the world per year. As a company, it is an undeniable global force.It’s also been uncommonly influential in the business world. Though it did not invent flat-pack furniture, also known as knockdown furniture, it has so thoroughly saturated the market that all its biggest competitors, from Wayfair to Walmart, must do the same. Flat-pack furniture represents an $18 billion global market, a market many analysts expect to grow more than 50% over the next decade.Wihlborg and Collin have Ikea’s design-manufacturing-packaging-assembly calculus hardwired into their brains. Within 24 minutes of opening the credenza’s two boxes, they have the piece fully built. And though Wihlborg has run this design through his mind countless times over roughly three years of development—with concepts, prototypes, factory adjustments, revisions, and tiny tweaks—he had to come to this Slovakian factory to unbox and build the final product. “It’s actually my first time,” Wihlborg says, smiling.[Image: Ikea]Inside Ikea’s factoryEverywhere you look across the cavernous floor of Ikea Industry’s Trnava factory there is particleboard, often standing several feet high, and in hundreds and hundreds of stacks. Piled on racks that traverse the factory’s football-field-length halls on a network of rolling steel conveyors, these precisely processed cuts of particleboard come in a variety of densities and more than 20 different base dimensions. They get worked by hand, machine, and, increasingly, robot, to transform into the building blocks of some of Ikea’s best-selling shelves, tables, and chairs. Through a nearly scientific process, they’ve been refined to the size and form that simultaneously fit the intentions of the design concept, the capacities of the factory’s equipment, and the confines of a cardboard box a typical consumer can lift into the back of a car.The Trnava factory is one of Ikea’s flat-pack furniture powerhouses, running around the clock with 500 workers, three eight-hour shifts, and an active floor covering mo

It doesn’t take long for Christer Collin and Ola Wihlborg to assemble the newest credenza from Ikea. Collin is a 42-year veteran of the company, specializing in product development. Wihlborg is one of the company’s most senior designers, having created dozens of pieces of furniture sold by the retailer since 2004. The two Swedes are lifting parts and turning hex wrenches in a second-floor conference room in Trnava, Slovakia, just outside the capital, Bratislava. This is where Inter Ikea Group (one of two Ikea parent companies) operates one of its more than 30 furniture and furnishings factories through its subsidiary, Ikea Industry, and where a sizable number of the retailer’s most commonly purchased items materialize.

The credenza is one of Wihlborg’s own creations, and it has just come off the line of the sprawling factory downstairs. As he works, he’s barely consulting the detailed paper assembly manual familiar to anyone who’s put together a piece of Ikea furniture. “I can do it without, but it’s always nice to see the instructions,” Wihlborg says between sips of coffee, a model of Scandinavian cool in a black baseball cap and T-shirt. He has the design of the piece deeply ingrained in his brain after a three-year development process that’s brought it from concept to commercialization.

Collin is an Ikea supply innovator whose job is to streamline how the company designs its furniture for customer assembly, and he’s visited dozens of Ikea factories and suppliers throughout his career. He can build with surgical precision. And because of the unique way Ikea has come to be such a dominant and global-scale furniture retailer, Wihlborg and Collin also know pretty much exactly how this credenza has been produced, down to the milling of the rails for its sliding doors and the location of the dowels that hold its sides in place.

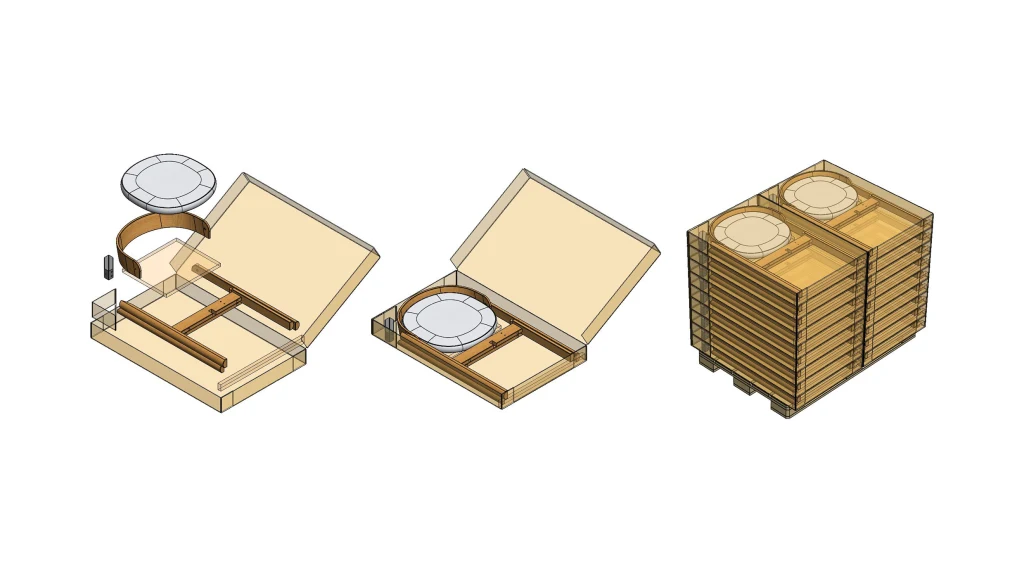

To a degree, most of Ikea’s 899 million annual customers probably don’t appreciate how the making of a piece of furniture like this credenza is a finely calibrated dance involving design, manufacturing, packaging, and assembly, with each element influencing the others in equal measure. Ikea’s designers must know how to make a piece of furniture, but also how it will be produced en masse, how it will end up on a shipping pallet, and how an untrained consumer can put it together without ripping their hair out.

This interrelated process is the Ikea way, dating back to its world-changing leap into the self-assembled furniture business in 1952, and foundational to its global success. At the end of its 2024 fiscal year, Ikea parent company Ingka Group reported annual retail sales of 39.5 billion euro, or roughly $44.8 billion. Its share of the $940 billion global home furnishings market is a remarkable 5.7%. More than 727 million people visited its stores in 2024. It used about 473 million cubic feet of wood for its products, a figure that’s often compared to about 1% of the wood consumed around the world per year. As a company, it is an undeniable global force.

It’s also been uncommonly influential in the business world. Though it did not invent flat-pack furniture, also known as knockdown furniture, it has so thoroughly saturated the market that all its biggest competitors, from Wayfair to Walmart, must do the same. Flat-pack furniture represents an $18 billion global market, a market many analysts expect to grow more than 50% over the next decade.

Wihlborg and Collin have Ikea’s design-manufacturing-packaging-assembly calculus hardwired into their brains. Within 24 minutes of opening the credenza’s two boxes, they have the piece fully built. And though Wihlborg has run this design through his mind countless times over roughly three years of development—with concepts, prototypes, factory adjustments, revisions, and tiny tweaks—he had to come to this Slovakian factory to unbox and build the final product. “It’s actually my first time,” Wihlborg says, smiling.

Inside Ikea’s factory

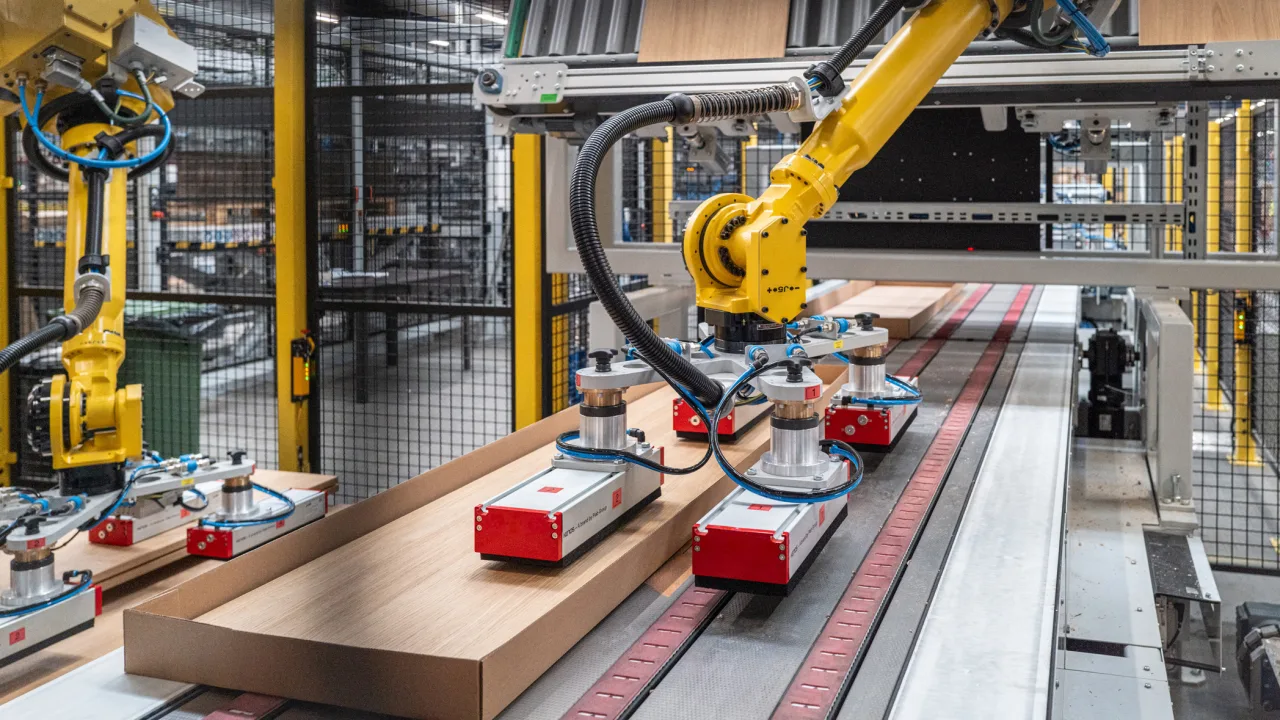

Everywhere you look across the cavernous floor of Ikea Industry’s Trnava factory there is particleboard, often standing several feet high, and in hundreds and hundreds of stacks. Piled on racks that traverse the factory’s football-field-length halls on a network of rolling steel conveyors, these precisely processed cuts of particleboard come in a variety of densities and more than 20 different base dimensions. They get worked by hand, machine, and, increasingly, robot, to transform into the building blocks of some of Ikea’s best-selling shelves, tables, and chairs. Through a nearly scientific process, they’ve been refined to the size and form that simultaneously fit the intentions of the design concept, the capacities of the factory’s equipment, and the confines of a cardboard box a typical consumer can lift into the back of a car.

The Trnava factory is one of Ikea’s flat-pack furniture powerhouses, running around the clock with 500 workers, three eight-hour shifts, and an active floor covering more than half a million square feet—twice the size of a typical Ikea store. It pumps out about 25,000 pieces of furniture every week. Its warehouses are stacked with assembly-ready boxes filled with Billy bookcases, Tonstad storage cabinets, and Hemnes bed frames.

Since October, the Trnava factory has also been producing about a dozen of the furniture pieces that make up Stockholm 2025, Ikea’s newest line of high-end furnishings, including Wihlborg’s credenza, which retails for $400. Its path through the factory—from raw particleboards to milled and veneered pieces to flat-packed final product—is a case study in the ways design, production, and packaging cross-pollinate to create the Ikea products that end up in homes all over the world.

It’s a process that starts with one of those stacks of particleboard. Workers in rubber gloves move wide rectangular boards onto a work surface, where one lays down a line of glue and the other mallets a strip of solid oak into a narrow slit. This piece will be the base of the credenza, and the length of solid wood will soon be sawed and milled with tiny channels for the credenza’s sliding doors—a higher-quality detail than the tacked-on plastic or aluminum rails that might be used in lower-cost products.

The credenza’s baseboard then heads off to another station, where a worker spends a full shift guiding close to 800 baseboards through a sanding machine that makes the glued oak piece exactly flush with the rest of the board. At the same time, a massive saw machine cuts down large sheets of particleboard to component size, before being automatically sorted and grouped for further processing.

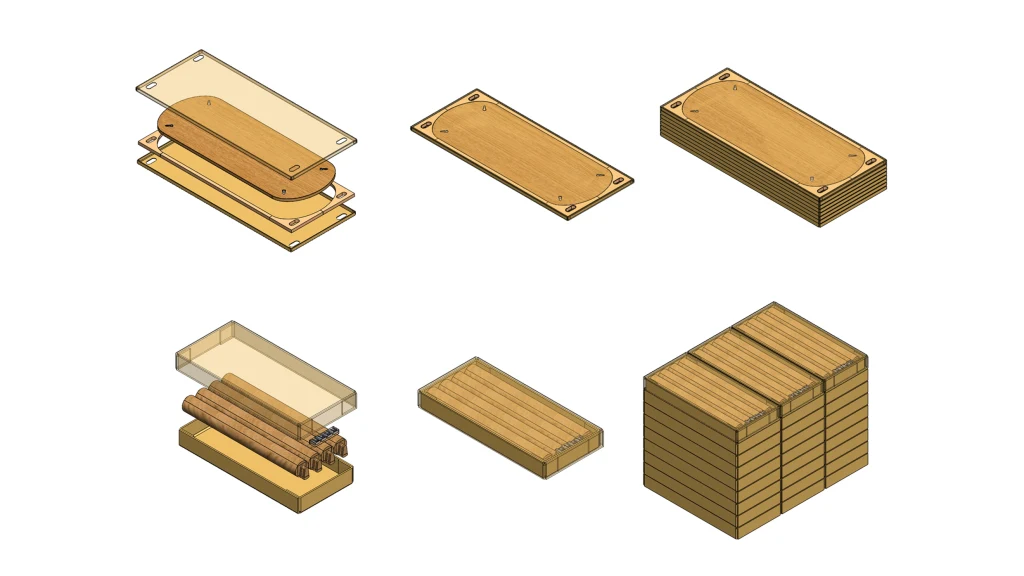

The sideboards, the interior shelves, the bottom supports, and the top all get cut and stacked and moved down the line. Pneumatic machines with grids of suction cups lift individual boards onto conveyor belts where they’re sprayed with glue, topped with wood veneer, and pushed into the hiss of a heated pressure machine. After seven seconds, they come out the other end with an aesthetically pleasing hardwood look, despite their cheaper and lighter particleboard innards. After edge shaving in one machine, another machine hot glues a strip of veneer around their perimeters, covering any hint of the base material inside.

These processes are being done in rapid, automated succession via complicated machines that are bigger than some people’s apartments. The Trnava factory has been chosen to produce this specific product because it has the capability of pulling off the higher-end details. This path through the factory line is one Ikea designers often follow from the earliest stages of their design development. They’ll tour Ikea-owned factories like this or the roughly 800 independent suppliers that produce the furniture, dishware, picture frames, and toilet cleaners that are sold in Ikea’s 481 stores in 63 global markets. What a given factory can make often helps shape a product’s design, and the design can push the factory to adopt new technologies and production methods.

A long shelf in the new Stockholm collection, also designed by Wihlborg, used a minimalist framing system that required extra strength in the fittings connecting the horizontal shelves to the uprights. Through a series of consultations, prototypes, and samples sent back and forth from Trnava to Ikea’s headquarters in Älmhult, Sweden, the design and factory teams landed on a unique, diagonally milled solution. “We very much appreciate these challenges,” says Marek Kováčik, site manager at the Trnava factory. “We never say no.”

The flat-pack formula

“It’s not only the product that has to be beautiful. The production has to be beautiful,” says Johan Ejdemo. As Ikea’s global head of design since 2022, he’s acutely concerned with the look, quality, and sales of the 1,500 to 2,000 new products that make their way into Ikea stores every year. As a trained cabinetmaker who’s spent years inside a carpentry shop, he’s also attuned to the realities of actually producing those products, and the compromises that sometimes have to be struck between design intention and material reality.

“There needs to be this rhythm. It’s almost like a dance. It has a certain tempo. It has a certain flow,” he says.

That dance is sometimes led more by a product’s design, at other times by the factory’s table saw tolerances, and at other times by the economics of cramming a coffee table’s parts into one box instead of two. Always, since the earliest days of Ikea as a furniture retailer, the end cost to consumers is the ultimate guide.

“First of all, we have the mission that we need to be smart with resources because we need to keep costs down. Because keeping costs down will enable a lower price, and the lower price will make more people able to afford it,” Ejdemo says. “It’s taking top-shelf things and moving them down a few steps so they’re easier to reach.”

This approach to what Ikea calls “democratic design” has been baked into the company’s DNA since it evolved from a provincial mail-order catalog in the 1940s to a home furnishings retailer by the mid-1950s. Its unique perspective on design, production, and packaging is all connected by the fundamental philosophy of self-assembly that has turned Ikea into a global behemoth.

Company lore has it that the light-bulb moment came around 1952 when Ikea founder Ingvar Kamprad and early Ikea employee Gillis Lundgren were wrapping up a photo shoot for a new Ikea catalog and they needed to move a bulky table. Lundgren noted how much simpler it would be to store the table if the legs could just come off. Kamprad realized that furniture would be so much easier (and cheaper) to sell through his mail-order business if it left the factory disassembled and as flat as possible.

In Leading by Design: The Ikea Story, a 1998 book coauthored by Swedish journalist Bertil Torekull, Kamprad writes that this became the basis for how the company approached all its products. Kamprad, who died at age 91 as a self-celebrated penny-pincher, summarized the Ikea way as “a design that was not just good, but also from the start adapted to machine production and thus cheap to produce. With a design of that kind, and the innovation of self-assembly, we could save a great deal of money in the factories and on transport, as well as keep down the price to the customer.”

Over the decades, this thinking has become inextricably connected to every stage of Ikea’s product development, which Ejdemo says has been helped along by better design tools, new factory technology, and innovative fittings to improve self assembly. Particleboard can be engineered to have higher density in the places where screws will make connections and lower densities elsewhere to bring down the total weight. An internally developed “wedge dowel” allows some parts to be snapped together without any screws.

The company has even adopted a technique from orthopedic medicine in which snap-together elements are ultrasonically welded into wooden pieces, forming a tight connection that allows parts to be assembled and disassembled repeatedly. Collin, who helped integrate this solution, says the company had been looking at ultrasonic welding for other purposes, but it ended up being a perfect way to integrate the hardware of a furniture piece. “The inside of a bone is quite similar to particleboard,” he says.

Operating at such a large scale in markets all over the world, Ikea’s product developers learn to internalize the interconnected nature of designing for the factory, the box, and the end user. Ejdemo, who started at Ikea in 1999 as a product engineer, says designers come to have three numbers in their minds at all times: the 80-centimeter width and 120-centimeter length of the shipping pallets that carry boxed products from factory to store, and the 25-kilogram weight limit (about 55 pounds) the company has for those boxes.

Some might call this a curb on creativity, but Ejdemo sees it pragmatically. “I need to consider this because it will be considered anyway at some point,” he says. “If you’re not on top of it as a designer you might see things happening that you wouldn’t want to happen from a design perspective.”

Achieving massive scale

Walking through the Trnava factory’s vast halls, production manager Michal Puškel bends down periodically to pick up a stray piece of packing tape or paper from the floor. The factory is impeccably clean, despite stacks of particleboard snailing their way across acres’ worth of conveyors, and high-speed saws, mills, and drills cutting through boards by the thousands. The factory has been operating here since 1990, back when this was still Czechoslovakia and Ikea was making inroads into formerly communist countries.

Over the years, the Trnava factory has been thoroughly modernized, with long chains of automated machines and a growing number of robotic arms deployed throughout. Puškel seems to know each machine just as well as the many workers he stops to chat with on his way down the production line, highlighting their unique capabilities and stepping over components to point out the best view.

At the end of one machine’s conveyor, he leans over a rail and pulls off a processed board, one of the bigger parts of the credenza the factory is currently producing by the hundreds per day. With his finger he touches the places where, within seconds, the machine has milled small notches where other pieces will soon be attached, and it’s also drilled the precise holes that customers will use to complete the final assembly—the sweat equity that keeps Ikea prices low.

The Trnava factory specializes in this type of particleboard and veneer manufacturing, known as flat-line production, where each piece moves down the line and slowly gets turned into a more refined part of a piece of flat-pack furniture. But some items require more attention to detail, including several of the pieces the factory is making for the new Stockholm line.

One is the long shelving unit Wihlborg designed after a lengthy back-and-forth with the factory over how to connect its shelves to its upright supports. The solution they came up with—a somewhat complex hole milled at a 45-degree angle into the upright supports in order to conceal the hardware in the finished piece and maintain strength—requires each shelf and upright to get processed by a massive computer numerical control (CNC) milling machine. Crossing the factory to a bright and noisy corner, Puškel shows off a cluster of CNC machines that can take each of those shelving unit’s pieces and mill the angled hole, perform multiple cuts using a menacing multiblade saw arm, and smooth out the radii to ensure the pieces come together snugly.

Nearby, a worker has a recently milled board up on a table with a measuring tape, and he’s consulting a diagram as he checks the size of each hole and groove. “We inspect every hour,” Puškel says, with his own eye on the inspector. Other parts of the factory have a visual system to check for less-intricate mistakes, like chipped corners or misaligned veneers; if it sees a problem five times in a row, it automatically shuts down the line.

Mistakes happen, and Puškel says it’s critical to keep a close watch on the line any time it starts up on a new batch of one of the hundreds of furniture types the factory produces. But it doesn’t take long for the factory to find its groove. “After a half hour, everything will be stable,” Puškel says. Then it will be ready to keep pace with Ikea’s massive globe-spanning scale.

The big business of logistics

Ikea has a business imperative to pay so much attention to the intricacies of how every piece of furniture is designed, made, and packaged. Craig Martin, a professor of design at the University of Edinburgh, has written extensively about mobility and design, from shipping containers to the cardboard blocks used to fill empty space in Ikea furniture boxes. He says Ikea is uniquely concerned with these mundane details. “In the traditional design process, packaging is a bit of an afterthought. With Ikea, packaging design and logistics were very much part of that same developmental process. I think that’s one of the most interesting things about Ikea,” Martin says. “I’m not aware of many other manufacturers or companies who are so invested in logistics the way Ikea is.”

The reasoning behind it is cost, Martin says, which has been key to Ikea’s ability to gain such a large share of the furniture market. “It’s about the economics of it. If you can save money by building logistics and packaging design into the design process, then that’s the crux,” he says.

As a company with tens of thousands of employees worldwide, Ikea has plenty of specialists who make sure packaging is optimized and logistics are efficient. But these concerns have also trickled down throughout the design and product development pipeline, and designers like Wihlborg can conceptualize their design as both a built and a flat-packed product. “During the process, of course we think about how to knock down the product and pack it in a flat pack, so we don’t go into something that is impossible,” Wihlborg says. “We always have it in mind.”

Flat-packing concerns shape decisions far beyond the look or size of individual items. Karin Gustavsson, creative leader for the Stockholm 2025 collection, says the close collaboration between designers and factories helps ensure these efficiencies are identified as early as possible. “If you see that it helps to make the table 10 centimeters smaller in length, then we need to start over to do new samples and try it and ask is it okay to just shrink it in length or should we change anything else,” she says. “All this is in the design process.”

These considerations end up playing a surprisingly large role in determining the design of Ikea’s products. For example, the dining table Wihlborg designed for the Stockholm 2025 collection used one density of wood where its legs attach, a lower-density around the perimeter, and a nearly hollow but structurally sound honeycomb-shaped cardboard filler for the center—an approach that reduced its overall weight while reducing its risk of bending. It also meant the tabletop wouldn’t need a supporting frame underneath, cutting material use, the total number of boxes the product fits in, the overall cost to customers, and the carbon emissions required to ship it. “Those things we can simulate very easily with computerized design,” Gustavsson says.

Some have criticized Ikea for optimizing its design for cost, arguing it creates a kind of disposable furniture that sacrifices durability for rock-bottom prices. The Lack side table, now retailing for $12.99, is one common scapegoat. It is also a perennial bestseller. With thousands of products on offer, Ikea’s range of quality is inevitably going to be wide, but Gustavsson says the company is trying to prove that it can hit new heights in quality without getting too far out of the common person’s price range. “We don’t believe in fast fashion always. We’ve tried to make Stockholm very high quality and long lasting. It has been the mantra for us to show that Ikea could really be this high-end furniture,” Gustavsson says. “We’ll also attract a new customer, we believe.”

The company is also trying to counter the disposable-furniture criticism by prioritizing design for both assembly and disassembly, allowing customers to more easily pack up a piece of Ikea furniture and move it to a new place instead of leaving it on the curb. Collin, who was part of the team that developed the snap-in-place wedge dowel, says the move is toward “enjoyable assembly,” and new fittings and assembly techniques are part of making that possible.

He points to studies the company does of people’s expectations of how long it will take them to build a given item. “With the old fittings”—think screws and hex wrenches—“it always took double what they expected,” Collin says. Now, with pieces that snap boards together instead of chip-prone nailings or patience-draining hex screws, more and more products have milled wedge dowels that snap and lock into place and easily placed plastic fittings that hold a bookcase backing tight without a single nail.

“We always try to be better and better on assemblies. You should feel like you made it in the time you expected,” Collin says. If a product is easier to build, he says, it should be easier to take apart as well.

This thinking is making its way across Ikea’s design portfolio, according to Ejdemo. “The whole system change toward circularity will demand a lot of us. How will things be packed and distributed and how will you be able to resell, repair, give a second life, upgrade, update,” he says. “There’s more involved in this than the products, but it will require shifts and new thinking into the products to enable that to happen.”

Near the end of the production line inside the Trnava factory, the 16 individual wooden pieces of the credenza are all processed and finished, with their uniform oak veneers and precisely aligned dowel and screw holes. They’ve been wheeled or forklifted over from various parts of the factory to the flat-packing area, which has become one of the busiest and most dynamic parts of the facility.

Here Kováčik, the site manager, points out the facility’s newest pieces of equipment: a set of five-axis robotic arms that are currently being programmed to perform the Tetris-like job of fitting every part of an Ikea product into a tightly packed box—and in the right order. “It’s done in consecutive steps, according to the assembly instructions,” Kováčik says.

The new robots are doing the heavy lifting, grabbing the largest pieces of the credenza and laying them inside the bottom of a box another machine has just finished folding and gluing. Down the line, two human workers neatly place a few of the smaller wooden pieces in the box before it moves on to another group of workers who lay down other parts of the credenza. Each one goes in a specific place, with the narrow gaps of negative space filled in with strips of thick cardboard, placed down by hand. By the time each worker has laid their pieces in the box, another is coming toward them on the conveyor belt.

Puškel, the production manager, says the robots will eventually be able to plop in even the smaller parts of a furniture item, reducing the need for workers to stand by and place parts in boxes over and over again. He lists out the downsides of such rote human labor: ergonomic risks that can hurt workers, worker sick days that can hurt productivity, and human salaries that hurt the bottom line. Kováčik assures that any work a robot takes over simply creates opportunity for human workers to do something more worthwhile.

One job no robot will soon take over is the designated assembly inspector, who spends their shift picking out 10 to 12 finished furniture pieces from the assembly line, opening their boxes, and putting them together, like an Ikea customer outfitting a new apartment.

On this day, the inspector on duty takes a little more than 10 minutes to mostly build the credenza, looking for the main issues of chipped corners and mismatched veneer colors. Once it’s passed, the inspector takes the pieces apart and places them neatly back in their boxes to join the rest of the day’s output. Stacks of these boxes make their way to another set of robots that carefully arrange them on pallets that will be shipped around the world and placed in the warehouse-like “self-serve” sections of Ikea stores. One last refrigerator-size machine reaches out a robot arm and slaps the palletized boxes with identifying labels. “Now,” Puškel says, with a nod, “it’s finished.”

A long-term relationship

Back in the factory’s second-floor conference room, Collin is sitting on the credenza he and Wihlborg have just assembled. “I’m not the heaviest TV,” he says. His point is that this is a piece of furniture that’s meant to perform, withstanding all the reasonable and sometimes unreasonable conditions it will be thrust into when it ends up in a living room in Tulsa, Oklahoma, or Guangzhou, China.

For all the ways Ikea furniture is designed for the back end—for the company’s design intentions, for the supply chain and production process, for the complex logistics of global domination—it is, ultimately, something that will live in people’s houses for years or decades. The way the furniture is designed, produced, and shipped is interconnected in an increasingly complex way. But the goal remains quite simple: to create furniture that people will use.

![31 Top Social Media Platforms in 2025 [+ Marketing Tips]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/0b/40/0b40fe7015c46ea017490203e239364a/most-popular-social-media-platforms.svg)

![[Webinar] AI Is Already Inside Your SaaS Stack — Learn How to Prevent the Next Silent Breach](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiOWn65wd33dg2uO99NrtKbpYLfcepwOLidQDMls0HXKlA91k6HURluRA4WXgJRAZldEe1VReMQZyyYt1PgnoAn5JPpILsWlXIzmrBSs_TBoyPwO7hZrWouBg2-O3mdeoeSGY-l9_bsZB7vbpKjTSvG93zNytjxgTaMPqo9iq9Z5pGa05CJOs9uXpwHFT4/s1600/ai-cyber.jpg?#)

![How to Find Low-Competition Keywords with Semrush [Super Easy]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/73/62/7362f16fb9e460b6d58ccc09b4a048b6/how-to-find-low-competition-keywords-sm.png)