A Vanishing $212M Bitcoin Order Caused Chaos for Traders. Is Spoofing Back in Crypto?

Despite increased scrutiny, spoofing remains a challenge in crypto, highlighting the need for better surveillance and stricter regulations.

On April 14, someone put in a sell order for 2,500 bitcoin, worth roughly $212 million, on the Binance order book at $85,600, around 2-3% above the spot prices trading at the time.

Seeing such a large order, the bitcoin price started to gravitate to this level at around 17:00 UTC.

Suddenly, the order was gone, as seen using Coin Glass data, which caused a brief moment of market apathy as bulls and bears tussled to fill a void in liquidity.

The bitcoin price at the time, however, was already on shaky ground due to geopolitical concerns. Subsequently, it went lower after the vanishing order caused chaos for the traders.

So what happened?

One answer could be an illegal technique that involves placing a large limit order to rile trading activity and then removing the order once the price comes close to filling it. This is called "order spoofing," defined by the 2010 U.S. Dodd-Frank Act as "the illegal practice of bidding or offering with the intent to cancel before execution."

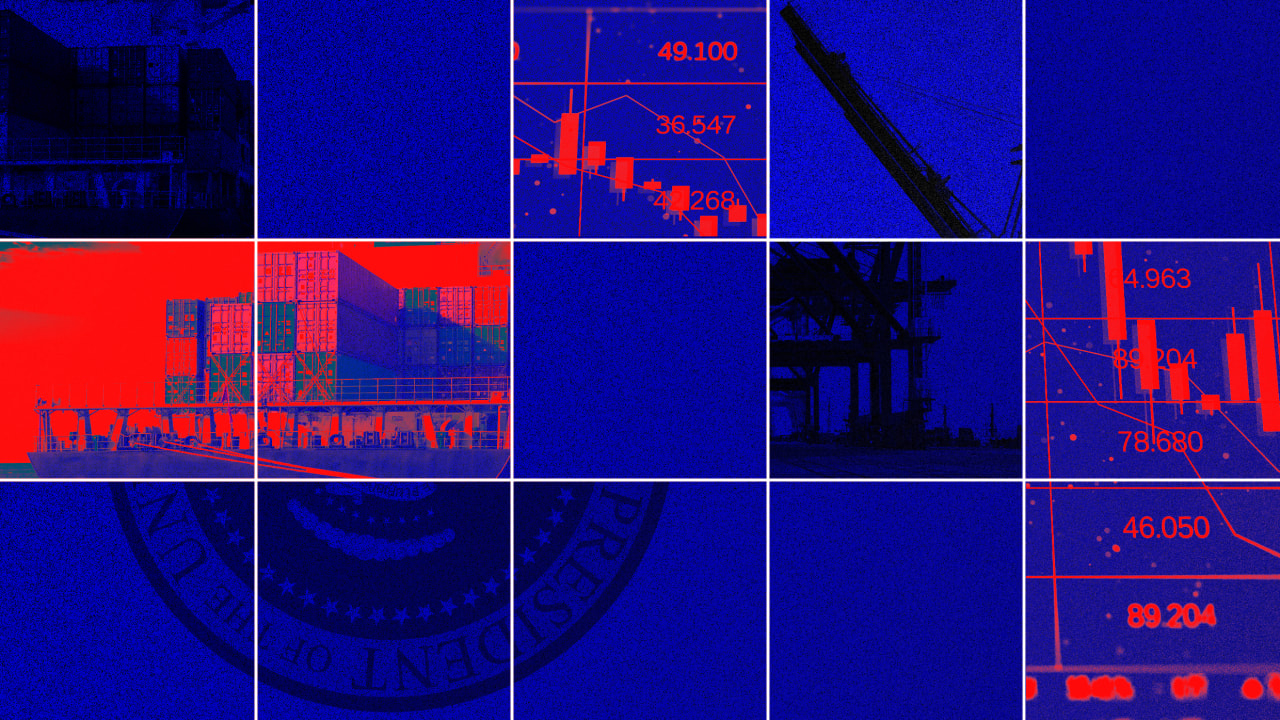

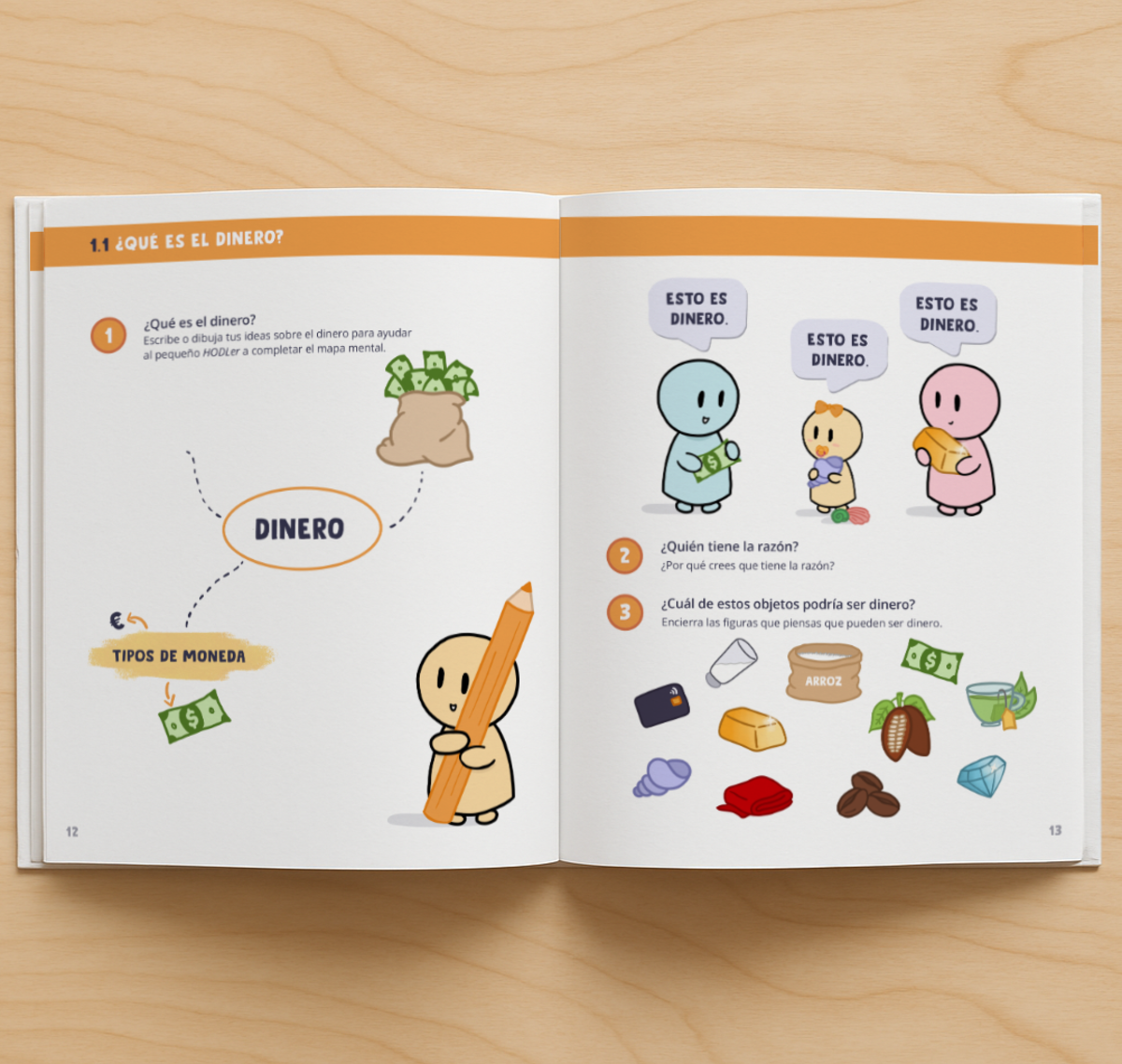

As seen in the liquidity heatmap in the image above, on the surface, the order with a price of $85,600 seemed like a key area of resistance, which is why market prices started to gravitate towards it. However, in reality, that order and liquidity were likely spoofed, giving traders the illusion of a stronger market.

Liquidity heatmaps visualize an order book on an exchange and show how much of an asset rests on the book at each price point. Traders will use a heatmap to identify areas of support and resistance or even to target and squeeze under-pressure positions.

In this particular case, the trader seemed to have placed a possible spoof order when the U.S. equity market was closed, usually a time period of low liquidity for the 24/7 bitcoin market. The order was then removed when the U.S. market opened as the price moved towards filling it. This could still have had the desired effect, as, for instance, a large order on one exchange might spur traders or algorithms on another exchange to remove their order, creating a void in liquidity and subsequent volatility.

Another reason could be that the trader placing a $212 million sell order on Binance wanted to create short-term sell pressure to get filled on limit buys, and then they removed that order once those buys were filled.

Both options are plausible, albeit still illegal.

'Systemic Vulnerability'

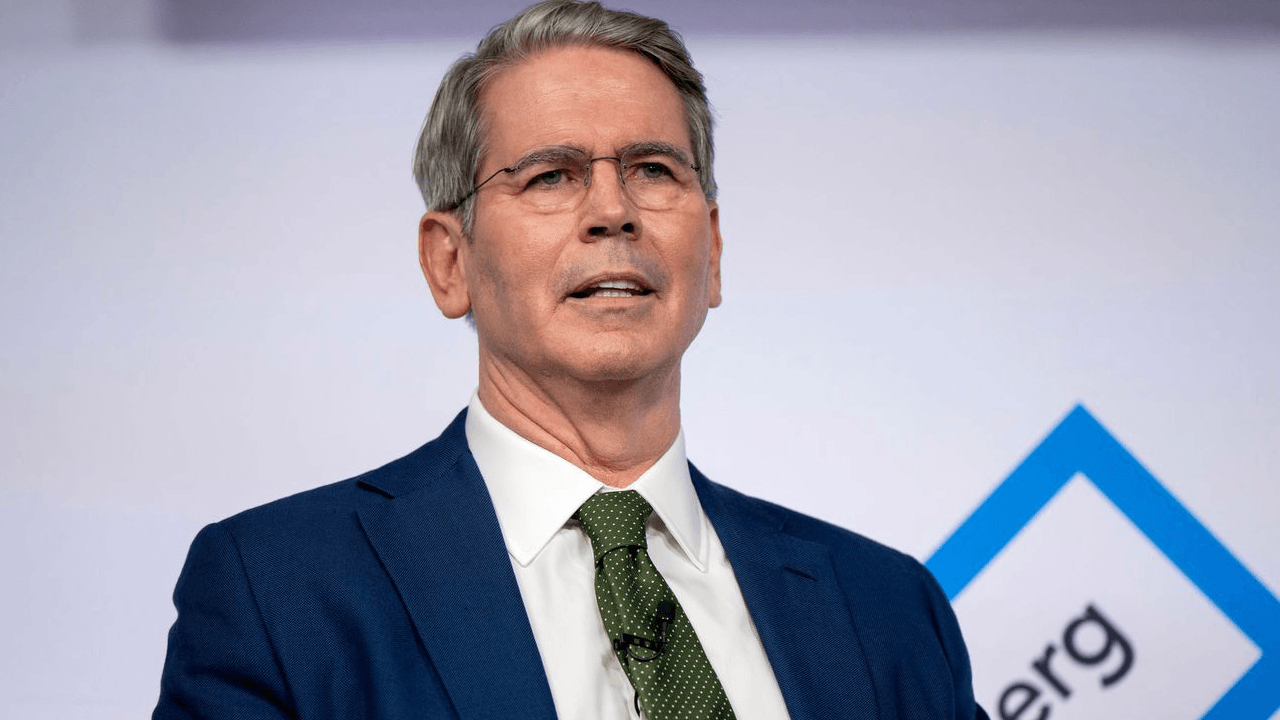

Former ECB analyst and current managing director of Oak Security, Dr. Jan Philipp, told CoinDesk that manipulative trading behavior is a "systemic vulnerability, especially in thin, unregulated markets."

"These tactics give sophisticated actors a consistent edge over retail traders. And unlike TradFi, where spoofing is explicitly illegal and monitored, crypto exists in a gray zone."

He added that "spoofing needs to be taken seriously as a threat as it helped trigger the 2010 Flash Crash in traditional markets, which erased almost $1 trillion in market value."

Binance, meanwhile, insists that it is playing its part in preventing market manipulation.

"Maintaining a fair and orderly trading environment is our top priority and we invest in internal and external surveillance tools that continuously monitor trading in real-time, flagging inconsistencies or patterns that deviate from normal market behavior," a Binance spokesperson told CoinDesk, without directly addressing the case of the vanishing $212 million order.

The spokesperson added that if anyone is found manipulating markets, it will freeze accounts, report suspicious activity to regulators, or remove bad actors from its platform.

Crypto and spoofing

Spoofing, or a strategy that mimics a fake order, is illegal, but for a young industry such as crypto, history is rife with such examples.

During 2014, when there was little to no regulatory oversight, the majority of trading volume took place on bitcoin-only exchanges from retail traders and cypherpunks, opening the industry to such practices.

During 2017's ICO phase, when trading volume skyrocketed, tactics such as spoofing were also expected, as institutions were still skeptical about the asset class. In 2017 and 2018, traders regularly placed nine-figure positions that they had no intention of filling, only to pull the order shortly after.

BitMEX founder Arthur Hayes said in a 2017 blog post that he "found it incredible" that spoofing was illegal. He argued that if a smart trader wanted to buy $1 billion of BTC, they would bluff a $1 billion sell order to get it filled.

However, since the 2021 bull market, the crypto market has experienced waves of institutional adoption, such as Coinbase (COIN) going public, Strategy (formerly MicroStrategy) going all-in on bitcoin, and BlackRock launching exchange-traded funds (ETFs).

At the time of writing, there are no such large orders that indicate further spoofing attempts, and spoofing attempts have seemed to have become less blatant. However, even with billions traded by TradFi firms, examples of such a strategy still exist across many crypto exchanges, particularly on low-liquidity altcoins.

For example, last month, cryptocurrency exchange MEXC announced that it had reined in a rise in market manipulation. An internal investigation found a 60% increase in market manipulation attempts from Q4 of 2024 to this first quarter of this year.

In February, a trader manipulated the HyperLiquid JELLY market by tricking a pricing oracle, and HyperLiquid's response to the activity was met with skepticism and a subsequent outflow of capital.

How does the crypto market combat spoofing?

The burden ultimately lies with the exchanges and regulators.

"Regulators should set the baseline," Dr. Jan Philipp told CoinDesk." [Regulators] should define what counts as manipulation, specify penalties and outline how platforms must respond."

The regulators have certainly tried to clamp down on such schemes. In 2020, rogue trader Avi Eisenberg was found guilty of manipulating decentralized exchange Mango Markets in 2022, but the cases have been few and far between.

However, crypto exchanges must also "step up their surveillance systems" and use circuit breakers while employing stricter listing requirements to clamp down on market manipulation, Philipp said.

"Retail users won't stick around if they keep getting front-run, spoofed and dumped on. If crypto wants to outgrow its casino phase, we need infrastructure that rewards fair participation, not insider games," Philipp concluded.

![Experts Don’t Believe AI Tools Will Lead to Mass Job Losses [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/gcXE1_Da13Oz-JAszjUwb6v5UqMp2MFMjDAIXPbLad0/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9haV9qb2JfbG9zc2VzLnBuZw==.webp)